Colin Low, an Anglophone in Quebec

There exists a Canadian culture. For some, it is but a pale reflection of American culture. For my part I perceive it like a culture of the survival of the Northern Hemisphere and an affirmation of the virtues of frugality. Frugality not in the sense synonymous to poverty, but rather of pertinence. [1]

Colin Low

Without wanting to re-write the whole of Quebec’s cinematic history, we can, nevertheless, remember that the presence of Anglophone filmmakers has always been very important. [2] The impact of this presence has not always been measured, and in fact has been most often ignored. The phenomenon of “the two solitudes” is as true in the production of films as in cinema’s critical discourse.

Certainly the decision to install the National Film Board (NFB) in Montreal in 1956 greatly contributed to the presence of Anglophone filmmakers within the Montreal film community, of which was Colin Low, Westerner, was a member. Born in Cardston, Alberta in 1926, Low admits to not having learned much about the Franco-Canadian reality during his first twenty years; his passage in Ottawa (1945-1956) will not be of great help to him either. He will quickly become an Easterner in Montreal while working at NFB where Franco-Anglo convergences were already taking hold: “the National Film Board never received enough credit for being a sort of bridge between Quebec and the rest of the country.” [3]

Colin Low, by his body of work and actions, contributed to the creation of a Canadian cinema. [4] His thematic preoccupations and his stylistic choices are characteristic of the type of cinema being produced in Quebec and in Canada from the 50’s to the present day. Low occupies a particular place, not only within Canadian, but also within Quebec cinema; even if both these paths were somewhat parallel. To speak of Low is to broach a taboo subject, the influence of Anglophone filmmakers upon their French-Canadian colleagues invoked in a Jean-Pierre Lefebvre article published in _À la recherche d’une identité: renaissance d’un cinema d’auteur canadien-anglais: “It seems as though many English-Canadian filmmakers had provided to their French-Canadian colleagues, explosives, of which they were unaware of their power and that they had not imagined their cultural, social, political values.” [5]

To this day, Colin Low has collaborated on more than 200 productions, but for the purposes of this study, we will limit ourselves to a particular chronological perspective (from the 50’s to the 2000’s) to two specific films, Capitale de l’Or (City of Gold, 1957) and Moving Picture (2000) and to his Fogo Island project made for “Challenge for Change” (1967-1970). Low, who was formed at the NFB school, is a documentarian first and foremost, and it is as a documentarian that his work has close links to the history of Quebec cinema, like two solitudes answering each other; one being the mirror of the other without being perceived too clearly by either.

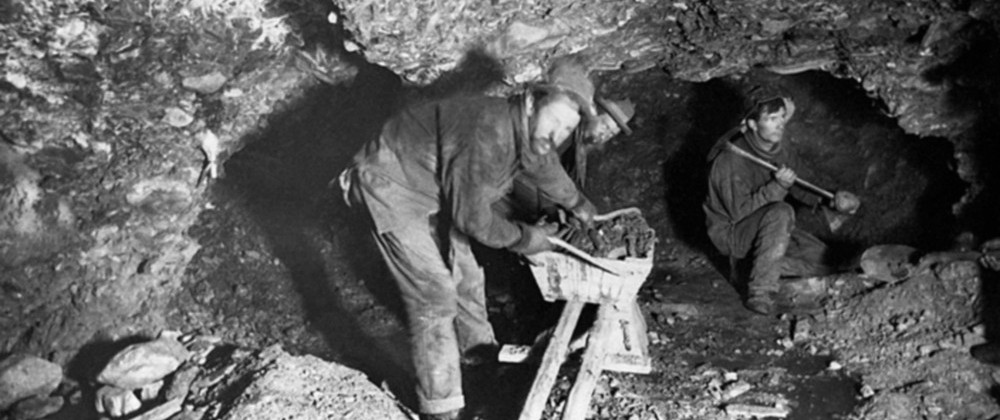

Capitale de l’or (City of Gold, 1957) and Quebec cinema

Already in 1987, within a colloquium that reunited for the first (and last) time, The Quebec Film Studies Association and its English-Canadian equivalent, I presented a “rapprochement” between our two solitudes entitled: “Colin Low and Pierre Perrault: Points of Convergence” [6], comparing Capitale de l’or and Pour la suite du Monde (1963). Colin Low spoke of the Dawson pioneers during the 1898 gold rush while Perrault spoke of the “Isle-aux-Coudres” pioneers who were attempting to revive porpoise fishing. It concerns two collective adventures within two microcosms, Dawson for English-Canada and L’Isle-aux-Coudres for French-Canada. These two filmmakers, nationalists from two distinct nations who do not know (or very little) of each other, seemingly had a common vision on the past, the present and the future of our respective dreams; in brief, on our survival. [7] In both films, the child characters are marginalised; they have games and different preoccupations than their elders. When one makes a film on the subject of memory, survival, deep-rootedness; it can be worrisome to notice that the children do not follow the same traces as their elders; a Western Canadian and a Quebecois had similar concerns.

