Broken Cameras: On the 2012 Boston Palestine Film Festival

The Boston Palestine Film Festival, founded in 2007, takes place in the first two weeks of October in the Boston area, predominantly at the Museum of Fine Arts, but also at other venues including the Harvard Law School. It features a large variety of events, such as film screenings, concerts, and debates. It is part of a broader, international network of Palestinian film festivals (including London and Chicago), spearheaded by Columbia University’s “Dreams of a Nation” festival in New York, founded in 2003.

The Boston Palestine Film Festival represents a specific kind of film festival, a “festival with a geopolitical agenda,” as opposed to “festivals with business agendas” and “festivals with aesthetic agendas,” according to Kenneth Turan’s terminology (65-109). In other words, it is more closely related to smaller, alternative, and politically committed festivals such as the Sarajevo or Havana film festivals than to major venues like Cannes or Sundance, or more specifically art house-oriented festivals like Telluride. Of course, such distinctions, providing us with a useful characterization and mapping of the ever-expanding world of film festivals, should be taken with a grain of salt: even though the Boston Palestine Film Festival’s organizers received the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee – Massachusetts Chapter’s 2008 Dedication to Activism Through Arts award, a clear indication of its “geopolitical agenda,” the festival cannot be described as purely political, but rather as performing, to various degrees, a triple function, cumulating and conjugating business, politics and aesthetics.

More specifically, the festival seems to correspond to Hamid Naficy’s definition of an “accented cinema,” as a showcase of “exilic and diasporic filmmaking” par excellence:

Although it is not strongly motivated by money, accented cinema is, nevertheless, enabled by capital – in a peculiar mixed economy consisting of market forces within media industries; personal, private, and philanthropic funding sources; and ethnic and exilic economies. It is thus not entirely free from capital, nor should it be reduced to it. The accented cinema’s mode of production is divided into the interstitial and the collective modes (…). These modes are undergirded by (…) interdependent, nonprofit, political and ethnoreligious organizations and by a variety of mediating cultural institutions. (43).

The support network of the Boston Palestine Film Festival includes institutions such as the M.F.A., [1] the Center for Arab American Philanthropy, and the A.M. Qattan Foundation, and an enthusiastic team of volunteers and pro-Palestinian activists. This alternative support network appears to be of paramount importance, guaranteeing the very existence of Palestinian cinema in the absence of a properly Palestinian film industry, due to the dire economic and political situation in the Occupied Territories. As Xan Brook has observed:

Feted by the critics and public alike, Palestinian cinema remains a culture in exile, an industry without a home. ‘Let me tell you about the Palestinian film industry,’ says actor-director Mohammed Bakri (…). ‘Very simply, we do not have one. We have some very talented filmmakers, but that’s about it. We have no film schools and we have no studios. We have no infrastructure because we have no country’ (Brook 2006).

Thus, the function of a Palestinian film festival is twofold: facilitating contacts between filmmakers and potential donors and contributors, and constituting an alternative distribution network for works that, with some notable exceptions, (for instance movies by internationally-acclaimed directors such as Elia Suleiman) are rarely made available to the general public. [2] Thus, Palestinian film festivals provide Palestinian cinema with a structure of replacement or ersatz of a national film industry, performing vital functions of funding, production and distribution.

Similarly, the more properly political function of the festival is to constitute an attempt at building a provisional, exilic or “interstitial” public sphere. If, according to Cindy Hing-Yuk Wong, any film festival can be accurately described in terms of Habermasian public spheres, this aspect seems to be of particular urgency in the case of a Palestinian film festival. Indeed, the aim of the Boston Palestine Film Festival is not limited to political activism proper, that is to say showing the support of international audiences and raising awareness about the fate of the Palestinian people. Not only does it allow for the creation of a Palestinian public sphere in an atmosphere relatively free from the numerous obstacles and hindrances that stand in its way in the Occupied Territories, it also enacts and performs Palestinian identity. Illustrating the multiplicity of singular artistic visions and political opinions, the festival emphasizes their convergence and confluence in a single event and a unified public sphere.

Palestinian national identity seems to be in constant need of reaffirmation and self-definition, along the lines of one of the most significant documentaries produced by the P.L.O.’s film unit, Mustafa Abu Ali’s 1974 They Don’t Exist. The title is a bitterly ironic echo of a statement by Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, asserting that Palestinians “do not exist” as a people. Abu Ali, one of the founding fathers of Palestinian cinema, establishes it as a counter-narrative, both an instrument of political activism and a performative proof of existence, disqualifying the Israeli official negation of Palestinian identity while still retaining a sense of doubt, instability, and urgency. Thus, the Boston Palestine Film festival, like its New York or London counterparts “was not simply a celebration of a national culture, but a far more political assertion of a national identity (…) – this was a Festival with much more at stake than most,” in the words of Jared Rapfogel describing the first edition of the “Dreams of a Nation” Palestine Film Festival in New York in 2003. Its sense of urgency stems from the fact that what is at stake is precisely the continuation and perpetuation of Palestinian identity through the spreading and publicizing of discourses – in the case of film festivals of discourses shaped by and spread through a specific medium, film.

