Funny Like a Clown

Every year, silent film lovers flock towards a small Italian town to get their cinephile kicks, and this year was no different. Anyone who has ever pondered whether good old-fashioned pizza would taste better after good old-fashioned movies should have been at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto – or ‘The Days of Silent Film’ – in Pordenone between the 4th and the 11th of October, where musings like these were never more valid. The 27th Pordenone Silent Film Festival (as it is alternatively titled) was a wonderful amalgam of themes varying from early Russian animation, by the hand of ballet dancer Alexander Shiryaev, to the silent comic works of W.C. Fields, with lots of exclusive footage in between. A program filled to the brim like this one went hand in hand with a few eye openers, and for me, a clown was one of them.

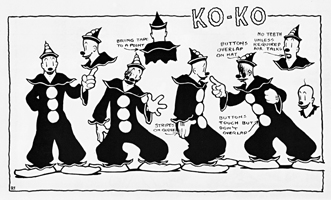

That clown is now known as Ko-Ko, and the animated short film in question was Modeling by Dave Fleischer, a Max and Dave Fleischer production from 1921. The Fleischer brothers were a creative duo responsible for such animation heavyweights as Betty Boop, Popeye the Sailor and Superman, and produced and directed over 600 shorts together – Max was usually given the producing credit, and Dave the directing credit. It was the eldest brother Max, however, who got the animated ball rolling. Around 1901, Max was working at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle as a “cub artist, retouching photographs,” and had a first encounter with future animation pioneer John Randolph Bray, who was working at the art department (Barrier 22). Both gentlemen were cartoonists who were interested in animation, and it was through J.R. Bray that Max Fleischer officially entered the animation business.

(Modelling can be viewed here.)

John Randolph Bray managed to sign a contract with the French company that ruled the roost at the outset of French cinematic history, and took America by storm in the nickelodeon era, namely Pathé Frères (Abel 24-29). The first film he released through Pathé was The Artist’s Dreams or The Dachshund and the Sausage (J.R. Bray, 1913), which was partly produced under his own studio heading, J.R. Bray Studios. Bray hired an entire team of talented artists to work on his short films, and effectively streamlined the animation process by improving the available technology and compartmentalizing the animation work – the latter was a precursor to the classical Hollywood mode of production. His partnership with Pathé saw the birth of Colonel Heeza Liar, whose popularity made him one of the first serial animated cartoon characters. The Colonel went on to appear in 59 episodes from 1913 to 1924.

The creative impetus and historic importance of J.R. Bray was combined in his patents, one of which revolutionized animation. Together with another animation great by the name of Earl Hurd, Bray developed cel animation, a process patented by both and combined in a joint venture called the Bray-Hurd Process Company in 1917 (yet already patented in 1915). Cel animation entails the use of transparent celluloid sheets – hence ‘cel’ – on which certain elements are drawn, and then several sheets are composited (i.e. layered on one another) and shot to form one image, so that non-moving elements – such as backgrounds – did not have to be ‘reanimated’ from scratch every time. Before this innovation, artists, like Winsor McCay, would redraw everything, or use the self-explanatory ‘slash and tear’ system invented by Raoul Barré. Needless to say, cel animation became the standard, for it shortened production time and increased the possibilities of animators. The Bray-Hurd Process Company managed to keep their patents until they expired in 1932, having thus earned a fortune selling cel animation licenses. The combination of this technique and Bray’s factory-like approach to animation – before his creative team approach, animation was the sole work of the artist – was the key to his success, and a precursor to most of the animation studios that would follow.

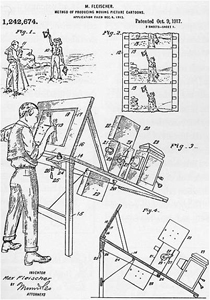

The reason I go into these technicalities, is because they shed important light on the progress of early animation, which entailed teams of artists – many of whom would later become key figures in American animation – working under the creative helm of one to try and best the competition. Innovations in animation were part and parcel of the early animator’s work ethic, and this is exactly where Max and Dave Fleischer fit in. The two brothers had been working privately on animation processes, and had already patented a few of their pioneering techniques before they presented their work to Bray. They had come up with a way to make animated figures appear more lifelike than any of the other processes used in the Teens, including those of Bray. Max filed an application for a patent on a process called “rotoscoping” on 6 December 1915, and was granted one on the 9th of October 1917. The process also happened to be the birth of a certain clown.

