“African” Cinema: A Comparative Look at Blood Diamond and Ezra

Nigeria vs. Hollywood

When civil war broke out in Sierra Leone in 1991, we did nothing. Sixteen years later, we sit in a movie theatre to watch what we did nothing about. We sit back while our views and morals are shaped by dialogue, camera movement, the performance of a young man or woman, and the perfect execution of an edit or sound cue. A stranger takes it upon him or herself to orchestrate our exposure to Africa, while we idly watch these films believing in their accuracy. However, accuracy is not always the problem; it is the interpretation of the accurate facts that must be considered. The relationship between facts and their portrayal varies greatly according to, not only the writing and directing of a film, but aspects of production value (such as budget, star power and cinematography). The Hollywood film Blood Diamond (Edward Zwick, 2006) and the Nigerian film Ezra (Newton I. Aduaka, 2007) deal with a similar subject matter –the consequences of civil war on the people of Sierra Leone as a result of conflict surrounding the diamond trade. As a high profile Hollywood film Blood Diamond has the advantages of star power and production value over Ezra. However, the human crisis is overshadowed by gratuitous violence, and an emphasis on unrealistic sub-plots and uneven character development. In contrast, Ezra is a simpler, personal take on civil war. It focuses on the psychological effects the war has had on one young man, the titular Ezra (Mamoudu Turay Kamara), and the people helping him to recover. The viewer experiences an intimate story and is given the opportunity to connect emotionally with the main characters. However, Ezra is not a polished Hollywood film, which makes it more difficult to market to a mainstream audience. While Ezra impresses stylistically, it offers nothing new in terms of cinematography. Each film brings different strengths and weaknesses to the telling of a fact-based fictional story about the atrocities committed during Sierra Leone’s civil war. While Blood Diamond has reached a wider audience, I would argue that, ultimately, Ezra contains greater insight into the horrific world of the diamond trade.

Blood Diamond, directed by Edward Zwick and written by Charles Leavitt, was a success at this year’s (2006) Academy Awards. Zwick, who comes from Winnetka, Illinois, has directed several Academy Award winning and acclaimed films (Glory, Legends of the Fall, and The Last Samurai). He is a veteran Hollywood filmmaker whose work includes elements which foster mainstream appeal (violence to heighten dramatic effect, major star power, pre-release marketing hype, etc.). Zwick’s most recent film, Blood Diamond, follows this tradition. It is a big budget action/drama film with an A-list cast. Although shot on location in South Africa, Mozambique, and the United Kingdom it is considered a US production.

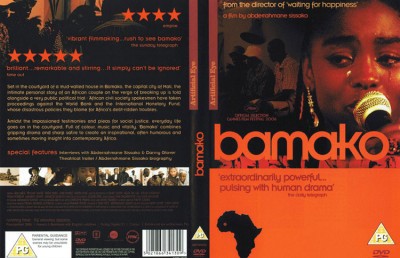

Ezra was directed by Newton I. Aduaka and was co-written by Aduaka and Alain-Michel Blanc. Aduaka was born in Ogidi, Eastern Nigeria, in 1966. In 1970 his family sought refuge in Lagos after the Nigerian Civil War (also known as the Biafran War) of 1967 to 1970. In 1985 he moved to England. After graduating from London International Film School he went on to direct critically acclaimed films in a style that has been referred to as “personal, cutting-edge and uncompromising” (screenonline.org.uk). His first feature, Rage, was the first independent film by a black filmmaker to gain national release in Britain. The film won many awards, garnering acclaim around the world. Since then he has built his career and reputation through international film festivals (screenonline.org.uk). Ezra is a French/Nigerian co-production shot on location in Rwanda and, like Adouaka’s previous work, comes from a highly personal place. It was awarded the Yennenga Stallion, the highest prize at the biennial African Film Festival FESPACO. Even with this cursory look at the respective filmmakers of Blood Diamond and Ezra it is clear the two directors approach their material from different schools of thought: Zwick uses Hollywood conventions to create high tension dramas for mainstream audiences, while Aduaka works through the independent system to create films with a more personal content.

The description of Blood Diamond on the Internet Movie Database reads, “A Hollywood movie tells an African story full of death and violence.” While there is more to the story, this quote accurately describes the film’s heavy overtone. The film is set in 1999 in Sierra Leone during the chaos of a civil war which was fueled by the conflict (or blood) within the diamond trade. Solomon Vandy, played by Djimon Hounsou, is a Mende fisherman on a quest to find his kidnapped son Dia (Kagiso Kuypers) after the rebel army destroy his village. Danny Archer, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, is an illegal diamond smuggler who agrees to help Solomon find his son in exchange for a rare pink diamond Solomon has hidden. In order to find Dia and the diamond they must make their way through cities and jungles while surviving the war between the rebel forces and government army. The film becomes a fantastic display of bloodshed and gore as the two men hunt for their most prized possessions.