An analysis of the stylistic choices of the two filmmakers reveals the same use of “language”. With Perrault, it is communicated via a direct cinema that listens to the voice and words of the protagonists; with Low, it is with an off-screen voice, a Grand Narrator, which unifies everything and renders it intelligible. The intelligible comes also from his work at the editing stage; the rhythm and, more fundamentally, the framing. Colin Low accepts the NFBism order of things, but surpasses it, while Perrault resists it. Low chooses a more out of hand universal language, much more classical; Perrault prefers to use a more personal filmic language which is more risky. By joining the thematic and stylistic aspects, we could conclude: “Colin Low looks for reconciliations (father/son and filmmaker/audience). Pierre Perrault prefers a “critical dialogue”(father/son and filmmaker/audience).” [8]

Colin Low and Quebec cinema in General

If there was and still is a barrier between the two solitudes, there are, nevertheless, individuals, films that prove some convergence exists. If the case of Colin Low is exemplary, it is not unique.

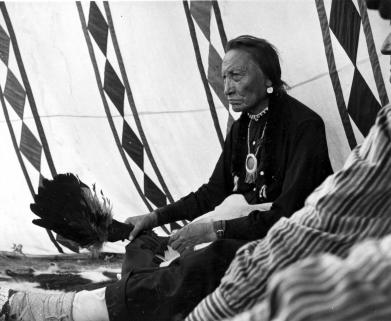

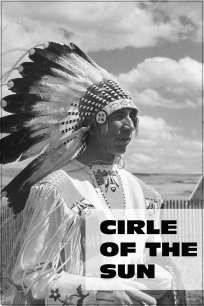

In many of his films, Low uses a thematic network that we will find in many Quebec films: the themes of survival, memory and the quest for identity. He also uses a stylistic which is close to that of Quebec cinema: a certain look that permits a discovery, often heavy, but sympathetic of the milieu. When Colin Low tells us that with Capitale de l’or, he “started to look at his images through their eyes” [9], the eyes of the Dawson pioneers, he effects a similar approach to that of the Quebec filmmakers for whom the revolution of cinéma direct* consisted to place oneself in the point of view of the people being filmed; of having a very strong empathetic rapport with representatives of Quebec populace. Low also expressed this empathetic rapport in Circle of the Sun (Le soleil perdu, 1960) by sharing the “Black Foot” Indians’ worries of the possible disappearance of their yearly Sun Dance. In 1982’s Standing Alone, he finds the principal character from Le soleil perdu again, Pete Standing Alone, still torn between two cultures and struggling with anxiety about survival. In The Hutterites, 1963, he presents the cultural vacuum that exists between a religious community and an environmental society; Low is said to be of the minority group, but very strong spiritually; Low shares values with all these groups, values of tenacity, of courage, perseverance and affirmation.

Circle of the Sun

In his first ethnographic films, he takes sides in his own way. Although his approach is very stylised, personal, even poetic, he makes “useful” films. The success of Capitale de l’or will lead to the rediscovery of Dawson city, to which governments will lend their support and promotion. With Le soleil perdu, he allows us to see the Natives in a different way: not exotic and very anti-Hollywood. Low had already manifested this direct approach in 1954 with the film Corral.

Corral (1954) and Quebec cinema

Corral is a film about Low’s childhood. “With this film I wanted to finally talk about the thing I most like, my childhood in Alberta.” [10] The universe of the Cochrane ranch, the horses, and of his father and grandfather’s horses. The horse trainer Wally Jensen shows his know-how by choosing to tame, from the middle of a herd, a restless animal, and succeeds in mounting the horse and letting it gallop across the fields until exhausted. For the subject to emerge in all its authenticity it took a real knowledge and sense of profound love. But it is the technical constraints of the time (the impossibility of filming with direct sound) and the artistic choices that give the film its character of originality and authenticity. Corral is a free film, frugal, as Low would say, without the omniscient voice-over narration typical of the Post World War2 NFB documentary. Low chose to film the universe of a ranch and in particular, the relationship between man/horse with rigor and honesty. Corral is a simple film, but simplicity is not synonymous with ease.

