“What is a Good Translation?” Bazin Revisited

“There is no one realism, but many realisms. Every era seeks its own, meaning the technology and aesthetic which can best record, hold onto and recreate whatever we wish to retain of reality” (André Bazin, What is Cinema?, Timothy Barnard, Trans., 52).

If I replace the word ‘realism’ with ‘translation’ in the quote above, I can opportunistically invoke all the main points to follow in my review of this new translation of André Bazin’s What is Cinema? in succinct (if sheepish) fashion: translation, refinement, improvement, destiny, Bazin, and Barnard. But I’m jumping ahead of myself.

In my own humble opinion, the name André Bazin is still a force to reckon with. In fact, I’d go as far as say that Bazin is the single most important film analyst/critic/theorist in film history. I use the term ‘analyst/critic/theorist’ because Bazin’s writing was not easy to pigeonhole. He wrote in a pre-academic era, where film was not yet a university subject, therefore most of his writing was aimed at the intelligent film viewer as well as the film critic writing for journals and magazines. He was neither a rigorous theorist who aligned himself to a singular paradigm, but he was not averse to making generalized statements of a theoretical nature. Above all, he wrote (and very well) intelligent film criticism and analysis on a broad range of subjects and national cinemas. And, an important point often overlooked, his criticism was a reaction to what was happening around him. As Dudley Andrew notes in his foreword to the 2004 University of California reprinting of What is Cinema?: Volume 2, Bazin wrote extensively on Neorealism, not only because he loved the films and the new aesthetic of realism they inaugurated, but because they were frequently being shown in the Parisian theatres of the day. “There still exists no better treatment of neorealism than Bazin’s fourth French volume, because he felt out those films with alert antennae, measuring their novelty as well as their value. The sensitivity of this kind of writing cannot be matched in retrospective studies, no matter how thorough and responsible they may be” (Andrew, xiii). Although he is unjustly pigeonholed as an ‘idealist’ or a ‘non-political’ thinker, these criticisms fly in the face of the way Bazin actually lived his life and incorporated the social body into his larger project of film learning and teaching (the first real great ambassador of film, as I like to think of him). The inner workings of how Bazin’s intellectual upbringing was intertwined with the broader social currency of France in the 1940s and 1950s has already been brilliantly served by Dudley Andrew in his seminal critical biography, André Bazin. For anyone who wants to read my own account of this, I direct you to an earlier Offscreen special issue on Bazin. Perhaps Bazin is best known for his Cahiers du cinéma legacy, which includes the journal itself which he founded and ran from 1951 until his death in 1958, the subsequent nouvelle vague which grew from its core group of critics turned filmmakers (Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol, etc.), the ‘auteur theory,’ and the culture of critical debate initiated by the running feuds between Cahiers du cinéma and other contemporary French film magazines, most famously, the Leftist Positif, which began in 1952, and criticized Bazin and his journal at every turn, denouncing their concern of aesthetics, style and form over politics.

Bazin has a second legacy, which is the canonization of his primary writings in the curriculums of pretty much every film studies department in the western world. There isn’t a film studies student anywhere who can get through three years of undergraduate study without reading (or at least without having had to) at least one text by Bazin (and, truth be told, Sergei Eisenstein). Keeping track of Bazin’s writings is no easy task because he wrote prolifically for many journals, magazines and newspapers during his most productive period, including Cahiers du cinéma (of course), Parisien Libéré, L’Ecran Français, Esprit, and Le Temps Modernes. The best of these scattered writings (65 out of an estimated several thousand according to Dudley Andrew) were collected in the four volume French edition Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?, published in 1958 in Paris by Editions de Cerf running from 1958-1965. Then of course there are the several books that bear his name, which include, in English, Jean Renoir, Francois Truffaut, Ed.; W.W. Halsey II & William H. Simon, Trans., New York: Simon and Schuster, 1973, Orson Welles: A Critical View, New York: Harper and Row, 1978, French Cinema of the Occupation and Resistance: The Birth of a Critical Esthetic, Francois Truffaut, Ed., Stanley Hochman, Trans., New York: F. Ungar Pub. Co., 1981, The Cinema of Cruelty: From Buñuel to Hitchcock, Francois Truffaut, Ed.; Sabine d’Estrée, Trans., 1982, and Essays on Chaplin, Jean Bodon, Trans., Ed., New Haven, Conn.: University of New Haven Press, 1985. When it comes to his status in academia, the bulk of Bazin’s critical legacy in the English speaking world stems from the first (and up until now) only English translation of Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?, selected, edited, and translated by Hugh Gray into What is Cinema?: Volume 1 and What is Cinema?: Volume 2 by the University of California Press in 1967. The University of California Press published a reprinting of the What is Cinema?: Volume 1 & 2 in 2004, which was supplemented by an excellent foreword by Dudley Andrew –which explains and defends Bazin from the critical backlash against him in the 1970s right on through to the 1980s, something which Gray simply avoids– but with the same translation. Why the publishers did not take the opportunity to revisit the translation, or add other essays previously not included, is dumbfounding.

