The 33rd Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF) Report

The 33rd Hong Kong International Film Festival (HKIFF) was spread out over three weeks, from March 22 to April 13, 2009. Even though it no longer seems to have the cache it once had (and which is now held by the Pusan film festival in The Republic of Korea), as a scholar of Asian (especially East Asian) film, the HKIFF is still a very important annual event for me, perhaps the most important. Unfortunately, I can never commit such a long time period at the end of the school year, although this year, I was able to attend from March 27th to April 5th. According to my calculations, 90 new Asian feature-length films and an almost equal number from the rest of the world (mostly Europe, especially from France) were shown in more than 10 different venues over the duration of the HKIFF this year. But, significantly HKIFF also does retrospectives, and this year, they mounted major tributes to Tsui Hark’s Film Workshop, accompanied by a bilingual (Chinese and English) book, and, in association with the Hong Kong Film Archive, “In the Name of Love: the Films of Evan Yang,” one of the top HK directors of the 1950s and 1960s. There were smaller retrospectives devoted to the recently deceased Ichikawa Jun from Tokyo, and to “The Realist Dao” of Korean 1960s director, Yu Hyun-mok.

I wasn’t able to see as many new films from Hong Kong this year as I usually do as seven of the ten films in the Hong Kong Panorama 2008–2009 had screened before I arrived. But, I had seen one of them, The Beast Stalker (Jing Yan, 2008) on the plane from Toronto. Thanks to the great airline, Cathay Pacific, it was a thrill to finally see a good digital image in-flight, but I wasn’t as impressed by Dante Lam’s action thriller as the people who voted at The Hong Kong Film Awards to give the film Best Actor (Nick Cheung) and Best Supporting Actor (Liu Kai-chi), a week after the film festival’s closure on April 19. Cheung certainly made a strong (and somewhat sympathetic) villain, and the car crash, which is the centerpiece of the film, was brilliantly mounted. I had already seen Sparrow (Man Jeuk, 2008) at last year’s FanTasia festival in Montreal, and it provides more evidence (if any were needed) that Johnnie To and his Milky Way Image company continue to be the most innovative and successful Hong Kong filmmakers, by far. The only other film in the Panorama that I saw was Tammy Cheung’s documentary on the 2004 HK Legislative Council elections, entitled, Election (Suen Kui, 2008). Without recognizing many of the candidates who were filmed in action, mostly promoting themselves, I was surprised at how enlightening and amusing Ms Cheung’s coverage was. She has rapidly become the most notable Hong Kong-based documentary, digital-filmmaker, and this most recent example of her observational approach—she refuses to employ voice-over narration, or, even interviews—is a triumph. The audience loved it, although without some written on-screen text to identify the characters and the events, it may not be so successful internationally. Although she claims that she is absolutely not a “political” filmmaker, Tammy Cheung is nothing if not “courageous,” as she currently distributes the work of very independent and controversial Chinese mainland digital documentarians with her own company, Visible Record Ltd.

Six of the 16 feature film World Premieres at this year’s HKIFF were made in Hong Kong, and I was able to see three of them: Storm Under the Sun (Hongri Fenbao), a digital documentary on the Hu Feng “Incident” in the “Reality Bites” section, Glamorous Youth (Ming Mei Shi Kwong), a first feature in the Asian Digital competition, and Ann Hui’s latest Night and Fog (Tin Shui Wai DikYe Yu Mo), which had initially been shown as an Opening Night Gala. Hu Feng was an influential communist Chinese writer, who experienced a massive state-run “anti-rightist “campaign against him and his group of writers in 1955. Peng Xiaolian, one of the most successful graduates of the Beijing Film Academy, whose father had been whipped to death by red guards after being accused of being a member of the “Hu Feng Counter-revolutionary Clique,” and S. Louisa Wei, a film professor at City University of Hong Kong co-directed Storm Under the Sun in order to set the record straight and to trace the personal histories of those who were unjustly persecuted. Apart from some interesting use of animation that lightens the tone of the work (perhaps, unadvisedly), Storm Under the Sun is far too formally conventional, and heavy on the spoken word and written text. Although it is extremely well intentioned, and, an arguably important documentary, the film also feels overlong at 135 minutes. Prominent Hong Kong film critic Philip Yung should be praised for the consistently fine acting and some raw scenes of parent/teenage conflict in his debut feature, Glamorous Youth. But, the drama is not sustained over its 140 minute running length, while the digital color balance is extremely erratic, and, the film is not especially well shot and edited. One of the surprises of this year’s HKIFF was provided by Night and Fog. Coming after Ann Hui’s universally admired The Way We Are (2008), which won her the Best Director and three other Hong Kong Film Awards on April 19, her new film, on the subject of extreme wife abuse, was not so well received on its premiere. One must applaud Simon Yam for taking on the horrible role of the brutal husband, and it would have been a shock for audiences to see the other side of residential life in the community of Tin Shui Wai, which had been lovingly portrayed in The Way We Are. In the festival catalogue, the director gives three reasons why she “had” to make this film: “a) because the subject fascinates me, and this fascination has grown during the five years since I started the research, b) the story and its characters afford a chance to show the kind of life which a lot of people are living in Hong Kong now, and c) it is also my studied intention to shoot as many contemporary, realistic subjects as possible because I am beginning to see this as my most suitable, heartfelt role in filmmaking.” (p. 31)