In challenging the tradition Griersonian documentary, Corral practically announced the cinéma direct which would largely consume the first Francophone group of filmmakers at the NFB from 1958-1964. At that time, Anglophones like Low, encouraged by producer Tom Daly and friends like Wolf Koenig, Roman Kroitor and Terence McCartney-Filgate, triggered a little revolution which preceded and hence inspired that initiated by the first Francophone team at the NFB (Michel Brault, Gilles Groulx, Claude Jutra, Bernard Gosselin, Pierre Perrault, etc.). It was the Anglophones, and principally McCartney-Filgate and Roman Kroitor who inaugurated the candid eye experience, prelude to the cinéma direct of the Francophone cinéastes. If Lonely Boy is the apex of the path taken by the Anglophone filmmakers then Corral, made much earlier, is its grand precursor. To properly reveal the reality of the cavalier Wally Jensen, or of the ‘lonely boy’ Paul Anka, required a certain deployment of cinematographic means, as Low said, of frugality and relevance. It also required a certain gaze, even a certain philosophy of life and of cinéma. With Low, these cavalier figures are essentially good; in promoting their values the films defend positive social values while attacking bad social values. Such vocabulary might seem inappropriate, but wholly fitting for a Mormon son. An aesthetic is often inspired by an ethic, and this is certainly the case with the cinéma of Low.

The “Newfoundland Project” (1967-1970) and the cinéma québécois

This ethic of social relevance will be expressed to an even greater advantage in Low’s “Newfoundland Project.” This project represents the most important manifestation of the Anglophone “Challenge for Change” program, which was initiated by Low. “We were inspired by Raymond Garceau’s work on the Gaspe region,” in Colin Low’s reference to the twenty-six films produced as part of the ARDA (Research and Development for Rural Agriculture) series (1965-1966). Cinéma was placed in the service of social action. They spoke of cinéma as a ‘tool.’ This process required the recognition of film as a product of a collective. The director is no longer the “auteur” (with capital A), but one of the artisans in the production thread. The people being filmed intervened directly in the creative process with the filmmaking team. And it is precisely this point of view that has been lauded by a great number of filmmakers of the Francophone Unit of the NFB, many of whom decided to resolutely follow this path. For example, Jacques Leduc or Fernand Dansereau who, with his series of twenty-seven films about St-Jérome, made cinéma as social intervention. At the same time, Colin Low was himself responsible for a series of twenty-seven films dealing with the social and economic problems of the inhabitants of the Fogo Island near Newfoundland, under the banner “The Newfoundland Project.” Both Low and Dansereau made cinéma to animate social action. Low relates, “Recently I gave some workshops in cinéma as social action with Fernand Dansereau.” Their parallel projects resembled each other enormously, because these two filmmakers shared the same desire for social change and the creation of a distinct national cinéma, which defined itself by its social utility and regionalist engagement.

I have had the opportunity to see four of the short films in the “Newfoundland Project.” The ties with Pierre Perrault’s L’Ile-aux-Coudres trilogy are even more perceptible in these films. In effect, with this series of films on the inhabitants of Fogo Island we find themes, characters, and a use of the spoken word which recalls the films of Perrault. The equivalents of Perrault’s Tremblay or Harvey are named Billy Crane (Billy Crane Moves Away, 1967), or Jim Decker (Jim Decker Builds a Longliner, 1967). Like Perrault, who with Pour la suite du monde resuscitated the hunt for the Beluga whale, Low, with his project, takes the initiative to create a co-op for the fishermen (The Founding of the Co-operatives, 1967). In this sense Perrault and Low demonstrate their lineage with the great Robert Flaherty, who would often provoke the proto-reality he was to film. On this same subject Low explains himself by saying that he would allow himself to “[…]initiate an activity which could then become autonomous. The more this step is controlled by the people concerned, the less it is controlled by outside observers, the better the results will be.” [11] At the beginning of the film The Founding of the Co-operatives, a title card reads, “The team of fishermen of Fogo Island have always worked together to confront the seasons and the elements. Can they stand together today to face another kind of adversity?” The answer, as you may have you guessed, is that a large group of fishermen will create the cooperative. And, within the cooperative, five years later, twenty-three long-haul boats will be built. “Thirty-five years later, in the summer of 2002, I returned to the Fogo Island to confirm that the co-operative is still going strong.” The goal of using “The Newfoundland Project” to create a cooperative of fishermen so that they can then continue the project and escape the poverty of the small region of Fogo Island proved a success. With his films on the region of St-Jérome, Ferdand Dansereau also succeeded in intervening as a social agent to help the people help themselves. In his case it was done by acting on the electoral process to obtain candidates in the mayorial election who were more favorable to social change.