For anyone who is a native French reader, and is aware of the original French texts, the fact that Bazin’s legacy is partly built around this latter translation has a tinge of irony to it, because it has long been known that Gray’s translation, while serviceable, did not do complete justice to the style and subtlety of Bazin’s writing. Bazinian scholars, francophiles, students, and otherwise curious observers can rejoice in the knowledge that an alternative translation to Gray’s is finally available, at least in Canada, in the shape of What is Cinema?, translated and annotated by Timothy Barnard and published by, Montreal: Caboose (2009). And the results are staggering. In Gray’s first translation he selected twenty-six out of the sixty-five original French essays. For this new translation, Barnard has selected thirteen essays, three of which did not appear in the Gray translation: ‘On Jean Painlevé,’ ‘William Wyler, the Jansenist of Mise en Scène’ and ‘Monsieur Hulot and Time.’

The list of the essays contained in this new translation are as follows:

1) Ontology of the Photographic Image

2) The Myth of Total Cinema

3) On Jean Painlevé

4) An Introduction to the Chaplin Persona

5) Monsieur Hulot and Time

6) William Wyler, the Jansenist of Mise en Scène

7) Editing Prohibited

8) The Evolution of Film Language

9) For an Impure Cinema: In Defense of Adaptation

10) Diary of a Country Priest and the Robert Bresson Style

11) Theatre and Film (1)

12) Theatre and Film (2)

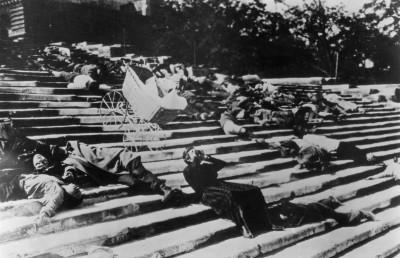

13) Cinematic Realism and the Italian School of the Liberation

As noted by translator/publisher Timothy Barnard in the foreword, some of the sixty-five essays that appeared in Qu’est-ce que le cinéma? were translated as they appeared in their original journal or magazine form, but some were abridged from their original length, and shorn of their footnotes, and others were substantially reworked by Bazin (most notably, ‘Ontology of the Photographic Image,’ ‘The Myth of Total Cinema,’ ‘Editing Prohibited,’ and ‘The Evolution of Film Language’). To this translation’s great credit (missing in the Gray volumes), the original source, along with any differences which may exist between it and the version translated in Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?, is duly noted at the end of each essay. The first eight essays chosen by Barnard are translated as they appeared in Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?, but for the latter five essays (all of which also appeared in the Gray edited volumes) Barnard has reverted back to the original essays for this translation, which makes them substantially different from the Gray versions not only in translation but in source. Barnard explains his reasoning for this decision: “Perhaps someday a critical edition of Bazin’s work can be published examining these different versions in detail, but for now decisions had to be made, and we thought it worthwhile to present these essays as they were first published, believing some of the discussions later excised to be stimulating and worthy of preservation. In some case, this has created places where Bazin’s ideas overlap from essay to essay, but this affords us a revealing glimpse of how he returned to his preferred themes, not to recycle his ideas or pad his essays but to take another run at his sometimes complex concepts” (ix).

