That Obscure Object of Horror

Francis Mankiewicz’s Les Bons Débarras at Thirty

These mountains reign alone,

they do not share

The transitory life of woods and streams;

Wrapt in the deep solemnity of dreams,

They drain the sunshine of the upper air.

Frederick George Scott, The Laurentians

The sound of Canadian filmmaking can be heard in any one of its products, but there are certain titles that distinguish themselves, that inspire viewer faith more readily, speak to their audiences more intimately. These stand in the empty space left by other works that are less articulate, in some sense failing to convey their true subject: the audience itself, forever seeking dialogue with its film fare. They may be dreamt, anticipated, and perhaps lived, but, for one reason or another, have not entered fully into the vast and impatient realm of public entertainment. Such works are naturally exceptions in an industrial art that bestows ubiquity on the most fleeting of viewing trends. This concerns trends in image definition, manipulation, and projection/screening technologies, as much as the immediate tastes of the juvenile male, but even in commercial artworks the test of durability is in the application, not the app. CGI and 3D technologies are here to stay, more or less, and James Cameron’s latest offering is a gorgeous piece of work (a quarter of a billion can do that for a picture), but will the singularity that is Avatar last thirty years? Will it still look fresh in three? Looking back through the filmographies of other, less bankable Canadian directors, there are more than a few features worth revisiting, if only because they were in some way unseen at the time of their initial release. Premiered in 1980 and narrowly screened in North America the following year, Francis Mankiewicz’s Les Bons Débarras is a title that has managed to stand at least a preliminary test of time. That it was recently given an acceptable transfer to DVD might have remedied its underexposure, though that release – from Dep Distribution – has rapidly fallen into obscurity (consumer copies of the film now typically fetch over $50). Of course, even wide video release is no guarantee that the streaming, renting, on-demand public will give any feature the patience it requires, much less deserves. At best, admirers of Les Bons Débarras can merely point out that it rewards both finding and return viewing, as the greater part of its gifts are not given in a direct or explicit fashion. Indeed, key aspects of the film have remained all but invisible to its most discerning viewers, and the result has been a sleeper of a different order: a film that appears to have dreamt, spoken, and sung for itself, where its audience can’t.

At first glance, Les Bons Débarras has a number of things working against its public appeal. There is the bitter, unsentimentalized poverty of its characters, their easy cruelty and disregard of one another, the rugged-yet-mundane setting in Quebec’s Laurentians, a kind of limbo built from wooded, back road locations, but also from an assortment of restaurants, liquor stores, indoor malls, intersections, and highways (on which the principles seem to spend much of their time). Despite featuring a marketably precocious child actress, Mankiewicz had to have been aware of the material’s dim commercial prospects, at least beyond the Quebecois audience, that relatively small but culturally jealous segment of the North American populace that has, in fact, sought to ratify its distinction from the rest of Canada. The event that best illustrates this struggle is the Quebec independence referendum of 1980, the same year of Les Bons Debarras??’ release. One can imagine how the political climate at the time would have amplified the film’s disavowal of nostalgia, notions of rural innocence, and all things sweetly provincial, in effect linking it to a distinct and widely inaccessible zeitgeist. Not surprisingly, Mankiewicz’s ??Les Bons Débarras is in many ways the antithesis of Claude Jutra’s Mon oncle Antoine (1971), in part because there is so little visually to recommend the film. Expertly lensed by Michel Brault, the austere mountain landscape in which the story takes place is expansive but curiously unspectacular, without a tourist in sight (one aspect of the location that is purely a conceit of atmosphere). There is an air of stale romanticism to the proceedings, but a flat greyness is also prominent, in both interior and exterior spaces, contributing to a sense of economic and spiritual destitution. The film’s even lighting strategy imparts a subtle, ethereal glow to many of its scenes, though without sacrificing visual texture. Diffusion greatly enhances the registration of grit, blemishes, and surface detail – so often erased or disguised in other feature films – causing principle characters to merge with, rather than distinguish themselves from, the earthiness of their autumn environment. Mankiewicz said of the cinematography: “We didn’t want high contrasts. Even when the sun was out, we shot with backlight so as not to get sharp shadows across the face. We wanted a very textured picture, in which you could feel the earth, the leaves, the house and the texture of people’s faces.” [1] Within this drab setting, the performances and use of language are so assured, and the source music so sparingly and devastatingly employed, that Les Bons Débarras??’ epic tragedy of small lives assumes an almost cosmic dimension. The prominent role of voice in ??Les Bons Débarras is due largely to the iconoclastic Réjean Ducharme, who brings his skills as a lyricist to bear in creating an anger, freshness, and desperation of speech that never sounds written. Thomas Carlyle addresses this in a way that relates quite directly to Ducharme’s script: “A musical thought is one spoken by a mind that has penetrated into the inmost heart of the thing; detected the inmost mystery of it, namely the melody that lies hidden in it… [S]peech, even the commonest speech, has something of song in it; not a parish in the world but has its parish-accent; the rhythm or tune to which the people there sing what they have to say! Accent is a kind of chanting; all men have accent of their own–though they only notice that of others. Observe too how all passionate language does of itself become musical with a finer music than the mere accent; the speech of man even in zealous anger becomes a chant, a song.” [2] To be sure, the dialogue of Les Bons Débarras is sometimes contrived in a diegetic sense, reflecting the manipulation common to child-parent relationships. What stands out is the film’s favoring of close-ups and dialogue over a musical score, which is notably absent. The use of a live theater model would seem to explain this unusual approach to sound in what is ostensibly a melodrama. When poetic verbal expression is achieved in a theatrical context, as it so often is in Les Bons Débarras, the need for distinctions between speech and music evaporates, as per Carlyle’s comment, with the scoring, if present, tending to either fade into the background mentally, or appear invasive. With the help of sound designers Henri Blondeau and Michel Descombes, Mankiewitcz appears to have hedged his bets by avoiding a score altogether.