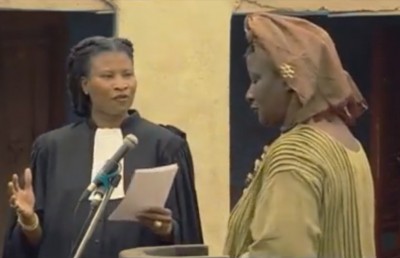

Ezra, also set during the time of civil war in Sierra Leone, is the story of a young boy who at the age of seven is kidnapped and forced to train as a rebel soldier. The film takes place nine years later as Ezra recounts to the Truth and Reconciliation Committee his experiences as a rebel soldier and the reason he chose to desert the rebel army. Ezra must come to terms with the fact that one night he unknowingly raided his own village and was accomplice to the murder of his family. His story is set against the reality of how children are turned into combatants. The role of the diamond trade in fuelling the civil war is involved but is not the focus of the story, rather it is Ezra’s downfall and final redemption that is deeply explored. However, while the two films differ greatly they share the related themes of redemption, family values, and the life of child soldiers.

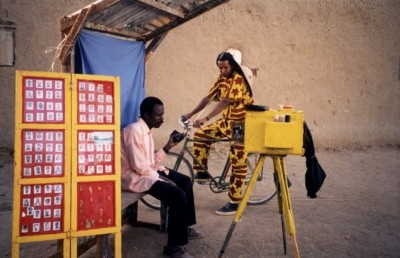

Ezra and Blood Diamond use a similar cinematographic style and art direction. Blood Diamond makes extensive use of hand held camera work, giving the story a chaotic feel and an uneasiness and discomfort that emphasizes the action. While Ezra also uses a significant amount of hand held camera work, the style does not relate as well thematically because it is not a high-tension film. In terms of art design, both films take place in Sierra Leone but were shot in cities and jungles in other parts of Africa. (One can assume that only viewers who have traveled to or lived in Sierra Leone will be in a position to argue with the accuracy of the country being represented.) Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, is portrayed in Blood Diamond as being hectic and intimidating. Danny Archer moves quickly through the crowded and dirty streets, often looking paranoically over his shoulder. The atmosphere portrayed is of an unsafe place rid with tension. Danny and Solomon leave the city during a violent outburst, running from gunfire and explosions. After fleeing the city the two main characters spend the majority of the film in the jungle. The rich natural colors –brown, green and red– are emphasized, bringing the locations to life. Ezra never ventures into the city but remains within the villages and the jungle of Sierra Leone. Ezra works within its means by creating very few elaborate lighting set-ups and using mainly natural light. The natural landscape of Rwanda, where the film was shot, was an adequate representation of the jungles of Sierra Leone. Both films use various techniques to portray different parts of the same country in a way that is believable and enables the viewer to become engaged in the story.

While Blood Diamond and Ezra share similar themes and cinematographic styles they vary greatly in their approach to the narrative. One of the major differences that separate the films is the development of the black African characters. In response to having his film compared to Blood Diamond, director Aduaka states in an interview for the Sunday Times Magazine: “His major characters are my minor characters, and my minor characters are his major characters.” In Blood Diamond Solomon’s character is essentially static throughout the film. Though he experiences numerous traumas, his character changes very little. With the exception of the evolution of his relationship with Danny Archer, the narrative does not make room for developing his character. Solomon is entirely focused on saving his son, and while it is a noble goal, his one-track mind leaves little room for growth. As well, in comparison to Archer, Solomon’s story is not as engaging or dynamic. This is problematic because the emphasis is therefore on connecting with the white character in a probable attempt to appeal to a broader (i.e. white) audience. In Ezra, however, the entire film revolves around the development of the title character, a young, black African man. The viewer witnesses his transformation from innocent child, to violent soldier, to guilt-stricken adolescent. Ezra has no white man as the counterpart to his character; there is no fabricated white man to help save the day.

There is a noticeable difference in acting between the Hollywood style in Blood Diamond and the less polished performances of the cast of Ezra. Although they speak English in Ezra, it is difficult to understand their speech due to the heavy accents and use of slang. While the slang adds to the authenticity, at times it makes it difficult to follow the dialogue. While the actors in Ezra are not as experienced as those in Blood Diamond –three of the main actors make their debut in ??Ezra??– they still deliver a powerful story. Whether or not the existence of Danny Archer is realistic and the portrayal of Solomon fair, their performances are riveting. DiCaprio and Hounsou are at the center of the drama and give exceptionally compelling interpretations of their roles. While the film borders on melodrama, it is a performance style which North American audiences are accustomed to –and which DiCaprio and Hounsou deliver without contrivance.