In the film Jim Decker Builds a Longliner we find similar preoccupations to those expressed in Perrault’s Les voitures d’eau (1968): the fishermen discuss the future of their industry and the motivation to create a new, bigger boat that will help them survive economically. Low, as Perrault, is concerned in concrete terms with the “pursuit of the world” of a breed of fast disappearing pioneers. In Billy Crane Moves Away,” a traditional fishermen thinks seriously of moving to Toronto if he does not find the means of continuing his livelihood. And, at several points in the film, there are inserts of children watching and listening to Billy without much grasp of what is exactly happening. In the Jim Decker Builds a Longliner there are also shots of children who help in the construction of the long haul; and in the final scene they are the ones who are in the boat when the politician comes for the official launch.

In Children of Fogo Island (1967), a film like Corral, without dialogue, Low captures the reactions of the children in face of the social changes lived by the adults. In parallel and in the margins, the children play, as they did in Capitale de l’or (City of Gold). “I systematically asked my camera operators to film the children all during the shoot, in the hope that, in the end, the film would feel as if it were from the point of view of the children.” Like Corral and Capitale de l’or, Children of Fogo Island is a film of great poetry with many symbolic images (abandoned cars and old boats, children building oars, log cabins, small boats; images of the sea and waves that crash incessantly). “As far as I am concerned, Children of Fogo Island is the best film of the series.” It is understood that this great master of the traditional documentary, and cinéma of social intervention, is primarily someone who is sensitive to others, to those he films. He loves to make us love; cinéma as an art of the encounter, in the sense that this word has for individualist philosophers. This is also true of a majority of Francophone filmmakers at the NFB during the 1960s. At that time, Perrault said, we must “see the interior.” [12]

Children of Fogo Island

Labyrinth (1967-1980) and the cinéma québécois

Today, Colin Low’s name is largely associated with his research on large format screens, which led to the creation of Imax and Omnimax. Already, as a young animator in 1947, Low saw drawings by Norman McLaren which created 3-D effects. Colin Low told me, “From 1962, Roman Kroitor spoke to me about mounting a multiple screen project.” Remember that Low had already worked, with Kroitor, on three works of popular science: Time and Terrain (1948), The Romance of Transportation in Canada (1952) and Universe (1960). On his own, Low had also achieved Riches of the Earth and A Thousand Million Years (1954), and had been a keynote speaker at the “City of Knowledge”, in 1964. These didactic and scientific concerns can be seen throughout his work. The “Labyrinth Project” is situated in this perspective.

The Romance of Transportation in Canada

Therefore, Low and Kroitor wanting to try new experiences, put an end to the period of the candid eye and the cinéma direct, such as the “Challenge for Change,” which ended to Low’s satisfaction. Hence, with Kroitor, Low wanted to convince Guy Roberge, Canadian Commissioner of Cinematography, and Jean Drapeau, the major of Montréal, to allow them to take part in Expo 1967, which was to showcase an explosion of multiple screen projections. Several Canadian filmmakers made their contribution in terms of research and experimentation in various pavilions. Think of the Ontario Pavilion (Christopher Chapman and Barry Gordon), the film Evolution of Canada (“Budge” Crawley, Michel Brault, George Dunning, Claude Fournier). But it was the “Labyrinth Project,” under the tutelage of Low, assisted by Kroitor, which would have the greatest impact and longevity. Low was particularly responsible for the general design, the architecture, and the theatre constructed with three different venues. To occupy this new “labyrinth” Low organised a story based on the myth of Theseus. In 1979, the film In the Labyrinth, highlighting his work as an experimental filmmaker of the IMAX image and its “Labyrinth Project,” became available as a stand-alone film. In fact it is the film which was projected in one of the halls of the “Labyrinth Project”. As a consequence, Low became a specialist of universal exhibitions. It is also in 1986 that Low directed Transitions (co-directed with Tony Ianzelo) for the Vancouver Universal Exhibition, the first IMAX 3-D film. His great dream finally came to fruition: “I always wanted to do 3-D cinéma, even now I would like to remake Universe or Romance of Transportation in 3-D. In 1992, as part of the Universal Exposition of Seville, he made a film on IMAX in 3-D, Momentum; this time it signaled the first IMAX film in high definition (filmed at 48 frames per second).