They Don’t Exist

Moreover, according to Edward Said, discourses and “storytelling” at large are probably the last line of defense of the Palestinian national struggle, given the fact that attempts at a political resolution of the conflict seem to have come to a dead end: “The interesting thing is that there seems to be nothing in the world which sustains the story; unless you go on telling it, it will just drop and disappear” (Said 118). In turn, this particular significance and sense of urgency seems to put pressure on the festival as a whole, and the very structure and aesthetic agenda of each film in particular. In other words, this productive tension is of paramount importance in shaping the logic of the festival as a whole, as well as the works that it features and promotes. Even if, as we mentioned, accented cinema’s mode of production is not entirely cut off from capitalistic structures, the most interesting and productive dimension for a comprehensive analysis of a Palestinian film festival seems to be precisely this tension between the two complimentary magnetic poles of aesthetics and politics. Thus, to a certain extent, Kenneth Turan’s characterization of the Sarajevo film festival could also be applied to the Boston Palestine Film Festival:

While visits to more conventional festivals like Cannes or Sundance concentrate on rooting out what is new and different, the award-winners and trend-setters, Sarajevo promised a chance to examine the uses and purposes of film at ground zero, to get at the core of how the medium works and what it can mean to people no matter what their circumstances. Like the Hollywood director in Preston Sturges’s classic 1941 Sullivan’s Travels who takes to the road in an attempt to connect what he does with a larger reality, a visitor to Sarajevo could investigate the relevance of film in a setting considerably removed from the fleshpots of the studio system [90].

The essential link between aesthetics and politics, and the performative role of Palestinian cinema as an expression of Palestinian identity can be traced back to its very origins, the activist, revolutionary cinema of Mustafa Abu Ali and the other members of the PLO’s film unit in the early 1970s. Nevertheless, the relations between these two magnetic poles are far from being determined by a fixed, immovable equation. On the contrary, the articulation of aesthetics and politics seems to be in constant evolution, renegotiated according to the situation in the Middle East at large and the Occupied Territories in particular, as well as innovations and trends in the sphere of artistic practices, for both documentary and fiction films. [3]

Thus, the 2012 Boston Palestine Film Festival corresponds to a specific stage in the evolution of Palestinian cinema. According to the chronology laid out by Gertz and Khleifi, after the “Cinema of the Palestinian Revolution” (1967-1982) consisting mostly of political documentaries produced by the P.L.O.’s film unit, the era of “Post-Revolution auteur cinema” (1982-present) is characterized by more personal, auteur productions less heavily relying on a fixed political agenda, illustrating the diversity, contradictions and tensions within Palestinian society itself. [4] The most characteristic format of this period is the fiction feature film, championed by directors such as Michel Khleifi or Elia Suleiman. Nevertheless, even if previous editions of the Boston Palestine Film Festival have featured movies by Suleiman and Khleifi, the 2012 edition was characterized by works in a different format, corresponding to a shift in Palestinian film production that could be described tentatively, in my opinion, as a new stage in the evolution of Palestinian cinema, “Palestinian independent documentary.” Apart from the opening movie, Susan Youssef’s Habibi, a fiction feature set in Gaza that tells the story of two star-crossed lovers, Layla and Qays, the vast majority of the works featured in the 2012 Boston Palestine Film Festival are low-budget documentaries.

