Incest and the Isolation of Country Life: Beautiful Kate, a film by Rachel Ward

A story more frightening for being somewhat mundane

Beautiful Kate, directed by Rachel Ward

Based on a book by Newton Thornburg, adapted by Rachel Ward

Production Designer Ian Jobson

Cinematographer Andrew Commis

Editor Veronica Jenet

Screen Australia, 2009; Entertainment One, 2010

How did a beautiful girl end up dead on the road, and her brother hanging from the rafters in the barn? It is a mystery. The film Beautiful Kate starts with a young woman and an older man, an actress-waitress and her writer lover, a couple engaged to be married, Toni and Ned, on a trip to his family home in south Australia to visit his sick father, Bruce, and caretaking younger sister, Sally. “Good morning beautiful, my beautiful,” the writer Ned says to the young woman, Toni, a greeting she thinks makes him sound like her grandfather (it is, really, the difference between a writer’s sensibility and that of an ordinary enraptured man; and, also, a suggestion of an inappropriate relationship between a man and a woman). Ned and Toni drive through a winding road in a valley with mountainous hills beyond, a beautiful image, one of many, but in the dark night, driving, they hit a kangaroo, one of several road-travel mishaps in the film. The accident is a jolt, and not the only one. There are pleasing things in the film ??Beautiful Kate??—the location and photography, the writing and acting, but it is a film that can be disturbing to watch: there is complexity and love twisted into perversity at its core, and though elegant, intelligent, and poetic, it is a film of fear, rage, and shame, of lust and vengeance: it is a horror film.

When the couple, the young woman, Toni, and her older lover, Ned, arrive during the night at his family’s old house, the young woman asks if this is what they drove all that long way for. His sister, Sally, welcomes him, but looks surprised and askance at the young woman with him (Toni seems not to have brought a case of clothes and Ned explains that she’s an actress and actresses do not wear clothes). Of course, they did not arrive for the house, but to see the old man, Ned’s father Bruce, a tough old man—both honest and jeering—still haunted by the death of two of his children, his oldest son Cliff and Ned’s twin, Kate. The film is full of Ned’s memories of his youth on the family farm and his memories of Kate, though when his father Bruce asks if Ned remembers her, if Ned hears Kate’s voice as the father does, Ned denies it.

Ned, Bruce, Sally and Toni

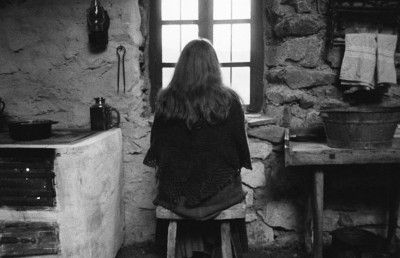

It is hard to describe country life for those who do not know it. There is daily beauty and boredom, and hard work and questions about deep purpose, and distant but known and seemingly friendly neighbors and old communal resentments, and all kinds of nature—and it is strange to be a young person growing up in isolation, not sure of what is normal or queer, especially where matters of sex are concerned (the relationships between parents are usually private, and the illustrations provided by farm animals are more diverse than most people recognize or acknowledge). Living in isolation, and feeling sexual, to whom does your attention turn? The film Beautiful Kate shows some of that beauty and isolation and confusion; and little things—such as a jar of vapor rub—bring back memories for Ned. Ned recalls his sister Kate’s scatological joke, presenting a jar of vapor rub as a moist butthole, and Ned initiates sex with Toni; a connection that augurs further revelations. Ben Mendelsohn as Ned has an intelligent but tormented, weary face. Maeve Dermody as Toni is sensual, fun-loving, decent, but immature, which does not mean that she is incapable of recognizing or responding to the truth. Rachel Griffiths as Sally, Ned’s younger sister, first looks plain—and then one realizes that she is pretty but worn down (Sally takes care of her father and also works in an aboriginal clinic).