Momentum was again a film without dialogue, which was a portrait of nature in Canada, of our winters in particular, but also a portrait of Canadian culture. In 1980 he filmed Atmos using the Omnimax technology. The film dealt with the climactic problems confronting our planet, our universe. Before Richard Desjardins, who investigated our boreal forest, but in synchronism with other films engaging the ecological battle, Low pursued his own trajectory while being in parallel with many Québécois documentarists. I am thinking in particular of the work of Maurice Bulbulian.

In 1988 Low directed, always for IMAX, his sole excursion into fiction, and also his only bilingual film [13], d’Urgence=Emergency. In this film the characters live as two solitudes (English, French). Félix St-Germain (played by Gilles Pelletier) suffers a heart attack and has to be rushed to the Montreal Cardiology Institute. During this time, through the use of parallel montage, we get to know a Native Canadian named Mary Diamond, who also has to transported urgently to the Neurological Institute, which is an Anglophone hospital. While travelling in the airplane transporting them to Montreal, our two protagonists talk, or at least attempt to talk with each other, to communicate despite the language barrier. At the end, Félix evokes the memory of Mary and remembers the role played by the airplane in their collective survival. Low adds a scientific element, employing images taken by a scanner and the inside view of a heart operation, aided by a catheter. Low’s ideas are perhaps best expressed through his use of popular science, but Canadian life, its Nordic sensibility and its linguistic and cultural diversity, are also well invoked.

There are few Québécois films that have launched themselves in similar technological experiences. We can note that films such as 24 Heures ou plus (Gilles Groulx, 1977) or Le dernier glacier (Jacques Leduc et Roger Frappier, 1985) use the frame within a frame, a form of multiple screens. These were socially and politically engaged films. The spirit of the French series New Society [14] was not far beyond. Would IMAX follow this path? Not really; even though Low himself has always used IMAX to serve his vision of the world, based on tolerance, a knowledge of others and the world, to better serve pedagogical interests. The images of Labyrinth are images of the world, a planet, a universe in crisis, he would say, with too many injustices. With his montage of multiple images, usually in five, which can be in communication with each other or be autonomous, Low puts in opposition our excessive riches and the unacceptable poverty of the Third World. The numerous images show the diversity of countries, rituals and beliefs, climates, etc., and helps us to understand the complexity of the world. Again we discover at the same time, Low the teacher and the humanist.

When asked about his experience with IMAX, Colin Low has often repeated to me that for him, even with his definitive interest in new technologies of image making, the moral preoccupations remained, to his eyes, the most important. Also, in 1999, with his accomplished experiences in new technology, Low returned to his past as a classical documentarist and proposed a reflection on the possibilities and limits of the image, those of the multiple screen cinéma. This interest led to what is presently his most recent film, Moving Images.

Moving Images (2000) and Us

The 1980s and 1990s were a time of reflection for Colin Low. In 1982, Low and Tom Daley collaborated for a last time on the film Standing Alone. Low revisits the universe of Circle of the Sun with the return of the character Pete (Standing Alone). Through Pete, Low examines the survival of ancestral values; Pete wonders whether the ritual of the Sun Dance will survive and if the children will understand its meaning. We can clearly see the abundance of themes common to Low’s cinéma. But these themes are also present in Québécois cinéma. We need only think of the Chronicle of the North-East Indians of Quebec by André Lamothe. Standing Alone is again, in part, a throwback to the ethic and aesthetics of Grierson: a film made by a gifted craftsman who respects his subject; who never makes a film for art’s sake, but uses the material (even a ready-made film) to propose a vision of the world that is useful to society, or that will be judged as such by society. On the other hand, from Circle of the Sun to Standing Alone we can chart an evolution, a transformation in documentary style at the NFB and in Canadian cinéma in general.