It did not take long to notice the vast improvement in the translation. In fact, the first sentence. Here is the opening sentence of the opening essay, “Ontology of the Photographic Image” in Gray’s original translation: “If the plastic arts were put under psychoanalysis, the practice of embalming the dead might turn out to be a fundamental factor in their creation.” And the new translation, “If we were to psychoanalyze the visual arts, the practice of embalming might be seen as fundamental to their birth.” (My first thought was, what else would you embalm, the living???) On the surface not much of a difference, but the latter prose is more precise, forceful and closer to the original (“Une psychanalyse des arts plastiques pourrait considérer la pratique de l’embaumenent comme un fait fondamental de leur genése.”). Likewise in another passage a little later from the same essay, Bazin’s original sentence, “Mais elle ne pouvait que sublimer à l’usage d’une pensée logique ce besoin incoercible d’exorciser le temps” becomes in Gray’s translation, “Civilization cannot, however, entirely cast out the bogy of time.” In the new translation, “This parallel course, however, could only sublimate to rational thought, the irrepressible need to exorcise time.”

At times, the new translation is simply an improvement in prose style, coming much closer to Bazin’s original French (as in the latter quotes). For example, in the essay on Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest Bazin writes, “Si le Journal d’un curé campagne s’impose comme un chef-d’oeuvre avec une évidence quasi physique, s’il touche le ‘critique’ comme beaucoup de spectateurs naïfs, c’est d’abord parce qu’il atteint la sensibilité, sous les formes les plus élevée sans doute d’une sensibilité toute spirituelle, mais enfin plus le coeur que l’intelligence” (107). Gray’s translation resorts to some literal translations (‘l’intelligence’ becomes “the intelligence”) and clumsy terminology (“de spectateurs naïfs” becomes “the uncritical”) that (barely) captures the meaning but misses the style. Compare the two translations below for evidence:

Gray: “If The Diary of a Country Priest impresses us as a masterpiece, and this with an almost physical impact, if it moves the critic and the uncritical alike, it is primarily because of its power to stir the emotions, rather than the intelligence, at their highest level of sensitivity” (Volume 1, 125).

Barnard: “Robert Bresson’s Journal d’un curé de campagne (Diary of a Country Priest) almost physically compels recognition as a masterpiece, touching critics and unsophisticated viewers alike, because it touches our sensibilities—an elevated spiritual sensibility, no doubt, but in the end it speaks more to our hearts than to our minds” (138).

One does not even need to refer to the original French to see how much better the Barnard translation reads compared to the tortured and twisted Gray prose:

Gray: “Now if there is one and only one quality of the silent film irreconcilable of its very nature with sound, it is the syntactical subtlety of montage and expression in the playing of the film, that is to say that which proceeds in effect from the weakness of the silent film” (Volume 1, 138).

Barnard: “Now, if there was one aspect and one aspect alone of silent film to which sound was opposed, it was the syntactical subtlety of montage and expressionist acting. In other words, sound was opposed to the result of silent film’s infirmity” (153).

Gray also seems to have an aversion to using French terms that have been accepted in the English language. For example, when Bazin uses the term ‘trompe-l’oeil’, Gray replaces it with “a deception aimed at fooling they eye” (Volume 1, 12), whereas Barnard rightly, maintains the French word, which has a specific technical meaning relating to art history, which the Gray translation strips it from: (the new translation):

The dispute over realism in art derives from this misunderstanding, from the confusion between the aesthetic and the psychological—between true realism, which is a need to express the meaning of the world in its concrete aspects and in its essence, and the pseudo-realism of trompe l’oeil (or trompe l’esprit [f], which is content with the illusion of form. [2] This is why the art of the Middle Ages, for example, appears immune to this conflict: both violently realist and highly spiritual, it did not know the upheaval that technical possibilities have since introduced. Perspective was the original sin of Western painting.

This quote raises the interesting issue with regards Bazin’s position as a realist and his championing of the mise en scène/depth of field style. Whereas tromp l’oeil would appear to align with this film aesthetic, Bazin argues that it is not realistic (or is ‘pseudo-realistic’) because it is based on a technique dependent on human skill (and subjectivity), rather than the mechanical nature of the camera. The difference is one of degree: the camera may still be an illusion, but one that satisfies the human desire for that illusion, hence the gains toward realism are psychological. But, as Younger points out in his essay (Part 2) from this issue, “It is essential to emphasize the skeptical aspect of Bazin’s affirmations about psychology, his manifest awareness of human vulnerability to illusion and ideology. For Bazin, our receptivity to the world in which we live is inevitably conditioned by the desire we carry with us and by the ideologies that have shaped that desire.”