The production also managed to resist the temptation to interject foley during quieter moments, striking an extraordinary balance between sound and silence that is all but lost in contemporary features. The frequent silences encourage appreciation for detail until the operatic suicide of one of the protagonists, a sequence that has the power to overwhelm expectations formally if not thematically. It was this sudden shift in pacing and sound use that caused Janet Maslin to misread the film as attempting to escalate “into a thriller, its flair for atmosphere and detail [becoming] overshadowed by the inadequacies of the narrative.” [3] If anyone associated with the production hoped that audiences would find the elements and event of this suicide thrilling, they might have made a film more familiar to American critics, but it wouldn’t have been this one.

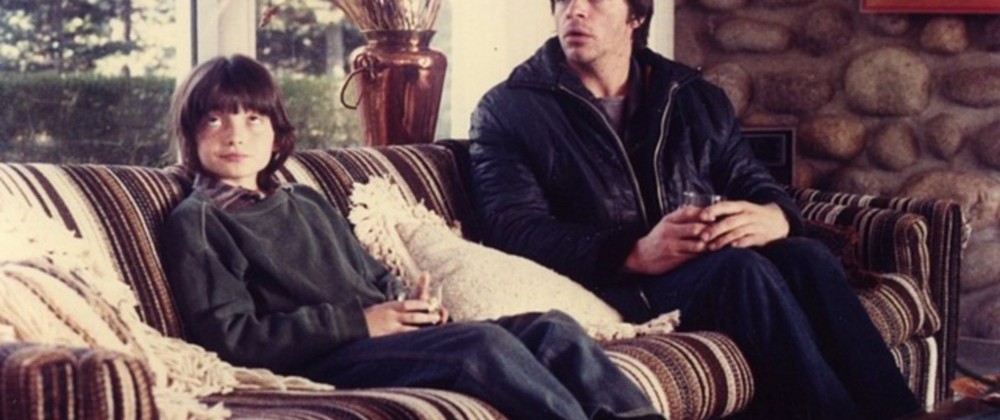

The narrative appears at first to follow Michelle (Marie Tifo), head of a dysfunctional household that subsists by cutting and delivering firewood to a handful of wealthier homes. Michelle’s chief concerns are her mentally disabled brother, Guy (Germain Houde), and her thirteen year old daughter, Manon, (Charlotte Laurier in a hypnotic, now classic performance). Michelle struggles to maintain sobriety, though a past lover, Gaëtan, threatens to derail this effort. In spite of Gaëtan’s semi-playful overtures and improvised poetry, Michelle manages, for the most part, to keep a cool, business-only position; her relationship with a local policeman reflecting her ultimate goal of order and stability. Meningitis has left Michelle’s brother Guy in a state of perpetual childishness, a clearly frustrating condition that is both compounded and relieved by alcoholism. Guy lacks an adult’s capacity for language, speaking perhaps six words in the entire picture. In contrast, his niece, Manon, is strangely lacking in innocence. She is the shrewdest figure in Les Bons Débarras, and when opportunity allows, she expresses her hatred for her uncle with a cruel poetry adjusted to his level of understanding. As the story progresses we realize Manon’s is the dominant voice, and it is her ultimate indifference to Guy’s death from which the film derives its title (“Good Riddance”). Though the script is filled with rhyme and repartee, it is where the characters do not speak that they reveal themselves most completely. These moments are made to bear a greater dramatic weight by their contrast with the command of speech, demonstrated in more dialogue-heavy scenes, the best of which feature Manon.