However, the film which is the most representative of this new documentary aesthetic, an almost crisis of the documentary (as was said at the time), is Moving Image. In reality, there are two films in Moving Image. The first, like a more traditional documentary, concerns the 17th century artist-engraver Jacques Callot. Low approaches the work of Callot “as a brilliant anticipation of the cinematographic art. As film-maker, Callot has an insatiable visual appetite, a regard for the acute, a sometimes fantastic realism […] writing and […] and filmic perspective: close-ups allowing the analysis of details which would remain unobserved.” [15] Moving Images uses Jacques Callot, a great artist of his century, protesting in his own way as a graphic illustrator of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). In the manner of Goya, his works were not only realist, nearly documentary, but also a gesture of protest against the war. Callot was an engaged artist, as was Colin Low his whole life. His work with the “Challenge for Change” is explicit in this regard, as well as his respect for the grand tradition of social documentary a la Grierson, Vertov or Ivens –which a certain Québécois cinéma was also, with more aplomb in the 1960s, partially eclipsed in the 1980s, followed by a slight return to form in more recent years.

There is also a second film in Moving Images, more subjective, which explains the spiritual, artistic and technical path of Low’s career, and the manner in which Callot is inscribed within this. Moving Images is the grand synthesis-film of Low’s oeuvre and of his vision of the world. It recalls the great moments in his personal life, his origins on an Alberta ranch, his formative years in art school, his arrival at the NFB and his decisive encounter with Norman McLaren, the “Labyrinth Project,” etc. Moving Images is therefore a film about a filmmaker who is making a film on the career of the filmmaker. A film about “I”, like much of the Québécois documentaries of the 1980 to 1990s, starting with the Journal inachevé, by Marilù Mallet (1982), the Voyage en Amérique avec un cheval emprunté, by Jean Chabot (1987), Chronique d’un temps flou by Sylvie Groulx (1988), up to the pioneer films like those of Anne Claire Poirier, Tu as crié: Let Me Go (1997) or, especially, Moi, j’me fais mon cinéma de Gilles Carle (1998).

The narration of the film, in its own image, is complex. There is a central narrator, who is Low himself. From the beginning he tells us, “There are people who may consider me an eccentric, possessed…I looked at and used thousands of images since I starting making films.” We can plainly see that the “I” is omnipresent; as it is more and more in the documentaries of young Québécois filmmakers. Colin Low has admitted to me many times that he does not like this form of cinéma: “I prefer the classic documentary and I think that sometimes the autobiographical format makes us lose a certain respect for the subject.” But this complexity could serve him well. Thus he invokes his childhood in Alberta, where horses played a major role: it is from this that his work will take shape, which he will then seek in multiple varied representations, such as Leonardo Da Vinci, Muybridge, or lesser known painters like Alfred Miller (Canadian, 19th century), Alfred Waugh (painter of the American Civil War).

In addition, Low integrates images from his own films, Corral, Universe, the “Labyrinth Project,” etc. Going back and forth between his life, his films, images from other films, and images of war to show how the technology of images, its evolution, is linked to a fascination with violent imagery. Low uses some engravings from the Encyclopedia of Diderot and demonstrates how, even today, they can be used to make guns, instruments of death.

We find this same level of narrative complexity in the best examples of Québécois documentary of the 1990s (Carlos Ferand, Visionaires, 1999, or Michel Langlois, Le fils cassé, 2002, etc.). With Moving Images, in a partially similar way, the old path gives us a great lesson on the universality of cinéma. First with its aim of presenting the vast subject of the representation of war, weaving parallels between Jacques Callot’s treatment of war and war imagery depicted across contemporary mass media. To accomplish this he uses a narrative that operates on several levels. A documentary which, in the rigor of its approach and complexity of form, shares a commonality with that which Québécois cinéma has better expressed through its feature fiction films (Denys Arcand, Claude Lauzon, Lea Pool), achieving, through form and meaning, a universality.

Conclusion

If in Moving Images, Low speaks to us of his interest for Leonard de Vinci, the Encyclopaedia of Diderot or for Jacques Callot, this tells us much about his cultural and spiritual world. Low is a Humanist in the classical sense of the term.Like Grierson or Rossellini. Like the majority of Québécois cinéastes, starting from Pierre Perrault. For each of these creators, the artist has, above all else, a social responsibility; and a self-defining function.

This question of identity spreads across all Canadian cinéma, not just Québécois cinéma (even if this interrogation takes on a more important dimension for a minority of Francophone directors in the vastly Anglophone North America). Both schools of Canadian cinéma, Anglophone and Francophone, want to assert their difference in face of the giant popular culture and cinéma of the United States. According to Low, we are all North Americans: “I do not think I am a naïve Canadian Nationalist or regionalist in the narrow sense. I come from the Western part of the country. I like to qualify myself as a North American realist.” [16] But, how then, does one discover their roots? For Low and for many Canadian and Québécois filmmakers, they find it in the country, the landscape, Nature, but also in childhood (individual and collective).