The new translation also catches subtle yet important errors. For example, in the famous concluding passages of ‘Ontology of the Photographic Image,’ Gray translates the following passage, which follows from the preceding paragraph’s discussion of the photograph’s relationship to nature, “Elle peut même le dépasser dans son puvoir créateur,” to “Photography can even surpass art in creative power.” The article “elle” does not refer to photography, but to nature, which gives the passage a completely different (and wrong) emphasis. The new translation corrects the error: “Nature can surpass even the artist in creative power.” This type of minor but significant correction occurs throughout the translation. In the essay on Chaplin there is an error, albeit minor, which even a non-Francophone would have spotted. Gray’s translation reads, “The public recognizes him [Chaplin] from his face and especially from his little trapezoidal moustache and his duck-like waddle rather than from his dress which, here again, does not make the monk [my emphasis], (Volume 1, 144). Of course the new translation gets it right: “Audiences recognise him by sight, more by his little toothbrush moustache and funny waddle than by his clothes, which once again do not make the man [my emphasis]” (25).

Along similar technical lines, when Bazin uses the term ‘travelling avant’ or ‘travelling arrière’ (as in “The Evolution of Film Language”), Gray translates it to the ‘camera moves forward/back,’ while Barnard uses the correct cinematic/technical term, “a dolly forward/dolly back’ (96).

One of the most welcome and useful additions to this translation, especially for the Bazin scholar, is the section “Translator’s Notes,” which are a series of copious notes that correct previous errors (film title errors, wrong dates, incorrect sourcing, etc.), and identifies the published sources of previously uncited allusions made by Bazin in the original articles. These go beyond merely bibliographic data to include substantial annotations and, in some cases, detailed expansions on technical and analytical matters. For example, the term ‘découpage’ was translated by Gray as ‘editing’ or ‘cutting’ (as many other editors have done), which robs the term of its multilayered French specificity. In fact, in most cases of its French use découpage occurs before the editing process –a process which Barnard feels is encapsulated by Roger Leenhardt’s early (1936) reference to découpage being ‘in the filmmaker’s mind.’ (266). Barnard keeps the word in its original French, and devotes a lengthy twenty page notation (more an essay actually) to it in the context of the essay on William Wyler, in which he charts the critical evolution of its many uses. While others have struggled with this term, using ‘shooting script,’ ‘scene breakdown,’ ‘scene construction,’ among others, Barnard explains how Bazin, its most fervent user, understood the term: “In Bazin’s hands it became a concept referring to the process of organising the profilmic and visualising a film’s narrative and mise en scène—as always, before (or during) the shoot and thus quite apart from editing. Bazin refers to it in the present article [“William Wyler, the Jansenist of Mise en Scène”] as ‘the aesthetic of the relationship between shots’—as they are conceived, not as they are edited. (Elsewhere, he defines the term more prosaically as ‘composition and camera movement’” (264). After reading this long annotation, you will understand why, for example, in Bazin’s seminal essay “The Evolution of Film Language” Barnard keeps the term in the subheading “The Evolution of Découpage since the Advent of Talking Cinema” (whereas Gray changes it to “The Evolution of Editing”). And why, for Barnard, the reinstatement of the term découpage, in its proper nuanced meaning, is essential to a proper understanding of Bazin’s cinematic ideas. For any English reader wanting to understand découpage in all its varied meanings, you can start and end here.

The “Translator Notes” is the longest section in the book, running a staggering 61 pages (251-312). Barnard’s research for this section has unearthed some potentially fascinating nuggets for further research, one which he reveals in his foreword. In “Theatre and Film Part 2,” Barnard points our attention to a lengthy essay on the same subject (Film and Theatre) which Bazin quotes. The original source given by Bazin was author M. Rosenkrantz, published in 1937 in Esprit. Barnard corrects it on two fronts, the date was 1934, not 1937, and the author’s name is M Rozenkranz, not Rozenkrantz. More tantalizing is Barnard’s hypothesis that this name may have been a pseudonym for the German film and cultural critic Siegfried Kracauer, who was living in exile in France at that time. As Barnard writes, “If this is the case, it would constitute a fascinating point of contact between the two thinkers, credited as the principal exponents of a ‘realist’ film theory yet who make no mention of each other’s work” (xii). Since this finding was made only a few weeks before publication, Barnard did not have the time to delve into this issue further, but he hopes that an enterprising German Kracauer scholar will one day be able to get to the bottom of this intriguing mystery.