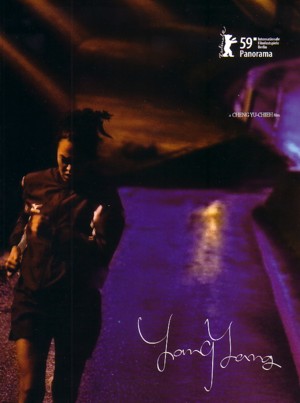

On the whole, I was more impressed this year with new films from Taiwan than those from Hong Kong. No puedo vivir sin ti (Bu Neng Mei You Ni, 2008), is the second feature film directed by actor Leon Dai, and was shown in a small “Young Taiwanese Cinema” section. Inspired by a real-life story of a father threatening to jump off a bridge with his daughter, Dai explores the possible background to it and decided to shoot his film digitally in black and white (transferring it later to 35mm) and in the Fukienese dialect, in order to impart a strong sense of realism. Dai successfully gives an atmospheric representation of dockside poverty, where the father struggles to support his daughter by occasional work, including diving. Yang Yang (2008), presented as a Gala screening with the director and principal cast members in attendance, is an even more impressive second feature, which like No puedo is considerably different from the usual long take “art film” style associated with Taiwanese cinema. Director Cheng Yu-Chieh’s not altogether positive title character is a young Eurasian athlete (Sandrine Pina) who decides to have a “no-strings attached,” one-night-stand with her “sister’s” boyfriend, who refuses to leave her alone. The camera follows Yang Yang around constantly, but she says very little, so that we cannot fully understand her motivations. But, ultimately she emerges as quite a sympathetic figure, battling for her rights as a young woman of mixed race and to be a success in the world of entertainment. In the latter endeavour, a talent agent with whom she falls in love helps her. But, her desire remains unrequited…

Malaysian film production has been notable in recent years, although, as far as I know, films directed by only two Malaysians have ever been shown in Montreal. Ironically, both, James Lee and Yasmin Ahmad were the two Malaysian directors represented at this year’s HKIFF. Known for his deadpan humour, “slacker” characters, and long take style (Room to Let, 2002, The Beautiful Washing Machine, 2004), Lee’s latest work in this mode, Call If You Need Me is less comic, but no less emotionally distanced than his previous work. Interestingly, Call If You Need Me is focused on small-time gangsters, and could even be regarded as a kind of anti-genre film, as most of the key action occurs off-screen. The opening sequence is filmed with a static, flat camera observing a group eating, drinking, popping pills, and smoking, and, eventually, sleeping—drunk or drugged—hardly what one expects from a “gangster” movie. Typical, the punks treat their girlfriends badly, and sit in cars a lot, which makes sense because they collect bad debts and reclaim cars. James Lee has arguably made the first “slacker” gangster film, and it won him the second place (“Silver”) award in the Asian Digital Competition. Yasmin Ahmad’s Talentime (2008) was appropriately included in the “Globalvision: Multiculturalism in Action” section. Like her previous, highly acclaimed feature, Mukhsin (2006), ??Talentime??—the name of a high school musical contest—deals with the multi-racial problems in Malaysian society. Perhaps too much time is spent on the young performers’ auditions and the quirky family, which mixes (very) British, Malay and Chinese ethnicities. But, one cannot fault Ahmad’s intentions with this film. She is surely the most significant multi-cultural filmmaker in the region.

