Atom Egoyan’s Chloe: Filtering Bergman’s Persona

Every so often film viewing experience grants you a nice moment of coincidental synchronicity that recalls the adage “six degrees of separation”: that the world of film, like our own real one, is not as large as it appears. Even with hundreds of thousands of films in the collective archive of film history, serendipity can raise its head. The coincidence I speak of relates a viewing of two films across two days, completely by chance; on day one I caught up with a film by a director I much admire, Atom Egoyan, Chloe. The day after, as preparation for a class I was teaching, I saw one of the most canonized films in film history, Ingmar Bergman’s Persona. While watching Persona I did not give much thought to Chloe, until I heard a line of dialogue spoken by Bibi Andersson’s Alma character, that echoed in my ears. Where had I heard that line before? Could it have been from a screening of Persona many years ago? If so, why is it only that line that sticks out? Then it dawned on me: I had heard a similar if not identical line spoken by the David character (Liam Neeson) in Chloe. It was too perfect of a coincidence, so my senses became more alert to other similarities. There was one other striking similarity –a frank, explicit exchange by one character to another of a sexual encounter – which made me look more and the deeper I looked, the more similarities I unearthed.

On the surface Persona (1966) and Chloe (2009) seem to have little common, other than being two films featuring complicated relationships between two female characters. Whereas Chloe is plot-driven in a classical narrative sense, Persona is Bergman’s most abstract film, with a plot that can be summarized thusly: a young nurse named Alma (Bibi Andersson) is asked by her head nurse to care for an actress named Elizabet (Liv Ullmann) who has had a psychological crisis and has stopped talking. Not much more develops in terms of plot. The two women take refuge at a beach-side cottage for some rest and relaxation. Alma begins to open up to Elizabet and uses her as a sounding board for her insecurities, fears, and regrets. The sojourn becomes a form of painful self-therapy, with deep psycho-sexual scars rising to the surface and causing aggressive and violent behavior between the two women. Moments of clear objective narration give way to barely decipherable excursions of subjective fantasy and role playing, making it harder and harder to discern reality from fantasy, to discern whether Alma is assuming the persona of Elizabet, or indeed whether they are one and the same person (foreshadowing The Fight Club). The narrative is also routinely disrupted by reflexive moments of near Brechtian disassociation, including an abstract pre-credit montage sequence which makes allusions to Bergman’s prior works, as well as indirect foreshadowing of thematic and formal elements.

In Chloe the film is more clearly a cause and effect plot that is driven by one of the major character’s quest to discover whether her husband is having an affair. A successful married couple live a life of comfort and affluence: Catherine (Julianne Moore), an upscale Toronto gynecologist and David (Liam Neeson), a university drama professor. Their modern home would not look out of place on the cover of Architecture Digest. But something is amiss below this perfect surface. The passion has gone out of their marriage; their young son seems estranged from his mother; and Catherine is suspicious of her husband’s flirtatious nature with every young, attractive woman he meets and suspects he is having an affair with a student. She hires an attractive young call girl named Chloe (Amanda Seyfried) to make herself available to her husband to see if he will bite. Chloe and David first meet at a café. They have subsequent meetings where they engage in sex. As per her client’s request, Chloe relates these meetings back to Catherine in great detail. On some occasions while Chloe narrates to Catherine we see the events she is describing. We assume they are truthful, or at least Catherine has no reason to think otherwise. But as viewers we wonder whether Chloe is a reliable narrator, or whether she has something else to gain by fabricating these sexual tales. Is she resentful of Catherine’s status? Is she trying to live Catherine’s affluent life vicariously? Is she in love with Catherine? Or is she psychological unstable? On Catherine’s side, she begins to show an unhealthy interest in the recounting of these escapades. She is sexually excited by hearing about her husband’s promiscuity; and she begins to show a real physical attraction to the younger Chloe, which is consummated in a sexual liaison of their own. The victim becomes the victimizer. How should we read Catherine’s behavior? Is she a masochist? Is this scenario a convenient outlet for Catherine’s repressed lesbianism? Or is it truly a way for her to get closer to her husband? Is she the mentally unbalanced one?