What becomes evident in Moving Images, as in most of Low’s films, is a sense of great anxiety, inquietude. In a sense of irony, someone who has dedicated his life to producing films intended to make individuals more tolerant, discovers that the same tools of his trade can help contribute to an opposite effect. Towards the end of the narration in Moving Images, Low says, “I am afraid that this technology will never be properly controlled.” So the inventor of multiple screens like “Labyrinth”, and IMAX, who has converted, as others, to the television documentary, but has always used these technologies to form a more conciliatory spectator in the face of others, now believes that these tools will find other functions. Low is aware of a crisis in the image, a crisis in representation, something that the cinéma of English-Canadian filmmakers Atom Egoyan and David Cronenberg have illustrated, but which the documentary cinéma of Low and other Francophone filmmakers from Quebec, have also expressed.

Through his films and written texts [17] Low has always defended a cinéma of honesty. “The tradition of the NFB developed out of a respect for the subject of its documentary. We work –with few exceptions– in collaboration with the subject and within the limits imposed by the subject. We have no use for commercial or political mythology.” [18] The “we” Low refers to applies to both Anglophone and Francophone filmmakers.

The two groups (Anglophone and Francophone filmmakers ) share a mixture of utopia, prophecy, social preoccupation, but also poetry. The two groups of artists want to create a language that is properly Canadian but also universal. Low incarnates this to perfection. It is a role model to follow, and many have. Also, as a producer, Low has been a spiritual “father” for numerous Anglophone filmmakers who have enriched Canadian and Québécois cinéma. In the field of animation he helped Arthur Lipsett, Derek Lamb, and Gerald Potterton; he produced the “Challenge for Change” series for women and, in that context, produced films by Dorothy Hénaut and Kathleen Shannon; on the side of men, he produced the first films of Tony Ianzelo, Giles Walker, and John Smith. Low has contributed in creating a new, diversified English-Canadian cinéma in Quebec. [19]

Low embodied, as he wished, a cinéma of frugality and pertinence. These are values and principles of filmmaking which can stand for all Canadian filmmakers. But, as the North Pole and the South Pole are alike without ever being able to meet, the cinéma of Low (and by extension the cinéma of Anglophone filmmakers in Quebec), while maintaining many similarities with our own Francophone cinéma, remains in parallel, in the margins.

*Francophone filmmakers in Quebec used the term ‘cinéma direct’ in reference to their work. In Anglophone critical discourse there is usually a different distinction used, with ‘Direct Cinéma” used to define the English documentary filmmakers from the US and Canada. The term is defined by a more ‘objective’ non-interventionist approach, a ‘fly-on-the-wall’ philosophy. In contrast, the French documentary filmmakers from France and Quebec are referred to as ‘cinéma vérite’ and implies a more sympathetic (and sometimes ironic and self-deprecating) bond between the filmmaker and subject, a more ‘interventionist’ attitude. Hence, where Pageau uses ‘cinéma direct’ you may find these same French filmmakers referred to in English discourse as ‘cinéma vérite’ and Low and co. as ‘direct cinéma’. (editor, Donato Totaro)

This essay first appeared in its original French as “Colin Low, un anglophone au Québec,” in Le Cinéma au Québec: tradition et modernité under the direction of Stéphane-Albert Boulais, Montréal: Fides, “Archives des lettres canadiennes.” Published by the Centre de recherche en civilsation canadienne-française de l’Université d’Ottawa,” tome XIII, 2006, 349 pages.

Translated from its original French by Mark Penny and Donato Totaro

Endnotes

1 Speech delivered during the screenings devoted to the NFB on its 50th anniversary, by the Director’s Guild of America, December 8, 1988, in Los Angeles.

2 In the Dictionary of Quebec Cinema by Michel Coulombe and Marcel Jean (Montreal, Boreal, 1999) we can identify more than 60 entries relating to the Anglophone presence in Quebec.

3 “The Film Board has never been given the proper credit it deserves as a kind of cultural bridge between Quebec and the rest of the country.” (Colin Low (2000), “Interview,” Take One, no 24 (Winter), p. 32. Interview by Wyndham Wise and Marc Glassman). In a text published following this interview and which is entitled “Some Thoughts on the Future of the Film Board,” Low added: “The NFB was a bridge between two solitudes”(the NFB has constructed a bridge between the two solitudes).