Surprisingly, only one film from Thailand was on view this year, but, Sawan Baan Na (Agrarian Utopia), directed by Uruphong Raksasad, was one of the most beautiful and unusual works in the 33rd HKIFF. Seemingly placing fictional characters in documentary situations, Agrarian Utopia compares and contrasts traditional and alternative (somewhat “hippie”) farming methods, and doesn’t shy away from the hardships incurred. Having been trained as a filmmaker and photographer, and having worked as an editor and post-production supervisor in the commercial Thai film industry, Raksasad brings a strong cinematic and photographic sensibility to his work. Idyllic landscape shots, with striking skies, often filled with rain clouds are interspersed with closely framed, visceral hand-held moving camera shots and rapid editing. Especially impressive are scenes where children run in rice fields, splashing up mud, much of which smears the digital camera’s lens. Initially, we always see a Buddhist temple in the background of repeated, extreme long shot framings of the landscape. But, near the end of the film, a group visits the temple, and the camera follows them inside. A long shot then zooms out to show habitation in the foreground. Gradually, civilization encroaches on the rural setting, and, perhaps, by association, pollutes the environment.

There were an equal number of new Japanese films this year as mainland Chinese films (16), some of which are well-worth mentioning. Another good entry in the Asian Digital Competition was Mubobi (Naked of Defences, 2008). Director Ichii Masahide’s subjects are very ordinary women who work in a factory, and who struggle with the men in their lives and who sacrifice for their children. In short, Mubobi, which had won the New Currents Award at last year’s PIFF, is a “realist” film, and, strikingly, all of the women are completely deglamorized, especially through the ridiculous-looking, clean body suits they must wear in the workplace. The last thing we can possibly do as an audience of this film is to see any of the women as objects of sexual desire. Sion Sono’s Ai No Mukidashi (Love Exposure, 2008), on the other hand, is anything but “realist” and is concerned with young Japanese male obsession with girl’s panties, and “peek-a-panty” clandestine photography. It also contains a hilarious critique of Catholicism, and many antics of martial arts heroines. Although I was only able to view about half of Love Exposure??’s four hours running time, I am looking forward to seeing it in its entirety on another occasion, perhaps this summer’s FanTasia festival, where it is sure to be one of the biggest hits. It is hilarious! I reserve my highest praise of Japanese films this year for Kore-eda Hirokazu’s ??Aruitemo aruitemo (Still Walking, 2008). I confess to not always admiring Kore-eda’s work, but, in an era where so many recent western films are focused on big middle-class family gatherings (e.g., Arnuad Desplechin’s Un conte de noel and Jonathan Demme’s Rachel Getting Married, both 2008), it is rewarding to find such a subdued approach to a family get together, reminiscent in its subtleties of the late Ozu Yasujiro’s films, although marked by a far more realist style of acting and staging.

One of the aspects of this year’s HKIFF that clearly marks a shift is the exhibition of films in digital formats. Of course, many more films are now being shot digitally, and, in the past many digitally shot films were transferred in order to be shown on 35mm copies. But this year I count no fewer than 36 of the 76 new East and South East Asian films were projected digitally, over 47%. By contrast, only 8 of the 65 new European feature films were projected digitally, just 12% of the total. Perhaps, we are experiencing a much faster move to digital projection in Asia than other regions. The problem with this year’s festival is that there was a range of technologies available from one theatre to another. Surprisingly, perhaps, the Science Museum theatre didn’t boast a top-of-the-line projector. This is where I saw DVCAM copies of Love Exposure, and Mubobi, as well as Terence Davies’ documentary, Of Time and the City (UK, 2008) and Raul Ruiz’s Balzac inspired vampire tale, Nucingen Haus (France, 2008), both on DigiBeta, and all of the screenings were hampered by a lack of resolution and for the DigiBetas, too dark an image. The smaller Space Museum theatre fared better, but at this venue, there were vast differences in resolution between the best looking film I saw there, Agrarian Utopia (which, according to the catalogue was shown on DigiBeta) and the poor Beta SP copy of Call If You Need Me. [1] A major breakthrough occurred this year with the installation of Barco (Texas Instruments, DLP) Digital Cinema projectors in two cinemas at the UA City Plaza and the UA Langham Place. All of the HDCAM copies were shown in each of these theatres, and the projection was of such high quality that one could notice real differences of quality between different copies. I have already discussed problems with Glamorous Youth (above), but the most striking contrast came with viewing a double bill of Ichikawa Jun’s last work, Sutsu wok au (Buy a Suit, Japan, 2008, 47 min.), and Jia Zhangke’s Heshang de Aiqing (Cry Me a River, China, 19 min.). Buy a Suit, which follows a young woman looking for her homeless brother, contains some good Tokyo street scenes, but has an ugly aesthetic, so obviously digital, with very sharp, contrasty, overly bright (or dark) images. It was probably transferred from a lower grade source to HDCAM, which only serves to highlight its flaws. On the other hand, Cry Me a River looked beautiful. In Suzhou, (often called the “Venice” of China), four classmates have a reunion with their former professor. They used to be two couples, and when they ride on a gondola on a canal, and when one of the couples visits a park, one can surmise that Jia had deliberately chosen highly romantic settings for un-romantic re-unions. Nostalgia, in turn is tinged with sadness through the effect of rain on the canal. The muted colour scheme, brilliantly rendered in HD is broken only once, when, near the beginning, the camera pans left from dinner with the professor to a traditional Beijing Opera performance (of the Butterly Lovers?), in vivid, rich hues, including red and gold.