As you can tell by the above description, Chloe is a more straight-forward character-based narrative than Persona. There are fantasies in Chloe too, but they reside within the elliptical bits of the movie left out –the meetings between Chloe and David that are unseen, or seen but from her possibly skewed subjectivity– which are slowly drawn into the narrative when plot details are revealed. They are not the same kind of cinematic fantasies as those in Persona, which are never tagged as being real or not. Chloe has a direct beginning, middle and end, with a pat resolution (Chloe dies, possibly by suicide, [1] and David and Catherine seem to have saved their marriage). At the end of Persona the two women seem to have come to an impasse and part their separate ways, although nothing is resolved (Was there transference between them? Does Elizabet really return to acting? Will Alma marry her fiancée?).

Persona-like Mirror images in Chloe

Alma

Chloe in film’s opening scene

Catherine

In some respects, Chloe is like Alma in Persona in that she is the one whose psyche is most externalized by Egoyan, beginning from the opening scene where we see Chloe getting dressed before a mirror –which produces the first of many Persona-like mirror images– while hearing her subjective voice-over narration as she describes the physical and psychological attributes needed for her job. The first time Catherine meets Chloe to ‘hire’ her it is at a bar at night. Catherine describes David to her (“tall, good looking”) and instructs Chloe that he has his lunch at the Café Diplomatico. During this exchange between Catherine and Chloe the scene cuts to the actual meeting between Chloe and David, which makes it structurally a flash-forward, but in hindsight may be Chloe’s imagining of the event, rather than an omniscient narration. In the next scene Chloe meets with Catherine and describes her meeting with David as we saw it happen, but then continues to describe what happened after their initial scene at the café cuts away, leaving these events, in a sense, possibly “fictitious” or at least open-ended. Like the Alma/Elizabet relationship, Catherine begins to ask personal questions of Chloe (“How do you do this?”) complicating their professional relations and causing Chloe to open up to her. Catherine pays her then tells her that she wants her to meet her husband one more time, and then she’ll stop the engagement. In hindsight, this cues Chloe to make sure that something of a sexual nature does occur on this potentially last meeting, so that Catherine will be persuaded to continue (which is exactly how the plot plays out). Chloe’s description of their subsequent meeting (at Toronto’s Allan Gardens Conservatory) where they kiss, is intercut with an objectively shot account of it, cementing it as a real event in our minds. As they leave the café and part their separate ways, Chloe, knowing that she is in Catherine’s eyesight, slips (on purpose?) on the wet, slippery sidewalk. Catherine witnesses the fall, goes to her help and they are back together again at the café/bar. This leads to one of the key scenes in terms of the allusions to Persona: Chloe’s explicit recounting to Catherine of her first sexual encounter with David (36’00”), which is a direct echo of the scene in Persona where Alma recounts the salacious details of a casual ménage a four on the beach (the scene also occurs in the same relative point in the narrative, at 26’30”).

Catherine & Chloe (below: Elizabet & Alma)

(Very) Frank Sex Talk

The camera dollies in slowly to them seated on a bench table in the bar. Like Alma’s, Chloe’s detailed description wouldn’t be out of place in a soft-core porn movie. The scene is again intercut with visualizations of Chloe and David. Rather than emit anger or regret, Catherine asks Chloe to provide evidence she is clear of any sexual diseases (perhaps a normal reaction considering Catherine’s profession). It is rare for a female character to speak so frankly and explicitly about sex in a mainstream film. The only other instance of this I can easily recall is in Persona; of course that was an art film, but it was also forty-three years earlier!