Another highlight of this new translation is the inclusion of Bazin’s essay on William Wyler, one of the best examples of sophisticated close formal analysis and style in all his writing (and indeed in anyone else’s). Although there already exists an English translation of this essay by Alain Piette, adapted and edited by Bert Cardullo, which appeared in New Orleans Review, Vol. 12, No. 4, Winter 1985, 47-59, the new translation is still especially welcome because of Barnard’s authoritative translator’s notes, and his reinstatement of the term découpage, in place of editing. For example, in the earlier translation the term continuité is translated to ‘shooting script,’ but Barnard notes, in translator note ‘y’ , that the term has a slightly different, more nuanced meaning in its French use, where it can refer to the “third in a series of five stages in script development which culminated with the shooting script….” (284). On top of the benefit of the translator notes, there is still a different feel between the Piette/Cardullo and Barnard translation, with the latter being more attuned to the nuances of the French meaning of filmic terms (most importantly, ‘découpage’ over ‘editing’); and, to my ears, a more forceful writing style. Compare, for example, the concluding sentence of both translations and see for yourself which reads stronger: Piette: “Nevertheless, there is probably not a single shot in Jezebel, The Little Foxes, or The Best Years of Our Lives that is not pure cinema” (59). Barnard: “And yet every shot, every minute, of Jezebel, The Little Foxes and The Best Years of Our Lives is pure cinema” (69).

The Wyler text marks the one small error (of the ‘brain freeze’ variety) that I have spotted in the new translation, in the following passage from the essay “William Wyler, the Jansenist of Mise en Scène,” where Bazin talks about the relationship between technology and shot lengths:

First of all, for fairly obvious technical reasons, the number of shots is generally lower in films of greater realism. Talking films, for example, have more [my emphasis] shots than silent films. Colour reduces the number of shots even further, and Roger Leenhardt, taking up a hypothesis of Georges Neveux, has argued fairly convincingly that 3D films will naturally revert to the number of scenes found in a Shakespeare play—around 50 (Barnard, 58).

I did not have access to the original French of this article, but the common sense reasoning of the argument would suggest that the ‘more’ should read ‘less’. This is corroborated by the earlier English translation by Piette/Cardullo, where the passage is translated as follows:

First, for rather evident technical reasons, the average number of shots in a film diminishes as a function of their realism, of the long take with respect for continuous time and unfragmented space. We know that talking films have fewer [my emphasis] shots than silent films (New Orleans Review, Vol. 12, No. 4, Winter 1985, 53).

Hence we can presume an error in Barnard’s translation, but this is the only such error I have come across in my single read through of the book. An impressive record indeed.

Rather than continue citing differences, corrections, and improvements between this new translation and previous ones, I leave this pleasure of discovery to the interested reader. Any English-reading Bazin scholar, or student familiar with his work, will be astonished with the improved legibility of the new translation, and perhaps experience a sense of ‘reading estrangement’ (the familiar made new) when encountering old classic texts made anew by either the new translation or passages added back from the original sources. For this reason I (especially) recommend this new ‘reading’ for anyone coming to Bazin for the first time. I suspect Bazin-philes will need no coaxing.

The new translation can be currently purchased through the publisher website, caboose. If in Toronto, it can be purchased in Pages bookstore, or through the Pages website.

Bibliography

Bazin, André. What is Cinema?: Volume 1. Hugh Gray, Translation, François Truffaut, Foreword, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967.

Bazin, André. What is Cinema?: Volume 2. Hugh Gray, Translation, François Truffaut, Foreword, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971.

Bazin, André. Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?, édition définitive, Les Editions du Cerf, 1975.

Bazin, André. What is Cinema?: Volume 2. Hugh Gray, Translation, François Truffaut, Foreword, Dudley Andrew, New Foreword, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971, Reprint, 2004.

Bazin, André. “William Wyler, the Jansenist of Mise en Scène,” Trans., Alain Piette, adapted and edited by Bert Cardullo, New Orleans Review, Vol. 12, No. 4, Winter 1985, 47-59.

Bazin, André. What is Cinema?, Timothy Barnard, Translation and Annotation, Montreal: caboose, 2009.