Despite Blood Diamond??’s advantages in terms of reaching the mainstream with its star power and big budget, the inclusion of certain Hollywood conventions weaken the overall impact of the story. For example, the incorporation of the idealistic white journalist, Maddy Bowen (Jennifer Connelly), had the potential to be a believable part of the story. Bowen, an attractive young American woman, helps Danny and Solomon throughout the film and eventually brings Solomon out of Africa. Although she is important to the story, the emphasis on the attraction between herself and Danny makes the existence of her character contrived, as her good deeds become a vehicle for that Hollywood constant: the love interest sub-plot. In contrast, ??Ezra is much more effective in its treatment of both white characters and women. The only white person to appear onscreen is a middle-aged white man trading drugs, arms and diamonds with the rebels. We never learn of his name nor his intentions. The white man is realistically portrayed as a necessary, but anonymous part of the story.

In addition, Ezra treats its female characters with comparable integrity. The women are present in the story to serve as more than just a love interest. The female characters are strong women who genuinely move the narrative forward by helping Ezra’s character take shape. Mariam (Mamusu Kallon) is a young rebel soldier with whom Ezra falls in love. Among all the young soldiers to whom we are introduced she is the only one who chooses to fight because of her ideals. She is also the only solider to openly criticize the brutality of the rebel army. Mariam has a connection with Ezra that allows her to influence his loyalty to the rebels, and question their intentions. Eventually Ezra’s love for their unborn child pushes him to desert the rebels in order to find safety and a new life for himself and Mariam.

The second supporting female character is Onitcha (Mariame N’Diaye), Ezra’s sister. Despite having watched her brother unknowingly murder their parents during a raid that ended in her tongue being cut out by other rebels, Onitcha stays loyal to Ezra. She helps him survive and eventually attempts to escape with him and Mariam. Throughout the Truth and Reconciliation Trial she is adamant about having Ezra know the truth about his actions no matter how painful the process. Onitcha and Mariam are essential not only to building the story but also to the character development in Ezra. They are credible characters with purpose beyond the obvious supporting role.

The narrative of both films also focus in part on exposing the truth behind child soldiers. Both films confront the fact that rebels kidnap children in order to turn them into combatants. By forcing the use of drugs and instilling fear in them the children are brainwashed into becoming violent, dehumanized killers. Blood Diamond resorts to graphic and explicit sequences to explain this truth. In one scene a group of small children must watch as Dia, who is blindfolded, is forced to fire a machine gun and kill a man. Dia’s loss of innocence happens so quickly it is difficult to stay connected to him. The overall process of the children’s transformation is shown in only a few scenes, leaving little opportunity for the audience to empathize with them. In addition, these scenes focus more on the grown men and the brutality they are inflicting on the children, rather than the children. The focus is on the violence being conducted, rather than the children’s reaction to the brutality. Ezra shows an identical transformation of the children but from a different point of view. Instead, Ezra focuses on how the child transforms as a result of the rebels’ torturous actions. Moments such as when the young boys quietly encourage one another to stay alive by following orders engages the viewer in the children’s progression. The portrayal of the horrific pre-raid ritual allows the viewer to see the final steps of the children’s transformation. The depiction is believable without being graphic. In an account found on the Child Soldier’s Organization of Sierra Leone official website, a boy from Sierra Leone describes this transformation:

They are sometimes between the ages of 4-14 years old and trained up in the bush and become very dangerous like wild animals. These children are given a chemical substance that’s their daily food during battle, it makes these children to be more and more dangerous like a bush fire in the harmattan” (Kuteh).

Ezra shows this process that turns young boys into crazed animals. One of the most powerful moments occurs when the young boys prepare to raid a village. First they are injected with a narcotic, and then they are gathered into a circle to dance around and chant while waving their guns in the air. Later in the film Ezra explains that this ritual puts the young boys in a trance, allowing them to commit horrific acts without being aware of their actions. Ezra focuses on how ritual is used to bring these children to the point where they are capable of raping, murdering and destroying. We are not exposed to one instant of extreme violence like in Blood Diamond, but are instead shown the details of the process that alters these young childrens’ consciousness.

Though violence is relevant to both narratives, each film displays it differently. Ezra uses violence to explain the trauma people underwent, while in Blood Diamond the violence is glorified in order to create effective action sequences (with excessive bloodshed being another convention of the Hollywood action film). In Blood Diamond nearly every action scene is filled with people suffering some sort of violent terror. Within the first five minutes of the film the rebels raid Solomon’s peaceful village. This scene is chaotic and does not focus on one person, but rather each shot is filled with villagers being chased down and shot at point blank. The cutting is rapid, yet nearly every shot shows someone being killed. When the rebels finish the raid, the remaining villagers are either taken prisoner and forced to search for diamonds or have an arm immediately amputated. In one close-up, a young boy’s arm is shown being hacked off with a machete. There are many such scenes which depict explicit violence. Gratuitous? Perhaps this extreme representation of violence is a result of audiences having become so desensitized to violence that in order to express the sheer brutality of the political violence Zwick felt it necessary to constantly bombard the viewer with terrifying images.

