Cannes 2011: In a Reflexive Mood

Reflexivity is still in use and working well

In this year’s 2011 Cannes Film Festival there were four films that used the first person point of view, in an autobiographical context. At the center of each movie was a filmmaker, in large part doing most of the filming, and in the process asking questions about the relative power of cinema. These four movies, which all used documentary techniques, were: Pater by Alain Cavalier; Arirang by Kim Ki-Duk, This Is Not A Movie by Jafar Panahi; and Walk Away Renée by Jonathan Caouette. They all seem to express the same dream of making movies in a free context, with a free spirit, and with renewed cinematographic form. The movies also establish a playful, game-like relationship with the spectator.

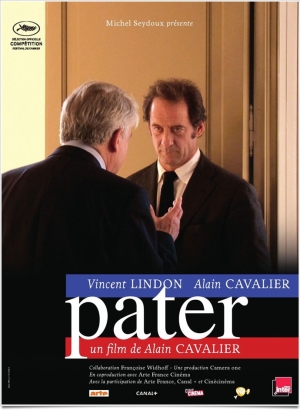

Pater

The title Pater refers to the fact that director Alain Cavalier defines himself as a father figure for the comedian Vincent Lindon (Cavalier’s Catholic upbringing probably explains the use of Latin, Pater for father). As Cavalier films Lindon he asks him to create the figure of a politician that could change the way politics is conducted in France (Cavalier is not afraid to aim very high…and so, he even pretends to be the President of the Republic). Again, as in many Cavalier movies, the film takes the form of a false documentary. In 1990, after establishing a good track record with fiction films (like the great Thérèse), Cavalier decided to switch to filming with his own DV camera, which enabled him to shoot and direct at the same time. The shift led to some of his best films: La rencontre (1996); Vies (2000); Le filmeur (2004), and, his masterpiece, Irène (2009).

Continuing the trend set by Le filmeur and Irene, Pater is an autobiographical movie in a form of a diary. Cavalier mingled with politics in his first (fiction) film Le combat dans l’île (in that movie a young man wants to change the direction of the politic left in his country). In Pater Cavalier turns directly to politics, but the questions remain: Are we supposed to believe in all this? Is politics only a game? While Cavalier seems to stick to his guns and dreams up a new type of politician, Vincent Lindon is clearly playing a game, exceeding what Cavalier could expect. This playfulness adds some welcome humor to the film, but at the same time derails the political aim. Perhaps Cavalier should have gone back to the lessons of Le Filmeur and Irène and do the movie solo. The film, then, works better if considered as a film about friendship rather than politics, as Irène was a movie about the woman he loved most.

Political satire or a film on friendship, Cavalier’s approach remains an intriguing interrogation of cinema. Stylistically Cavalier employs static long takes, punctuated by dissolves after most scenes. The reflexive nature of the film comes to the forefront at the end when Lindon takes over the camera and we get, for the first time in the movie, a shot-counter shot scene. By the film’s end we still wonder what was real and what was not, but perhaps where the film is most truthful is on the nature of friendship.

Arirang

Since 2000 (The Isle) Kim Ki-Duk’s films have been in competition and winning prizes at major film festivals around the world. This year Arirang shared the top prize of the “Un Certain Regard” section (with Andréas Dreisen’s Stopped on Track). Cinéphiles everywhere have seen his movies, but very few Koreans have. Is it because his movies are quite critical of Korean society? Arirang will no doubt have the same effect. It is common knowledge that an actress nearly died during the shooting of a suicide scene in his previous movie Dream (2008). She survived, but the incident left a psychological scar on Ki-Duk, and he had decided to stop making movies. Arirang marks a “come back,” but a very plaintive, desperate, come back; a sort of testament. “Arirang” is an old traditional Korean folk song, which Ki-Duk sings many times in front of the camera, quite loudly. It is a love song full of sadness, in the tradition of the Korean genre of popular music pansori, similar to the American blues idiom. In the song a woman has lost her lover and sings: “Come to me! Come to me! Come and join me!”