The next day, on the morning after Ned and Toni’s nighttime arrival, they go in the father’s room for a visit, and he, Bruce (Bryan Brown), rudely greets his son, asking if Ned’s South American heiress has given him up, having gotten his number—having come to know him—like all his previous women. The father says he has heart disease and accepts that he is dying. When several of them sit at the table for breakfast, Toni goes through a photograph album and asks, “Who is this?” The father says it is his daughter; and Toni says she, Kate, is beautiful. Ned recalls Kate with a rifle shooting at sheep on the farm. We learn then that Kate was his twin, though they were not identical; and Ned will tell Toni that Kate died in a car accident, and that his brother did too (though we are allowed to see Ned’s memory of his brother Cliff hanging in the barn, a suicide). The father says Ned could have been a famous writer by now, except his distracting weakness was “cunt.” Ned laughs at what seems the truth. When Ned wakes at night, and goes for a drink from the fridge, he hears a noise, but does not know that it is his father crying; and after going into the schoolroom-office, where he and his siblings were home-schooled, and finding in a desk a prize won in childhood, a prize the father had not valued, the writer takes out a yellow pad and begins to write (he mentions his brother’s suicide, and a trail of wounds). Hours pass and the sister, Sally, goes to work at the clinic, and when Bruce interrupts him and Ned says he is working—Bruce queries, Work?—Ned reminds his father he is a writer (alas: something other writers must do as well). Bruce mentions the filthiness of Ned’s writing before he says they never talked about the last summer the children had together. There are things the father does not know or understand. It is fascinating, though inevitable, to think that the father, ever so critical, created a family that contains secrets that are beyond him; but, then again, certain secrets are beyond almost everyone.

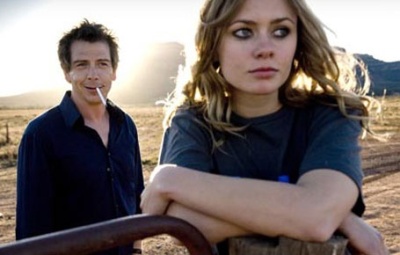

Ben Mendehlson as Ned and Maeve Dermody as Toni

After the girlfriend, Toni, tries out the backyard bull—a large can held up on moving ropes—and is allowed by Ned to fall, an allowance that could be a reflection of his basic indifference, Toni asks Sally if she likes being everyone’s slave, and asks if Sally does not want to leave them—the father and the son—alone. Sally says they might kill each other, and Toni says she would risk it. Sally then announces to Ned that she is going away for a few days. With Sally gone, Ned is the primary caretaker, but he continues to write, and when Toni interrupts him, Ned says, “I’m trying to write,” but Toni answers, “I don’t know why you bother—no one reads anymore.” They begin to have sexual intercourse, standing up, with him entering her from behind, as is his habit (a denial of her face, of her identity?—allowing Ned to imagine someone else?). “Do you love me?” asks Toni. “I’m marrying you, aren’t I?” he answers.

Toni can seem foolish, involved with the wrong man, out of her depth—but her instincts are sound and when we see her response to Bruce, we see another aspect of her character. Left alone, Bruce falls and wets himself, and Toni comes in, lifts him onto the bed, and places a large towel over his groin before changing his pajamas, demonstrating strength and a concern for the dignity of another person that we might not have guessed. The father asks why a girl like her is involved with an older man; it is an honest question as well as a malicious one—it is easy to see he is sabotaging his son. Bruce tells Toni she should be in Hollywood, and she admits she is thinking of that. “Youth is beauty, and beauty is youth,” Bruce says.

Ned remembers seeing “beautiful” Kate (played by Sophie Lowe) in the bathroom, her breasts exposed, putting on vapor rub; and Ned watches her then—and she reprimands him (young Ned, Scott O’Donnell). Kate then goes into Ned’s bedroom, looking out the window at farm life and commenting what a waste it seems for a calf to turn into an old cow, another iteration of the thought that youth is beauty, before confiding to Ned that the vapor rub reminds Kate of their dead mother and that Kate misses her. Kate cries, and Ned tries to comfort her, caressing her, but he is sexually aroused and ejaculates. Decades later, while visiting his sick father, Ned makes the writer’s mistake of writing that memory down—and Toni discovers it and is repulsed and leaves him. Ned returns to his memory, when he hid in a shed in shame, and Kate came to him, saying, “Kiss and make up” and they kiss through a screen window (kiss and make up: here, an unfortunate ritual of forgiveness)—and then Ned leaves hiding and takes a water hose and wets Kate (something that can seem innocent and playful, or an obvious symbol of the male member and its ejaculation).