Quite economically, we are permitted to hear, rather than see, Manon’s half-hearted engagement with work and school, and her all-consuming pursuit of her mother’s love. In this pursuit, Manon views Guy as a competitor, as she does her mother’s police officer boyfriend, Maurice, whom she claims sexually assaulted her in a bid to dissolve their relationship. Stories, reports, gossip, lies, verbal seduction, and wordplay of various sorts are a mainstay of the film’s soundtrack, and these serve a dramatic function typically met by extra-diegetic music. All that this anti-heroic family is made to suffer, by the world and their own will, would seem perfectly evident, without the benefit of hidden dangers to generate suspense or fear regarding the family’s future. There is one moment in the film, however, when the subtext of the narrative is so unsavory to viewers that it is readily passed over by the conscious mind, only to amplify the film’s mysteriously disquieting tone.

I have screened Les Bons Débarras for scores of students, read scholarly assessments of the film, and discussed it with many others, some of them learned cineastes. Still, three decades after ??Les Bons Débarras??’ initial release, I have yet to hear mention of this pivotal event in Manon’s characterization. Superficially, the closest we get to it is a simple image of Maurice’s squad car receding down a highway. At the beginning of this shot we hear Manon’s remark to Maurice in voiceover: “I’m advertising… You interested?” The line is followed by a long pause, filled only by the sound of the car’s tires against the black-top, and cut with a slow fade to black. The implication is clear, yet we resist its concise expression of the extent to which Manon is willing to go to secure her mother’s attention. It speaks to the sophistication of the film that even attentive viewers, in spite of being given evidence of Manon’s gambit, do not consciously acknowledge its fruition. This suggests that the narrative is received extra-consciously, the filtering mechanism for the hidden drama’s most unacceptable information working from some unspoken portion of the conscious mind, or elsewhere (e.g. the simultaneously viewing subconscious). Manon’s own body, very likely her virginity, is secondary to her goal, and therefore expendable. We may conclude that the thing ‘advertised’ is not even sacrificed, or mourned, but forced aside as in war. The depth of the betrayal is more profound than Manon’s spurring of Guy’s suicide, and yet, mercifully, its expression in the film allows the audience a means of escape from its heat. Like so many others, David Denby took the offer, writing of Manon’s strategy against Maurice that she simply “dispatches him easily enough.” [4] The implied seduction is only framed chronologically, not graphically depicted, aside from the symbolic value of Maurice riding a child’s bike. In the following scene we are allowed the image, bolstered by an indignant Maurice, that Manon is simply lying mischievously. Though this conclusion is virtually impossible with close examination of the events as presented, the emotional content of the film, with its affecting portrayal of the principles’ lives and relationships, make its conscious recognition just as difficult. Similarly, the soundtrack and mise-en-scene, presenting conscious experience in an immediate sense, are formally obliged to counter the expression of this horror, though they are designed to present it with the aim of deep recognition. As a form of child sacrifice, the latent image of the event re-emerges for the viewer in the more graphic portrayal of the child-like uncle’s death, and perhaps still later, in the liberated theater of the dream.

The absence of a score benefits the narrative in various ways, primarily by isolating the characters and the distinct sound of their struggles. There are hopes, certainly, and sanctuary (e.g. Manon bathing, reading Wuthering Heights) but these do not leaven the austerity of the family’s circumstances, nor are we, who are privy to the protagonists’ most intimate experience, allowed the distancing effect of an extra-diegetic score. At the odd moment when one does seem to arise, its presence is revealed to be more mundane. For example, the radio broadcast of a frenetic piano composition during an argument between Manon and Guy, or Vivaldi’s Il Pastor Fido, which introduces Madame Viau-Vachon’s home and, we find, happens to be playing on her stereo. One complex exception to this is the use of Puccini’s O mio babbino caro. Though it begins on the radio in the family van that Guy deliberately crashes, the music’s increasing clarity signifies penetration to the interior state of the character. This is hardly an innovation, but it is an extraordinarily nuanced and affecting use of source sound. On one level the passage of music is linked to the unattainable object of Guy’s affection, M. Vachon (Louise Marleau), due to the aria’s association with high culture, and because it is Guy who appends it to her. In his fantasy at this moment, which both he and the audience realize to be fantasy, Vachon takes notice of his idealized self, smiling as she leaves her pool to welcome him. This vision of homecoming is inter-cut with the violence of Guy’s self-immolation, incited by Manon and Vachon’s unwillingness to look at him. In the earlier scene to which Guy’s fantasy refers, we are led to believe, through a series of careful compositions, that M. Vachon may in fact be able to see the barely hidden Guy, as he lurks outside her house at sunset. She looks in his direction, but is apparently incapable of acknowledging his twilight presence between water and land, subconscious and concrete, silent and spoken. There is no gasp or protest from the admired, and the enchanted Guy does not state the business of his visit until nightfall (“the collar…the collar!”), at which point Vachon yells at him fearfully. The class rift featured in the two scenes calls to mind Bertolt Brecht’s comment about the rich: “They make the poor, then don’t want to look at them.” On another level, Guy claims the aria for himself, and its forlorn character is sufficient to make the Italian lyrics his own at this, his sharpest, most despairing moment of introspection:

bq. I want to go to Porta Rossa to buy the ring! Yes, yes, I mean it And if my love were in vain I would go to the old bridge and throw myself in the Arno! I fret and suffer torments! Oh God, I would rather die! Papa, have pity, have pity!