4 The value of Low’s work as been underlined and awarded by both communities: in 1996 he was named a Member of the Order of Canada, in recognition of his extraordinary contributions to cinema; in 1997 he received the Albert-Tessier Prize from the government of Quebec for the body of his work.

5 Jean Pierre Lefebvre (1991), “Les cinémas canadiens: d’une image à l’autre,” in Pierre Véronneau (dir.), À la recherche d’une identité: renaissance du cinéma d’auteur canadien-anglais, Cinémathèque québécoise, p. 24. The body of work visited by Lefebvre is principally the NFB of the 1950s to 1960s.

6 Pierre Pageau (1987), “Colin Low et Pierre Perrault: points de convergences,” in Pierre Véronneau, Michael Dorland and Seth Feldman (dir.), Dialogue: cinéma canadien et québécois, Montréal, Mediatexte Publications Inc. et Cinémathèque québécoise, p. 139-151.

7 Jean Pierre Lefebvre (1963), “Colin Low, poète de la survivance,” Objectif, nos 23-24 (October-November), p. 24-37.

8 Op. cit., p. 150.

9 Colin Low (1996), “Capitale de l’or et Ile Fogo: le documentaire comme outil de communication et catalyseur de changement social,” in Catherine Saouter, Le documentaire: contestation et propagande, Montréal, XYZ éditeur, p. 65. French translation of the communication made in the framework of the Pegram Lectures, 1972. I consulted the original archives of the Pegram Lectures at the NFB Documentation center, and can attest that the translation is not very good and, most importantly, that in these readings Colin Low has done considerable theoretical work (over 200 pages), with a large section entitled “Media as a Mirror”; this work shows that for Low, and other followers of Grierson, the cinema can not be made or conceived outside of social action.

10 Colin Low, interview by tape recorder by Pierre Pageau during January and February 2003, translated to English by Pierre Pageau. All citations by Low without reference are extracts from this interview.

11 Saouter, op. cit., p. 70.

12 Pierre Perrault (1970), Pierre Perrault, Cinéastes du Québec, no 5, Montréal, Conseil québécois pour la diffusion du cinéma. Perrault adds, “It is a question of knowing in the global sense of the word and not to give the illusion of seeing or being distracted[…] And cinema has allowed me to draw my knowledge from the very sources I am pretending to explore.”

13 Prior to 1960, we can also cite a similar case, that of the celebrated bilingual film by Gordon Sparling (1934), Rhapsody in Two Languages, which poked fun at our linguistic “two solitudes.” Sparling was also an important member of the Associated Screen News, which was a noteworthy production-distribution organism in Quebec of the pre-1950s. Gilles Carles also amused himself in this game with his film Stereo (1970).

14 New Society is the French version of the “Challenge for Change” program (of which Low was one of the creators and vital contributors). “With the New Society project (1969-1979), which was undertaken as part of a program to fight poverty, another dimension was added: social activity” (Le dictionnaire du cinéma québécois, op.cit., article on NFB, by Pierre Véronneau, p. 480).

15 Georges Sadoul (1969), Jacques Callot, mirror de son temps Paris, Gallimard.

16 Colin Low (1992), “Terre à vendre,” Lumières, no. 31 (summer), p. 42. Extract of a speech given at a meeting on Canadian Cinema at Saint-Étienne, in 1983.

17 Like Grierson and Perrault, Low published numerous writing on cinema. A study on Low’s cinematic thoughts would reveal what his films have already said. Jacques Aumont, in a recent work on engaged filmmaker-theorists, wrote the following: “[…] the cinema can help in the fabrication of an ideal society, of a community of humans who, at least in a certain extent, would escape pettiness, limitations, the harshness of society, exploitation, and tyranny. In short, there has always been in the ideological thinking of filmmakers, the desire for utopia,” Jacques Aumont (2002), Les théories des cinéastes, Paris, Nathan Cinéma, p. 104.

18 Colin Low, “Terre à vendre,” loc. cit, p. 45. In the text “Some Thoughts on the Future of the Film Board,” loc. cit, Low adds: “[…] The NFB made Canada a kind of gentler culture than the American’s…”.

19 Moreover, many of these filmmakers are cited in the article by Isabelle Juneau, “The new Anglo-Quebec film,” À la recherche d’une identité: renaissance du cinéma d’auteur canadien-anglais, loc. cit., p. 95-11.