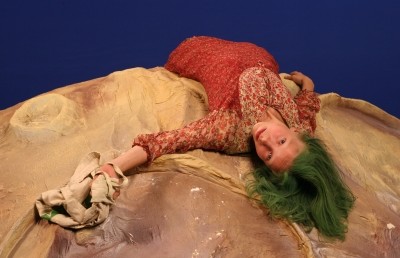

Rotoscoping, as the illustration will show you, is basically tracing. First, live-action film of a subject is recorded, and then it is projected frame per frame onto a glass surface, and the artist traces some, or all, of the character’s movements in order to achieve a lifelike form of animation. This process seems simple enough, but that did not keep it from heavily influencing the aesthetics of different generations of artists. Walt Disney is a dead giveaway, his feature length films are renowned for their fluent, realistic animation, but soon the process was used all over the world – e.g. China’s first animated feature film: Tie Shan Gong Zhu or Princess Iron Fan (Guchan & Laiming, 1941). Of course, most of the time, the process was only partly used, and it also depended on the genre; Warner Brothers’ style, for instance, was not exactly rotoscope-fit, because their characters’ movements were often very exaggerated. The Fleischer brothers, however, did not go for exaggeration too much. The live-action test footage that they recorded consisted of Dave Fleischer moving around in a black and white clown suit, and the rotoscoped result became history.

The Fleischers showed their footage to J.R. Bray in 1917. At that point, Bray had already successfully managed to secure contracts with Pathé and Paramount, and had set up the production company Bray Pictograph – later the Bray Pictograph Company. A test screening was a hit, and Bray signed the brothers to make animated cartoons, the first of which – entitled Out of the Inkwell (Dave Fleischer) – appeared as a Paramount-Bray Pictograph by June 1918. The Fleischers’ Clown was described by one critic as “a wonderful little figure that moves with the sinuous grace of an Oriental dancer” (Motion Picture News, 22 June 1918 – Barrier 23). When Bray moved his Pictographs from Paramount to Goldwyn in 1919, the Clown cartoons were officially dubbed “Out of the Inkwell,” and became a series. These cartoons were dubbed “Out of the Inkwell,” because at the opening of each cartoon – which were actually a combination of live-action and animation – images would be created, or created themselves, out of Max Fleischer’s real inkwell, most of the time by Max himself, who would star as the Clown’s antagonist. Much like The Simpsons, every Out of the Inkwell cartoon had a different opening. In 1921, the Fleischer brothers parted ways with Bray and set up their own studio called Out of the Inkwell films on the strength of their Out of the Inkwell series. The 1921 short Modeling was the first film to come out of their own studio.

Readers unfamiliar with the context of early animation might suspect that the Out of the Inkwell series was a success because of its unlikely early, and seemingly original, combination of live-action and animation. Well, yes and no. No, because (animation) pioneer J. Stuart Blackton had already directed and starred in a short film that combined the two interactively in 1900, namely The Enchanted Drawing. He followed this up with Humorous Phases of Funny Faces in 1906, and acted as director alongside with the great Winsor McCay in the latter’s first attempt at the cinema in 1911, the short film Winsor McCay, the Famous Cartoonist of the N.Y. Herald and His Moving Comics otherwise known as Little Nemo. Frenchman Émile Cohl had also directed similar films, such as the 1908 Fantasmagorie. The extent of interaction between live-action and animation differed, however, especially when comparing the aforementioned films to the Out of the Inkwell series.

Though due credit must be given to J. Stuart Blackton, for in his The Enchanted Drawing the working artist makes cartoon objects become real and vice versa, it must also be noted that the degree of interaction in the other examples was limited to the artist, or solely the artist’s hand, drawing lifeless cartoons on a paper sheet or blackboard. Once the artist stepped out of the frame, the animation could begin. Sometimes, the artist stepped in midway, but that meant the animation had to be temporarily halted until he left the frame again. This was not the case in the Out of the Inkwell films. The Fleischer brothers placed cel drawing sheets over rear-projected live-action film in order to create the illusion that the animated characters were interacting with the real world. This did not mean, however, that they did away entirely with the image of the artist drawing his characters on a board before they came to life, rather they expanded upon it. In the scenes where the characters were on a drawing board without background, animation was achieved on paper instead of on cels.

Modeling starts off with an insert close up of a hand opening the customary inkwell, in which a pen is then dipped. We see the artist scribbling something onto a piece of paper, and another cut reveals his drawing to be of circles, which he – by tilting his page upwards – magically allows to flow off the page and back into his pen. He takes his pen to an actual drawing board and creates a loop that is still attached to his pen. Through animation, the loop tries to escape, and does. After scouring the page, it returns to the pen, only to squirt back out along with the other circles to form a clown. A final touch of the pen creates a flurry of black circles, which detach themselves from the pen to form the coloring of the clown’s outfit. The clown’s hat swirls around because of the experience, he waves at the audience, and then, he brings some attitude to the table: “Why don’tcha use fresh ink when you draw me? I’ve got no more pep than a snail under ether,” a title card reveals.

This short opening sequence reveals the self-reflexive nature of the Out of the Inkwell series that was to distinguish it from most other studios (Barrier 25). The Fleischer Clown is aware of its origins – the inkwell, its creator – Max Fleischer, and its composition – ink. This meta-animation approach opened up many possibilities cartoon-wise, especially given the fact that the Fleischer brothers had the technology to make interaction work to a larger degree than had ever been the case. According to animation historian Michael Barrier, part of that technology – i.e. rotoscoping – is visible in the motions of the Clown at the beginning of Modeling (Barrier 23), and upon close examination one is indeed baffled by the striking smoothness of some of the Clown’s movements when he is urged by the animator to “show some life,” and is accordingly flicked by Max’s finger. The Clown’s self-awareness predates some of the medium-aware characters that would make animators like Tex Avery famous by about 20 years, and the Fleischer brothers exploited this characteristic in a similar vein.