Arirang is a one-man show: Kim Ki-duk is the only person we see on camera (he is the main actor), he wrote the screenplay, did the filming, the editing and the sound (including the singing). As such, Arirang is truly an “auteur” movie, a 100% authored cinema. Over the course of the film Ki-Duk ends up having long conversations with himself. Ki-Duk is desperate, he looks like a tramp or a beggar. On one side he is complaining about all the bad things that have happened to him (depression?). While on the other side the simple fact of filming, of making his own new movie, puts him in a state of joy. We know he will come back to cinema; this is what all cinéphiles are hoping for.

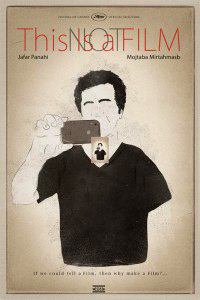

This is Not a Film

Like Ki-Duk (Arirang), but for different reasons, Jafar Panahi is restricted to staying at home alone and using himself as the subject for his movie. Panahi is in “house arrest” serving a December 2010 verdict of a six-year prison sentence and a twenty-year ban on filmmaking, travelling outside Iran and talking with the media. During the filmmaking he is awaiting a court’s verdict on his appeal (we see him on the phone with his lawyer). Like Ki-Duk, he is a filmmaker, and he wants to make movies, even under these poor conditions. Hence the title This Is Not A Movie (clearly an ironic gesture toward the political powers in Iran). And, like all filmmakers, he wants people around the world to see his work. So how does he achieve this? By sending the movie on a USB key, hidden in a cake! Cannes accepted the movie, and did the same for Bé Omid É Didar/Au Revoir by Iranian filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof. By taking these actions these filmmakers are exposing themselves to harder penalties in Iran. But the fight for liberty of expression is always a hot topic in Cannes. For example, while Panahi was arrested for his support of the pro-democracy movement in Iran last year and could not attend, his jury chair was still kept by the Cannes Festival organizers; and in 2009 Cannes showed Bahman Gobadi’s remarkable, clandestinely shot film on the underground music rock scene in Teheran, Les chats Persans.

Like Cavalier’s film, This Is Not A Movie has comic moments, like the presence of his pet iguana, whose free wandering throughout the house acts as a counterpoint to Panahi’s lack of liberty. The movie concentrates on Panahi’s dreams, aspirations as an Iranian and a filmmaker. But his life is mainly a series of frustrations…..

For this movie, and his works in general, Panahi was awarded the “Carrosse d’or” (a reference to the Jean Renoir film Golden Coach), succeeding the likes of Clint Eastwood, Nanni Moretti, Jim Jarmush and Agnès Varda.

Walk Away, Renée

Jonathan Caouette’s Walk Away, Renée is another reflexive movie that dares to communicate to us in an uncanny manner. Caouette introduced us to his family, especially his mother Renée Leblanc (former Acadian), in his debut autobiographical film Tarnation (2004). The two movies share a sort of “Work In Progress” aspect, but are convincing despite, or maybe because of, this aspect. It is again an event-in-front-of-the-camera, as if helmed by a very loose-cannon director. Like Terrence Malick’s Tree Of Life – minus several million dollars– Walk Away, Renée blends dramatic individual lives with cosmic visions. Caouette shows us parallel universes in a decidedly more fun philosophical perspective than Malick’s “new age” philosophy.

The title “Walk Away Renée” refers to a song from the sixties that Caouette’s mother liked very much; “It’s about love lost and someone not being able to reach out to his loved one” (says Caouette). The song echoes the title of Kim Ki-Duk’s Arirang: a plaintive song about love lost. In the Ki-Duk film “Arirang” is the password needed to get through and reach the one she loves. For Ki-Duk we have to understand that the path he is seeking is the one that would bring him back to his first love, cinema. With the events that have followed since Cannes (Panahi’s appeal was refused, and the December 2010 sentence was confirmed) Panahi is on a similar path, searching for his own “arirang” that will see him return to his love, cinema.

Trailer for This is not a Film