Human beings are given to all kinds of feelings, but not all of them are acted on; and there are different kinds of prohibition against some of them, such as the belief or sense that incestuous carnality destroys familial feeling as exists between siblings, or that breeding between close relatives destroys genes, producing extremely diseased or flawed bodies. The prohibitions are philosophical and physical. It seems unnatural for a brother and sister, a father and daughter, or a mother and son, to experience sexual attraction. If pursued, a nurturing or protective relationship can become dominating, exploitive, lascivious, unhealthy, one word and another for a form of evil. Without saying any of these things, Toni recoils from what Ned has lived, remembered, and written, and the average film viewer finds her response easy to understand.

After Toni reads Ned’s notes about Kate and disgustedly leaves, Ned accuses Bruce of paying for the cab that took Toni away, and accuses Bruce of killing Ned’s brother Cliff—of driving him to suicide with criticism and pressure—and Ned says he might kill Bruce just for the pleasure of it, before getting in a car and following Toni’s cab, trying to get that car to stop. She gets away—and he gets out of his car and in the darkness screams, “I’m still here.” He could be screaming at the cosmos, at whatever god he believes in (with his brother Cliff and sister Kate gone, why is he still here?). The next morning, when Ned enters Bruce’s room with medicine, Bruce points a gun at him, remembering the previous night’s threat on his life. Ned apologizes, says he was drunk. Bruce says he never liked the feeling of being drunk, and Ned says he himself seems to like it, and Bruce says Ned always did—and that introduces another memory (the transitions in the film are direct, tight). We see the long-ago night when Ned came home drunk and went into the wet pond to relax and think before going into the house—the pond is now dry, during Ned’s visit to his sick father—and when the young, drunk Ned goes to the pond rather than the house, Kate goes out to find Ned; and Ned tells her he does not want her out there, to go back inside—but she insists on being with him, and that is when brother and sister, Ned and Kate, have sex. It is the honesty and simplicity of what happens between Ned and Kate that makes it so awful: it is the almost casual, shared devastation of two souls. An owl—sometimes seen as a symbol of wisdom, sometimes as a symbol of death—flies nearby and Kate sees it. Kate returns to the house, then Ned does; and the youngest sister Sally sits, playing with her food, unable to eat.

Sophie Lowe debut as Kate

Ned, who volunteers for work to get out of the house and away from Kate, does not understand how Kate can be cavalier about what happened. She (Sophie Lowe) is angry at his rejection of her and tells their older brother Cliff (Josh Macfarlane) that Ned (young Ned, Scott O’Donnell) tried to feel her up, an inexact admission, and false for its lack of completeness; and the two brothers fight (Ned insists on the fight; he wants to punish himself). Bruce commands Ned to take Kate to the town dance and then bring her home, but Kate is still trying to seduce him and Ned leaves the dance for a tryst with a local girl; and Kate leaves the dance with Cliff, and there is an accident on the road—and Kate dies, then the remorseful Cliff kills himself. The film presents one of the most damaged families ever seen on the screen, and it is more frightening for being somewhat mundane: upon immediately meeting and looking and listening to them, one would not guess the extent of the damage.

Ned puts his ill father in a wheelchair and takes him for a stroll near the dry pond; and Bruce then says that he knows his children did not care for him, and that he wanted to be as close to them as their mother but did not know how. He says he thought life would be tougher on Cliff than on Ned or Kate and was tough on Cliff to prepare him—which nearly makes Ned snort (Ned understands; and he sees the sympathy and the wrongness of his father’s attitude). When Sally returns, she asks Ned if he received what he wanted and he says, “Yeah. I got some books.” She then asks him not to tell Bruce about what happened between Ned and Kate—and Ned is humbled and shamed to realize that Sally knew. He cries; and she says she forgave him a long time ago, before suggesting another aspect of the family trouble he had not imagined. In Ned’s last conversation with their father Bruce, Ned offers the father balm instead of complaint or conflict, allowing Bruce to die with more peace; and Ned later says that it is his sister, Sally, who was their father’s greatest achievement—and Ned burns the pages of notes he has written, pages that document the story we have just seen. Ned has learned something he has not known before, but will he heal? Or will he still desire the thing that poisoned his soul? Just because what you want does not exist, does not mean that you will cease to want it, even if it means your destruction.

Essay submitted 3/11/11