Ezra approaches violence from a different perspective by focusing more on the person committing the violent act than on the resulting mayhem. When Ezra is raiding his parent’s village the camera cuts several times to him screaming and stomping, terrifying people and preparing to kill. The actual murder of his family is never shown. It is not about shocking the audience with realistic images of violence, but rather demonstrating how a teenager can be brought to the point where he can kill without knowing or understanding why. It is also during this raid that Onicha has her tongue cut out by rebel soldiers. This horrific moment is not shown; instead the viewer is exposed to the aftermath and the trauma Onicha suffers. In turn, each film reveals dramatic truths about these brutal acts. Blood Diamond focuses on the actual violent act, and its shock value, while Ezra is concerned with the events leading up to the violence and its aftermath.

For films dealing with traumatic incidents (such as those depicted in Blood Diamond or Ezra) the ending is crucial to underscoring the final message. After two hours or so of violence, heartbreak, loss, and pain, what feelings and ideas should the audience be left with? Should they fear Africa? Should they embrace it? The respective conclusions of Blood Diamond and Ezra is what truly differentiates the films. The Hollywood ending is bitter-sweet but always heartwarming. An important lesson is learned and the good guys win. Danny Archer, the corrupt diamond trader turned sympathetic love interest, slowly bleeds to death at the top of a mountain while over looking a beautiful landscape of the jungle, reminding the viewer that there is something worth saving in Africa. With the help of Archer, Solomon is able to escape with his son and the priceless pink diamond. The beautiful and idealistic journalist, Maddy, helps Solomon bring his family out of Africa and to the United Kingdom, after which she writes a tell-all article exposing the major players of the “Blood Diamond” trade. Blood Diamond??’s solution is to leave Africa, to fix the problems from the outside. ??Blood Diamond allows the audience to easily digest the heartbreaking reality of how Sierra Leone is being exploited by the diamond industry.

Ezra leaves its viewer in a very different place. It offers no big resolutions or pre-packaged emotions. The ending is realistic and simple –it attempts to tell a truth. At the end of the film Ezra confronts the fact that he murdered his own parents. He reacts by standing in the courtroom and then immediately fainting. The ending of the film focuses on his final reaction, which is genuine, as opposed to some grand solution to his problems. Ezra may be more difficult for the average viewer because it does not give a precise conclusion. The viewer must think about where this film has taken them and why. There is no one to help Ezra escape from his life. Ezra must stay in Africa to confront his past and continue living, because leaving is not a realistic option. Ezra must try to rebuild his life in Africa, like so many others who have survived the atrocities of war.

While leaving an audience with questions as opposed to easy answers makes for a more effective political film, it does not necessarily increase a film’s exposure. Blood Diamond had the fortune of a big Hollywood budget, high-end promotion, and star power. These are factors that help a film become a box-office blockbuster and be seen by millions of people. Ezra must rely on a tight narrative, good performances, interesting camera work and film festival recognition to gain good reviews and hopefully increased exposure.

Although these two films are similar in theme and story, they differ not only in approach but also in affect. While one may debate whether the goal of Blood Diamond is to entertain or inform, it is clear that the narrative relies heavily on explosive and shocking action sequences for audience impact. In contrast, as Aduaka stated in the Sunday Times Magazine, “Ezra is not about who is good, and who is bad, it’s about the effects of war.” Aduaka is concerned with accurately revealing the psychological trauma people have suffered. While Blood Diamond seeks to shock the audience regarding war in Africa, the priority of Ezra is to bring the viewer into an intimate world that will shake their view of humanity.

Filmography

Blood Diamond. Dir. Edward Zwick. Perf. Leonardo DiCaprio, Dijmon Hounsou., 2006

Ezra. Dir. Newton I. Aduaka. Perf. Mamoudu Turay Kamara, Mariame N’Diaye. 2007

Works Cited

“Aduaka, Newton (1966-)”. Screen Online. April 6, 2007.

Internet Movie Database. April 6, 2007.“??Blood Diamond??”.

“Cinema: The Real Blood Diamond Story”. Sunday People. July 9, 2007.

“Ezra”. Internet Movie Database. April 6, 2007.

Kuteh, Mohammed. “This is My Story”. Child Soldiers. April 6, 2007.

“Modern History of Sierra Leone”. Cry Free Town. April 6, 2007.