One other digital film that I saw really benefited from the “Barco Experience,” the finest new film I have seen so far this year, Abbas Kiarostami’s Shirin (2008). To some extent, we are witnessing a revival in the quality of Iranian film this year, with six films on view at the HKIFF including the Berlin prize winning, Darbareye Elly (About Elly). Director Asghar Farhadi presents an unusually frank exposition of young people “camping out” at a house on the Caspian Sea, complete with scenes of them playing charades and music. Sensationally, the group tries to match the title character Elly with an unattached young man. But, the film eventually becomes more conventional, when the “engaged” Elly is seemingly punished for her transgression. Shirin is much more radical as a “film.” Kiarostami presents the traditional epic love story of Kosrow and Shirin, but only on the soundtrack. Amazingly, the image track only shows film audience members apparently reacting to the film, which we can only hear. Clearly, Kiarostami was interested in audience reactions, and, as he has said in interviews, he asked his subjects, predominantly women, to react in certain ways as if they were reacting emotionally to events in a film. What I did not expect was to experience the poetic nature of “Kosrow and Shirin” through the voices (and sub-titled translations), sounds and music of the off-screen story. Even more remarkably, I gradually understood that, with its graphic violence (of war) and passionate love between a man and a woman, there wasn’t any way that Kiarostami could have made a film in today’s Iran of this story, because of all of the censorship restrictions. Brilliantly, then, through his use of sound, and through the beauty and expressive facial reactions of Iranian women (and Juliet Binoche), rendered through compositional balance and subtle lighting changes (justified, perhaps by the flickering of the non-existent images), and combined through editing, Kiarostami presents us with a unique film.

This year, I didn’t spend as much time as I usually do at the Hong Kong Film Archive (HKFA). I had seen a number of Evan Yang titles in the past through various retrospectives, especially the one devoted to the Cathay company, where he was a house director. In the past the HKIFF had set a trend for digital projection, in an attempt to preserve individual film prints in their collection. It was also the first place where I had ever seen digital sub-titles projected at the bottom of the screen. Both screenings I attended this year were digital copies of The Beauty and the Dumb (1954, directed by Tang Huang and written by Yang), and Madame Butterfly (1956, shown without sub-titles). Yang’s script for the older film, based on Anatole France’s The Man Who Married a Dumb Wife is full of comic satire, centered around a clerk who is trying to get his mute daughter (played by Li Lihua) married off to the boss’ son. Surprisingly, the black and white film contains many exterior shots of Hong Kong, showing how the natural landscape has become so overtaken by the city over the last 40 years. Madame Butterfly is a very odd example of a film attempting to forge good relations between Hong Kong and Japan. Actually made in Japan, but with a Chinese-speaking cast, including Li Lihua as the Japanese bride of a Chinese visitor, this version of Madame Butterfly corrects the original, by deliberately not having the man abandon the woman. It features a colour sequence of Li Lihua performing on stage with the all-female Takarazuka Revue.