Eschewing a fixed, one-sided political agenda (in a marked contrast with the inherently propagandistic nature of the P.L.O. film unit-era documentary production), these films seem to rely both on a global trend, the flourishing of low-budget documentary film production enabled by the use of digital media, dramatically cutting production costs and thereby democratizing access to documentary filmmaking, and on more specifically Palestinian artistic developments. [5] The strong autobiographical component and direct implication of the filmmaker in the movie, use of humor (more often than not humour noir), and sustained attention to the multiplicity and diversity of Palestinian society (as opposed to the relatively univocal tendency of P.L.O. documentaries, emphasizing the need for national unity at the expense of local and individual idiosyncrasies) all seem closely related to the formal innovation of Palestinian fiction feature auteurs such as Khleifi or Suleiman. The importance of alternative voices and points of views in the 2012 Boston Palestine Film Festival, with thematic programs corresponding to concepts ranging from women and gender studies (“Shorts Program: Stories about Women”) to eco-criticism (“Thematic Programs: The Environment”) alongside with more traditional concerns such as the fate of Palestinian political prisoners (“Thematic Program: Political Prisoners”) or the concrete, visceral importance of the land (“The People and the Olive”), is not only due to the fact that most of the organizers of the festival are university professors or graduate students from the Boston area, familiar with the latest developments in American intellectual and academic circles; on the contrary, it seems to reflect a fundamental trend in the Palestinian documentary film production itself. Thus, the festival offered a vast, multifaceted panorama of Palestinian experiences and visions: an intimate conversation with the filmmaker’s grandmother and her struggle to keep her house (Georgina Asfour’s The Fig and the Olive), a chronicle of water shortages in the Aida refugee camp in Bethlehem (Mohammad Al-Azzaz’s Everyday Nakba), or the daily life of Arab Israeli Bedouins in the Negev desert (Jillian Kestler D’Amours Sumoud). The plurality and diversity of Palestinian experiences was further emphasized by a number of productions illustrating contacts and cultural exchanges between Palestine and the rest of the world, documenting foreigners traveling to the Occupied Territories (Aaron Dennis’ The People and the Olive, about American marathoners running through the West Bank to replant olive trees uprooted by Israeli settler), the Palestinian Diaspora (Ana Maria Hurtado’s Palestine in the South, about a Palestinian family settling down in Chile), or comparing the fate of the Palestinian people to the one of other oppressed peoples around the world: Konrad Adener’s Enemy Alien draws a parallel between the imprisonment of a Palestinian human rights activist by the I.N.S. to Japanese American internment camps during World War II, whereas the controversial Roadmap to Apartheid, one of the festival’s highlights (owing more to its strong political message than to its relatively banal aesthetics of a conventional third-person voiceover documentary), compares discriminations against Palestinians by the Israeli authorities with the South African Apartheid regime.

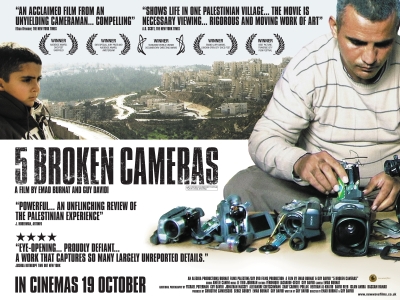

The other highlight of the festival, and in my opinion the most formally innovative and visually arresting movie it featured, is Emat Burnat and Guy Davidi’s Five Broken Cameras. This film relates the daily struggle and uphill battle (both literally and figuratively) of the inhabitant’s of B’lin, a Palestinian village threatened in its very existence by the erection of the Israeli separation barrier and the apparently irresistible expansion of a neighboring settlement at the expense of the Palestinian villager’s lands and olive groves. The chronicle of this daily resistance of the inhabitants of B’lin against their own disappearance, marked by an unending cycle of demonstrations, acts of resistance, and brutal repression by the Israeli army, is narrated in the form of a diary kept by the filmmaker, Emad, an inhabitant of B’lin, professional photojournalist and compulsive user of digital videocameras. The necessity of recording the tragic events unfolding in the village, but also the relative fragility, vulnerability, and subjective nature of this testimony is illustrated in a number of ways. The compulsive act of compiling a personal digital video archive allows for a constant mixing and intertwining of the private, even intimate sphere (conversations between Emad and his wife, family, and friends, village festivals, etc.) with the sphere of political events. According to Hamid Naficy, the insistence on private, daily life as a characteristic of “accented cinema” is in itself highly political:

The performative expression of dailiness by exiled and disenfranchised peoples is a countermeasure to the official pedagogical representation of them, which tends to abstract them by stereotyping, exoticizing, and otherizing. This may account for the emphasis in the films of (…) accented cinema on “document-like” descriptions of mundane routines and detailed activities that slow the film’s pacing. However, these routines and details carry with them highly significant cultural, national, and critical import (117).

Official Five Broken Cameras Trailer

Five Broken Cameras is also more explicitly political: demonstrations against the separation wall at B’lin find echo and elicit support across the West Bank and even internationally. Israeli peace activists and Western supporters feature prominently in the documentary, illustrating the international openness of the new school of Palestinian independent documentary (emphasized by the rather odd fact that Emad’s wife comes from the Palestinian Diaspora in Brazil). The cooperation between Emad Burnat and the Israeli filmmaker Guy Davidi is also highly significant. Co-director of the movie, peace activist Guy Davidi is the author of the voice-over commentary said by Burnat himself. Breaking a form of taboo, several recent Palestinian feature films (including Elia Suleiman’s works) were partly funded by Israeli organizations. Here, Burnat and Davidi seem to be taking this process one step further, as the structure and the very “voice” of the movie are based on a Palestinian-Israeli cooperation. Furthermore, the mixing of public and private also corresponds to two key elements: if Emad is the first-person narrator and “diarist” providing us with a very personal, often witty voice-over commentary, he seems to disappear behind his own camera, as it were. As he is holding the camera most of the time, he only appears in a very limited number of shots. Instead, his youngest son features prominently in the documentary; the film establishes a parallel between his growing up and the evolution of the situation at B’lin, both in terms of a “comic relief” (his bewildered, naïve remarks, often pointing at some of the most absurd aspects of the conflict) and of his gradual understanding of the situation.