The most obvious self-reflexive factors in the Out of the Inkwell cartoons were … Max and Dave, who were in them. Max almost always played the part of live-action artist, i.e. himself, and Dave was present in the movements and character of the Clown. The two creators thus played against one another: one as creator, one as creation. In Modeling, Max is toying around with the Clown, whilst we see a client enter the same studio, which apparently also holds a sculptor – possibly Dave Fleischer. The client – a caricature in his own right – is there to sit for his bust, but when he catches a glimpse of it, he is not satisfied: “Why—it looks exactly like me!” Max is called to assist, but not before he puts “some energy into this clown,” which he does by drawing him some ice skates and a nice frozen pond, with a hole in the ice. We see how the Clown tries to master the skates, making pratfalls and slipping in the process, and in this hilarity we see how the animation makes perfect use of the optical laws of the camera, something which is more often than not taken for granted in animation.

Throughout the history of animation, we can see how animators adopted techniques that make no sense in an animated world, but that did contribute to the realism and cinematic effect of the animated feature –effects such as lens distortion, rack focus, shallow focus, etc.. The same goes for editing. For a very long time, the editing in animated features was different, i.e. more limited, than editing in live-action motion pictures, and it still is to a certain extent, though the possibilities are basically limitless in animation. When the Clown masters the skates, we see him skate towards the horizon and become smaller, and skate closer and become larger. This use of perspective catches the eye –especially in early animation, which was generally flat– but as if that was not enough, the Clown comes skating really close towards the camera, and sticks his tongue out at the audience as he comes flying by. Editing-wise, however, the animated action generally plays out in long shot and long take, save for the fact of course that the shot scale becomes varied because of the Clown’s movements toward and away from the camera, animated “mise en scène” if you will. It may seem like simple tomfoolery when you see the Clown in action, but there is some serious medium-examination at work here.

The animated adventures of the Clown on the drawing board, which come to include a polar bear and cows, are all the while cross-cut with images of Max and his sidekick trying to figure out what to improve upon the sculpted bust. About halfway through the film, the Clown, probably bored with his animated cow companions, catches on to the live-action and starts sculpting a bust of his own out of a snowball. He draws the attention of the sculpting crew and mocks them as they try to think of a few tricks to make the client’s nose look smaller. Max Fleischer, strict as always, replies by throwing a piece of sculptor’s putty in the direction of the Clown, and through a perfect match-on-action the putty hits the Clown, passing over into the cartoon world without a glitch. The Clown is immobilized by the putty on his head, the weight of which has him turned upside down –cartoon logic at its best– and everyone now gathers around him. Not very clever, for when the Clown frees himself of the putty, he throws it right back, and hits the client in the eye. After that, he dives into the hole in the ice, making himself disappear.

Only, he is not quite gone. He pops up in the real world and skates through the interior of the studio. Matches-on-action get him from one place in the studio to the next, and clever drawing allows him to access different planes of action (background, middle ground, and foreground). He ends up on the real life bust, and hides himself inside when the sculptor and his client return. This plot twist allowed the Fleischer brothers to display some wonderful stop-motion animation, though I guess the term “claymation” would be more appropriate here. We see how the nose is turned into all kinds of weird shapes by the Clown inside. The client notices this and is so startled by the living bust that he falls off of his stool. The Clown decides to scram, but his physical appearance is now a piece of clay that moves about like a caterpillar, albeit a very fast one. Everyone watches in amazement, but when they try to catch him, they end up with nothing but clay in their hands. The Clown is thereby released again, and as he skates back into the drawing, the client leaves in dismay, hurtling a piece of clay at Max Fleischer on his way out. When Max and his assistant go after the Clown, he jumps out of the drawing board and into the inkwell, sealing it shut. Max opens it and pours out the ink, but the Clown does not reappear.

At least not until the next episode, when he returns for more meta-animated monkey business.

Endnotes

1 Ko-Ko was originally known as “the Clown” or “the Fleischer Clown,” and was dubbed “Koko” by the Fleischer brothers in 1923. His name was then hyphenated to “Ko-Ko” for copyright reasons in 1927, when Paramount took over the Out of the Inkwell series and renamed it “The Inkwell Imps” (Maltin 82; Crafton 177), though the earliest use of the hyphenated form seems to date back to 1926 with Ko-Ko’s Queen.

2 One of J.R. Bray’s first stints as a cartoonist was a comic strip entitled “Little Johnny and the Teddy Bears,” which ran in the weekly magazine Judge from 1907 to 1909, and which was obviously inspired by the Theodore Roosevelt inspired Teddy Bear craze. Cf.

Bibliography

Abel, Richard. The Ciné Goes to Town: French Cinema 1896-1914. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Barrier, Michael. Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in its Golden Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Crafton, Donald. Before Mickey: The Animated Film 1898-1928. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1982.

Maltin, Leonard. Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons. New York: Plume, 1980.