There were three screenings of “Archival Treasures” at the Science Museum, two of which I attended (in part), and I was impressed first of all that film prints were shown (rather than digital copies), and secondly that the screenings were very well attended. But the retrospective highlight, by far was the much-anticipated screening of a film that had been believed to be lost, Fei Mu’s Confucius, made in Shanghai during the “Orphan Island” period in 1940, when Japanese forces occupied most of the city. A nitrate print was anonymously donated to the HKFA in 2001, and after years of research and restoration, in conjunction with L’Immagine Ritrovata in Bologna, Italy, a premiere was scheduled at the Hong Kong Cultural Centre during the HKIFF. I have written elsewhere, speculating that Fei Mu was probably the very first Chinese filmmaker who consciously referred to traditional Chinese landscape painting, and on the evidence of Confucius, we can surmise that, with this film he attempted to invoke the look, and implicit movement of narrative scroll painting as well as other Chinese traditions. [2] The film is so highly stylized, in its costuming, gestural acting and delivery of dialogue, that one might accuse it of being too “theatrical.” However, there are many instances of intricate staging in depth, and of panning camera movements, as well as some instances of tracking in depth to indicate that Fei Mu was thinking beyond the proscenium arch frame. On the first two occasions that Confucius is appointed to a ministry job, the camera tracks in with him to his appointment, with his elaborate hat in the lower foreground. The panning camera often follows a character’s gaze or movement and characters often move laterally across the frame. Although the camera never laterally tracks anyone, these other instances of movement could be intentional reflections of scrolling a painting. The camera is also often angled upwards to view the sky or in a slight high angle position looking downwards. Both strategies suggest that Fei Mu was consciously thinking of traditional Chinese art. Most strikingly, in at least two shots where the camera is at right angles to the background wall of the set, we notice a rectangular cut out in the wall through which we seem to be viewing the natural world, or a painting of trees and flowers. Our perception of depth and of reality seems to be questioned here, and, elsewhere whenever flowers, bushes or other natural features are included in the sets of Confucius, they look artificial. Hopefully there will be other opportunities to see Fei Mu’s highly experimental, albeit declamatory and ponderous film on one of the most important figures in Chinese history, in order to make a more accurate assessment of its status, but, from my perspective, it looks already to be one of the most significant of all Chinese films, if not one of the “greatest.”

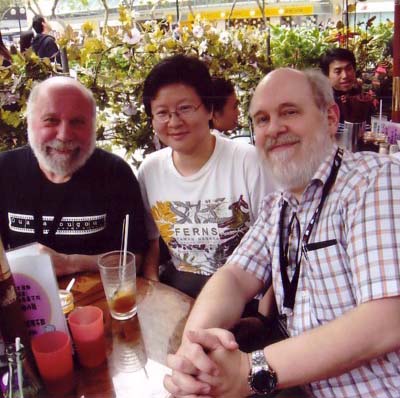

It is always a pleasure attending the Hong Kong International Film Festival, and, this year was no exception. The organizers are constantly struggling to stay afloat financially, and the duration has stretched back into March in order to connect up with the burgeoning Asian Film Awards and the HK Film Market, making it more difficult to attend everything. I’m always happy to meet old friends, especially those who share a love of Hong Kong cinema. So, it was especially pleasing this year to watch the first Tsui Hark directed Wong Fei Hong film, Once Upon a Time in China (1991), after an absence of a few years. How remarkable Jet Lee’s acrobatic performance still looks at a distance, and what a wonderful action director Tsui Hark was, in those days. Sitting down briefly after the screening with fellow fans, David Bordwell, King-Wei Chu and Yvonne Teh to reminisce about the good old days of Hong Kong cinema was quite sad, really. Not as many foreigners travel to the HKIFF any more, and the main reason must surely be that Hong Kong cinema has fallen on hard times. There is far more respect, internationally, for Hong Kong film than, possibly, there has ever been, and many more co-productions with the mainland now take place. There are good opportunities, still, for independent filmmaking in the SAR, and there seem to be more and more film courses on offer at the local universities. I am optimistic that this great film territory will prosper in the future, and I have every intention of attending the 34th HKIFF in 2010.

Endnotes

1 All credit to the Hong Kong International Film Festival Society for the consistent attention they pay to their publications, which, in the case of the excellent catalogue, involves listing the format in which every film will be shown. If only Canadian film festivals exercised the same attention to detail.

2 “The Presence (and Absence) of Landscape in Silent Chinese Films,” paper read at The Centennial Celebration of Chinese Cinema and the 2005 Annual Conference of ACSS; “National, Transnational, International: Chinese Cinema and Asian Cinema in the Context of Globalization,” June 7, 2005, Beijing. The conference continued in Shanghai, June 9 and 10, and the paper was published in volume 2 of the conference proceedings.