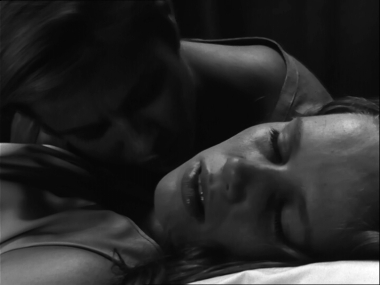

In the next scene the images of Chloe and David together (which I’ll call the “real/fantasy scenes”) begin to assume an identity autonomous from Chloe’s narrating voice, as an amorous scene of David and Chloe at the Allan Gardens Conservatory is sandwiched between Catherine driving in her car at night and Catherine taking a hot, steamy shower. If not real, then who is imagining this now? This echoes Persona, where the two woman seem to (quite literally) fuse; here, it seems as if Catherine’s fantasy is fusing into Chloe’s, or they are sharing in the same fantasy object, David. As if to literalize this, the film performs an exquisite slow dissolve between the two scenes, superimposing David and Chloe in the throes of passion and Catherine masturbating in the shower (the steam on the window in the Allan Gardens matching the steam on the shower stall glass; and Catherine’s Marion Crane-like hand pressed up against the shower stall glass is echoed by David’s hand pressed up against the window). A dissolve back to Catherine superimposes their hands as if to symbolize an attempt for them to touch, to communicate (39’47”). As Catherine exits the shower and enters her bedroom we are almost surprised by the presence of David in bed, somehow assuming in our minds that he is somewhere still at the Allan Gardens Conservatory. It is a beautiful moment that demonstrates the force of editing.

Fusion of Character Identity in Persona

Fusion of Reality and Fantasy in Chloe

The Search for communication

The next meeting between Catherine and Chloe takes place in the same ritzy hotel room where Chloe had earlier met with David for their most recent liaison (47’00”). The setting is daytime and the lighting high-key. In this scene Chloe’s description of their sex (how she “…put him in my mouth, and then he got hard”) again recalls Alma’s similar explicitly detailed description of her casual sexual encounter on the beach in Persona. Chloe’s detailed description of her sexual encounter with David arouses Catherine (as Chloe later says to her, “This turns you on.”). This scene acts as a foreplay to their next meeting (58’00”), where they cut to the chase and have sex. This hotel room’s warmer tones and atmospheric lighting adds a sensuality lacking in the earlier locations where they met. Catherine claims that she sleeps with Chloe as a way for her to be closer to David, to ‘feel’ what he may have felt (or at least this is how she describes it to David).

When we learn that Chloe’s sexual encounters with David were imagined, the film dovetails into two interconnecting fantasies: Chloe imagining sleeping with David, to either inflict pain on Catherine or to get closer to her, and Catherine sleeping with Chloe as a sexual surrogate fantasy. This sexual fantasy of Catherine sleeping with her husband’s lover is a variation of Alma’s fantasy in Persona, where she imagines sleeping with Elizabet’s husband, who plays the fantasy role by acting toward Alma as if she were Elizabet.

Alma becomes Elizabet

What makes this fantasy more cinematically complex, or surreal, is the fact that Elizabet is present throughout the exchange, simply because part of Alma’s fantasy is being accepted by Elizabet as a person of equal value. She clearly has an inferiority complex in face of Elizabet’s star status as an actress, which is another echo in Chloe, who yearns for Catherine’s financially elevated/class status. Egoyan introduces Catherine’s class superiority in her introductory scene, where we see her sighting Chloe for the first time looking down at her at street level her from her physically elevated position. Egoyan cements this class desire in the scene where Chloe seduces Catherine’s son Michael and during the sex scene is less interested in Michael than Catherine’s wardrobe (we see point of view shots of Chloe looking at Catherine’s expensive clothes and shoes).