Guy has learned the essential meaning of these lyrics with Manon’s help, and the silencing effect of his suicide is doubly damning for her hiding of the act, his final expression.

Where does the power of Manon’s voice come from? The scene that best addresses this also centers on Madame Vachon. The second visit to her home brings Manon’s fine and coarse elements into direct and constructive opposition with one another, and like the suicide scene contains one of the film’s most elaborate sound strategies. M. Vachon symbolizes to Manon worldliness, detachment, and a quiet ruthlessness; in short, an older version of herself. But, while there is a certain kinship, no warmth exists between the two females. We overhear Manon speaking to herself as she dismisses every aspect of the better life she encounters. Observing Vachon in the dining room (speaking on the phone, dispassionately, to a lover), Manon remarks, “Great love story,” and goes on to quietly and sarcastically point out other elements of the setting: “Great music… Great paintings… Great books.” There is an interesting parallel here between the depiction of upper crust, French Canadian life and the surreal encounter that concludes Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). In that scene the protagonist observes an older version of himself, seated at a dinner table in an adjoining room, his back turned to his past as his past looks on. The eerily alien decorum of the Louis XVI apartment is finally shattered by a breaking wine glass. [5] In Les Bons Débarras, Mozart’s Concerto K.448 is the prime indicator of the brittle and blinkered life of Quebec’s leisure class, and it appears incapable of selling its fantasy to the cynical Manon. But this is before the music is given words to counter the girl’s offhand remarks. The strings of the concerto swell as Manon discovers and lovingly pores over a leather bound copy of Wuthering Heights, which Vachon gives to her. Manon’s fascination with the novel is not purely aesthetic (lending irony to the music), nor is it quite the book’s dialogic relationship to her unhappy life on Lac Barrette. Wuthering Heights is a favorite text, though not the text, of Manon’s hidden self. We hear her reading the book privately throughout the film, aloud and in voiceover. Why does it speak to her so well that she gives it her voice? Aside from the pleasure of escape and/or consonance it provides, Manon feels instinctively that she must master the text to master her coarseness, and thus gain entry to the world of privilege M. Vachon and Emily Brontë speak for. Somewhat perversely, even horrifically, this makes her pursuit and emotional torment of her mother a strategy of subjugation. To conquer her home on Lac Barrette and assume Vachon’s, she must make Michelle her daughter. The transposition of mother and daughter is uniquely destructive, in spite of art being its instrument. Manon does not quite achieve her goal, perhaps, though in the final scene she acts as if she has, shielding her mother from the world of Lac Barrette and beyond, reading her asleep as she would her own child. As the credits roll we are aware of the two sleeping, and that they must wake at some point, but the film grants them a respite; the silent music of the untold dream.

Endnotes

1 Interview by Joan Irving, “Francis Mankiewicz: To Berlin with Love,” Cinema Canada no. 63, March, 1980, p.14

2 The Collected Works of Thomas Carlyle, Chapman & Hall, London, 1864, p.246-247

3 From Maslin’s review, The New York Times, January 15th, 1981

4 “Enfant Terrible,” New York Magazine, Jan.26, 1981, p.47

5 The parallel can be seen later, when Michelle’s extended family is together at a late night skating rink in a rare light moment. The indoor facility plays Strauss’ Blue Danube while the figures wordlessly circle the rink and each other, each high on alcohol (including Manon), suggesting a state of spatial and ontological flight, and freefall. Through source music and figuration the scene evokes the space station sequence of 2001: A Space Odyssey. That idealized vision of human aspiration is the cultural/technological opposite of the scenario at the rink, and for this reason it is all the more strangely affecting. If these parallels with Kubrick’s film are deliberate allusions, as they appear to be, the link may be inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey??’s cynicism regarding language. “Words, the prima material of concepts, are tools. And ??2001: A Space Odyssey is a movie about the invention of tools, the development of techniques that separate man from his savage environment and yet give him an increased vulnerability to that environment. Many critics have noted the utter banality of the dialogue in the film. But that banality, whether through genius or inadvertence, makes it the most eloquent of sound films: it is about sound, about the word in space and in Space. Pennies dropped hopefully into the abyss, each cliché in 2001: A Space Odyssey gives back a tinny echo which is unmistakably inadequate, unmistakably human.” Frank D. McDonnell, The Spoken Seen: Film & the Romantic Imagination, Johns Hopkins Press, Baltimore, 1975, p.65