But the most important character in the documentary is probably the camera itself: the personal trajectory of Emad and his family is punctuated by the successive acquisition and destruction of five different digital cameras. Often brought as a present by friends, relatives or supporters, the camera is described as both powerful and fragile. Investing Emad with a mission and giving him, on his own account, a feeling of invincibility, the camera constitutes a way to document abuses against Palestinian civilians, a “weapon” that Emad is constantly pointing at the Israeli soldiers and settlers as a symbolic answer opposing the power of images to guns and tear gas. But conversely, the camera is described as a rather frail device: each of Emad’s five cameras is “killed in action,” as it were, destroyed during the repression of demonstrations against the separation wall by the Israeli army in a variety of ways (a bullet straight into its lens, a tear gas grenade, an angry settler smashing it on the ground, etc.). Not only do we see the “last moments” of each camera, the dissolving of the image in a blur of large pixels and finally into a dark screen, but the movie itself, shot with five different cameras of varying qualities, is a succession and “suturing” of heterogeneous images, neatly divided in five chapters, one for each camera. These qualities of formal innovation, deep personal involvement, reflection on the function of the digital medium and on the paradoxical nature of testimony (at once necessary, empowering, and incredibly fragile) contribute to make Five Broken Cameras into a prime example of contemporary “accented cinema” at large, as defined by Naficy and more specifically of what I would argue is the latest stage of development of Palestinian cinema: independent, formally innovative, auteurist low-budget documentaries.

Indeed, the metaphor of the broken cameras seems to encapsulate the very nature of the Palestinian experience: relying on storytelling, surviving through the perpetuation and displaying of narratives it is also based on a “broken gaze,” a form of scopic drive that, though able to elicit support and resonate with foreign audiences, is also always threatened in its very existence, constantly repressed, interrupted, and revived, in an apparently unending cycle that confers to Palestinian cinema a particular sense of tragedy and urgency.

Endnotes

1 In a spirit of conciliation, the MFA also hosts a Jewish Film Festival in November.

2 Another major paradox of Palestinian cinema is that its international distribution network, though mostly limited to a handful of film festivals (New York, Boston, London, Chicago), is still far more comprehensive than the distribution network in the Palestinian Territories themselves, which is literally non-existent. In the words of Xan Brooks, “the irony is clear: visitors to the Palestine film festival in London will have had greater access to Palestinian films than the vast majority of Palestinians.”

3 Often introduced through the mediation of young Palestinian graduates from Film Studies programs and Film Academies in Europe and North America.

4 These movies, commonly referred to as “Cinema of the Palestinian Revolution”, were designed as instruments of a political struggle, and were structured along the lines of the P.L.O.’s official doctrine: notions like clarity of message, political and testimonial value, and immediate propagandistic impact at the expense of individual artistic projects, characterized the agenda of these productions. Nevertheless, their innovative use of montage techniques and uncompromising political nature also kindled the interest of Western European engagé audiences and directors, first of all Jean-Luc Godard, who collaborated with Mustafa Abu Ali and included Palestinian documentary footage in his movie Ici et ailleurs (1976).

5 To a certain extent, one could say that the relatively monolithic nature of the production of the Palestinian Revolution era is due both to a different understanding of the nature and purpose of engagé filmmaking, and the unavoidable concentration of the means of film production in the hands of the P.L.O. film unit, the only available structure for Palestinian film production, development (the P.L.O. film and photography laboratory, first located in Amman, then in Beirut) and distribution.

Works Cited

Abu Ali, Mustafa, They Don’t Exist. 1974.

Brook, Xan. ‘We have no film industry because we have no country’, The Guardian, April 11th, 2006. Online. Internet. November 9th, 2012.

Gertz, Nurith and Khleifi, George. Palestinian Cinema: Landscape, Trauma, and Memory. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Hing-Yuk Wong, Cindy. Film festivals: Culture, People, and Power on the Global Screen. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2011.

Naficy, Hamid. An Accented Cinema: Exilic and Diasporic Filmmaking. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

Rapfogel, Jared. “A Report of Dreams of a Nation – a Palestinian Film Festival”, Senses of Cinema 25 (March 21, 2003). Online. Internet. November 9th, 2012.

Said, Edward. The Politics of Dispossession. London: Vintage, 1995.

Turan, Kenneth. Sundance to Sarajevo: film festivals and the world they made. University of California Press, 2002.