High angle as class signifier

After what would become their final meeting Chloe tells Catherine that David had admitted to her that this was the first time he had ever cheated on his wife. In hindsight this makes Chloe out to be a sadist, taking pleasure in evicting pain on Catherine. Catherine evicts her own pain back at Chloe when she rebukes her in her office, telling her that the sex they had was “nice” but that their relationship has all along been strictly professional, and offers her a financial settlement to get rid of her (Chloe has not once refused payment, which corroborates Catherine’s evaluation of their relationship as ‘professional’). In a striking shot, Chloe leaves Catherine’s office and walks through the waiting room straight up to a big close-up, stops in her tracks, and stares directly into the camera, bursting with barely contained anger and pain (the gesture of a character looking straight into the lens echoing once again Persona).

Chloe

Elizabet

Once rebuked, Chloe tries to get back at Catherine by stalking her teenage son Michael. From this point on, the film unfortunately veers into Fatal Attraction territory, something not exactly Egoyan’s forte.

When Catherine sets up a surprise meeting between Chloe, David and herself at the Café Diplomatico and David reacts as if he has never seen Chloe (in a most believable manner), the audience (and Catherine) realizes Chloe’s ruse (75’00”). In this exchange, where Catherine admits her infidelity to David, we get the ‘echoed’ Persona-like line, from David, “Jesus Catherine, how many times have I been tempted, and I never did anything about it, never once.” The template for this line comes fairly early on in Persona, approximately 26”, when Alma and Elizabet are having a glass of wine after dinner and Alma begins to confide in Elizabet about her relationship with her fiancée, “I’m faithful to him. In my profession there are opportunities, I can tell you.” There is something implied in this line about the importance of trust that is a crucial notion in both films, and also the moral quagmire of thought versus action: is fantasizing about infidelity or admitting to having entertained the notion, a form of infidelity in itself, or a breach of faith? (This idea comprises the narrative thrust of Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut.)

My initial feelings after watching Chloe were decidedly mixed. I enjoyed the film’s Antonionian use of Toronto’s urban spaces and architecture; I enjoyed the underlying marital tension that infuses every little detail in the film’s opening scenes, the ambient music and soundscape, the overall visual style, and the performances, especially Amanda Seyfried as the emotionally disturbed Chloe. But I felt uncomfortable over the film’s sexual politics, the sense of how Catherine’s angst over her marriage and her life was completely linked to her perceptions of her physical self, and her fear that she was no longer young and attractive enough to “seduce” (her own words) her husband. Somehow her husband’s infidelity (whether it is real or imagined is not important) gets blamed back on the woman (i.e. if I was young and sexy enough you wouldn’t need to go sleeping with your students). Catherine’s dialogue in the scene in which she admits to her husband that she (wrongly) suspected him of being unfaithful, and tries to explain the reason for her lapse of infidelity would make any feminist queasy: “You become more beautiful every year. Every grey hair, every line, everything that happens to you makes you so much more desirable and I feel that if you were to blow on me I’d vanish, I’d disappear. I felt so invisible, so old. I look in the mirror and I don’t know who I am…a person who doesn’t know how to seduce you.” And Catherine’s claim that she slept with Chloe as a way for her to be closer to David, to ‘feel’ what he may have felt would make any lesbian throw their popcorn at the screen!

Historically, Bergman has had a troubled critical reception history with feminist film critics and scholars. Some have championed his works because they give important and juicy roles to female characters; while others have pointed out that these same roles are often filtered through Bergman’s own neurosis’ and/or function as surrogates for his own issues. Persona was no different in this regard, hence as a template for female empowerment it would be problematic. Egoyan has said in interviews that Chloe is about two women’s competing fantasies; this is yet another parallel to Persona, which is also about two women’s competing fantasies. In Persona Alma’s fantasies are externalized by Bergman through the moments of formal ambiguity and complexity, whereas Elizabet’s fantasies are either reflected through content (like the television Vietnam footage and the holocaust photo that visibly disturbs her), or not easily inscribed at all, partly because of her silence and the way the narrative seems to prioritize Alma’s psyche. In either case, what is certain is that neither of these female fantasies are what you would call “positive”! My trepidations toward the film’s possible misogyny were slightly alleviated when I discovered that the screenwriter was a woman, Erin Cressida Wilson (though of course gender is not an immunity to negative representation); the similarities to Bergman’s Persona also, to an extent, deflected some of my fears (by putting it into a film historical context).

I’ll add a final interesting parallel between Chloe and Persona: the way Egoyan draws from the same vampire imagery that Bergman uses (to a greater extent) in Persona, to suggest the way the two characters draw from each other’s life sources. The way in which both sets of characters thrive off each other emotionally and psychologically is reflected, to varying degrees, in the way both directors employ this vampire imagery to metaphorically suggest the characters literally “sucking” off each other. It is no coincidence that the original title for Persona was Cannibalism. The use of vampire imagery occurs more often and more directly in Bergman (who has always had a penchant for drawing on horror imagery). We see it in Elizabet’s dream-like nocturnal visit to Alma’s bedroom, Alma’s return nocturnal visit to Elizabet’s bedroom, and the scene of Elizabet drawing blood from Alma’s forearm.

Vampire imagery in Persona

In Chloe we see it in a series of sensual neck caresses between Chloe and Catherine.

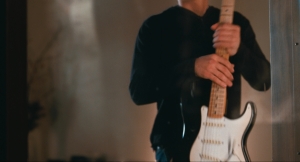

And in the scene toward the end where Chloe stalks Michael from outside his house, seeing him through the glass walled room. As per vampire lore a vampire can only enter into a victim’s home if they are invited in the first time. The editing of this scene suggests this is exactly what Michael does. A long shot of Chloe outside the house with Michael playing guitar in his room establishes the spatial setting. The shot cuts to a closer shot of Chloe as she makes eye contact with Michael and smiles seductively. The next edit cuts to a closer shot of Michael acknowledging her presence and smiling back. As he begins to rise from his chair, the scene jump cuts to Chloe already in the house with Michael trailing behind her.

Here is a brief summary of some of the similarities between Persona and Chloe:

1) Both films square off two woman with competing female fantasies, but from a decidedly male point of view

2) In both cases the shared fantasies involve sexual exchanges with the opposing female character’s partner

3) Across both films there occurs a psychological transference of identity between the two characters

4) A line of dialogue spoken by Alma in Persona, about the many opportunities for infidelity afforded to her as a nurse which she resisted, is repeated in spirit if not verbatim by David in Chloe.

5) Echoing scenes where a woman (Alma/Chloe) divulges the intimate details of a sexual encounter to the other woman (Elizabet/Catherine)

6) Repeated scenes of the two woman talking to each other intimately

7) In both cases, one of the women is younger and more inexperienced than the other in terms of life history (Alma and Chloe)

8) The sets of characters have occupations in similar fields: both Catherine and Alma are in the health service, a gynecologist and a nurse; while Elizabet and David are in the arts, an actress, and a drama teacher

9) Similarity in mise en scène in the proliferation of mirror/window/reflective surface shots, and close-up two shots of the two female characters

10) The metaphorical use of vampire imagery in both films to reflect how the two sets of characters figuratively “draw blood” from each other

11) Direct camera addresses

12) The use of all-white sets

Catherine’s Office in Chloe

Elizabet’s room in Persona

In conclusion, I cannot make any claims for intentionality on the part of Atom Egoyan and the direct reference to Persona I invoke (I will one day revisit the film on BD to listen to Egoyan’s commentary track to see if he makes any references to Persona). They do, however, seem evident through a textual analysis of the films, which at this point is enough. There is also a third possibility: that the connection to Persona is either second-hand, from the original French film which Chloe is largely a remake of, Nathalie –which I have not seen– or that the allusions to Persona are wholly unconscious on Egoyan’s part. I mention the latter because I would be at least very confident that someone with the background and cinematic interests of Egoyan would have at least seen Persona.

Endnotes

1 Chloe’s (implied) suicide by falling backwards from an open window recalls, in its use of super slow motion, the opening death of Lars von Triers’ Antichrist.