Being There: The 2010 Sundance Film Festival

Much of the talk about the 2010 Sundance Film Festival was about expansion: into far-flung venues as well as into the virtual world. This year for the first time the fest sponsored contemporaneous screenings of selected festival films all over the country including New York, Los Angeles, Chicago; San Francisco; Nashville; Ann Arbor, MI; Brookline, Massachusetts; and Madison, Wisconsin. More films were made available on-demand to American television viewers, while others were streamed globally via YouTube. Sundance is not alone in this; the South by Southwest and TriBeCa festivals are mounting similar initiatives. This development is in tune with what Manuel Castells has called modernity’s “networked, ahistorical space of flows,” which today has overridden the “scattered, segmented places, increasingly unrelated to each other” which characterize traditional societies. Yet Castells also points out that even in this brave new world of intangible connections, people actually live in places, not spaces. “A place is a locale whose form, function and meaning are self-contained within the boundaries of physical reality,” Castell observes. “Physical” is the key word here. We have bodies, and they anchor us to particular places. No matter how many texts messages we may send or video games we may play, it’s ultimately the places we inhabit that matter most deeply to us.

The art form that more than any other has ushered in today’s world of virtual reality is film. Paradoxically, however, movies also possess an unrivalled capacity to conjure up potent portraits of distinctive surroundings, introducing us to far-flung locales and reminding us of the comforting aura we attach to familiar milieus. The Sundance Fest has always specialized in such films, regularly giving its audience glimpses of out-of-the-way locales and subcultures. Some of the most memorable productions I have seen there foreground the role played by specific places in the lives of the people who dwell in them. A few of these films, like Frozen River and In Bruges, announce a concern with settings in their very titles; others simply introduce audiences to locations many of us have never before imagined. Captain Abu Raed (Amin Matalqa, 2007) highlights the beauty of Amman, Jordan; while Push (later retitled Precious) (Lee Daniels, 2008), reveals the squalor of the Harlem slums. Such places can be anywhere in the world. Sundance has never viewed international cinema as its main charge, but recent years have seen an increase in the number of foreign films on the program, showcasing unexpected locations not only in America but also from beyond our borders. This year, with John Cooper newly at the helm, the festival has pulled back slightly on its commitment to movies from abroad: only twenty-eight such titles were screened rather than the thirty-two I counted on last year’s slate. But the project of examining the emotional tonalities evoked by unique places was still a major component of this year’s films. Some drew out themes raised by spectacles of vast natural terrains while others offered visions of the Byzantine human constructions called cities.

Winter’s Bone (Debra Granik, 2009), the production that took top prizes in both the Dramatic and Screenwriting Competitions at this year’s festival, evoked a sense of place most forcefully of all the movies I saw there. Set in the remote reaches of the Missouri Ozarks where grinding poverty is a way of life, Winter’s Bone chronicles the struggles of Ree Dolly, a young girl who must find her missing father in order to keep the family homestead. Bertold Brecht once claimed that all snapshots of economic destitution are necessarily glamorized by the very nature of photography; but Granik, supported by her capable cinematographer Michael McDonough, does all she can to cut through to the fundamental wretchedness of such an existence. In Winter’s Bone the weather is frigid and the trees forlorn. Yards are adorned with decaying putti and chipped plaster-of-Paris butterflies. Faded shards of clothing hang stiffly in ragged rows at the back of dilapidated wooden shacks while garlands of stones festoon ramshackle porches. Scrawny horses and mangy stray dogs barely subsist in this godforsaken land, and the human inhabitants are hardly better off. A network of interrelated families eke out a hard-scrabble existence by illegally concocting crystal-meth (or crank, as they call it). This secretive covey all share the mean, pinched look and explosive temperament of hardened addicts.

Winter’s Bone

As Ree, Jennifer Lawrence spends much of the time trudging over arduous mountain terrain and enduring brutal abuse from her relatives as she searches for information about her parole-jumping father. She must find him to save the cabin that serves as a safe haven for her disabled mother and two young siblings. The lengths to which Ree is prepared to go to keep her hold on an existence that is precarious at best testifies to her deep attachment to the place where she has her roots. She even explores the possibility of consigning herself to a stint in the army if it will provide her with the wherewithal to hang on to her refuge. When an opportunity arises to sell the forest surrounding the family’s home, she has ominous dreams (rendered in stark black and white) in which the woods seem almost to come alive. The brother and sister for whom Ree has taken responsibility are like small woodland creatures; when she gives them a lesson in how to shoot squirrels, she might be a barn cat teaching her kittens to hunt.

Through all of Ree’s travails Lawrence maintains an unrelenting demeanor of dogged stoicism. Though appropriate for the role, her performance does not call for the displays of passion or range of emotion that makes for typical Oscar bait, despite what some commentators have suggested. In place of showy theatrics, Lawrence quietly crafts a determined figure that merges with her barren surroundings in what is ultimately an allegory of nature stripped bare.

Another kind of barren world was on display in Restrepo (Sebastian Junger and Tim Hetherington, 2010), which won the documentary award at this year’s Sundance Festival. For courage alone filmmakers Hetherington and Junger deserved the prize. The Korengal Valley, where the film is set, is said to be the most dangerous area in Afghanistan, yet the filmmakers made ten trips there beginning in 2007 to record the activities of the US army brigade charged with securing the area. Restrepo, the mountain outpost the soldiers build during this time, is named after the platoon’s first casualty and signals the importance of the homosocial bonds the men must cling to in the midst of an environment in which every rock could conceal a Taliban sniper. Guitar-strumming and loud rock-and-roll offer these young Americans stranded far from home brief respites from the deafening explosions and gunfire to which they are frequently and unexpectedly exposed. Their perch near the top of the mountain allows for a commanding view of the valley below, yet the men remain alarmingly exposed. What Mary Louise Pratt once labeled the imperial gaze, a view that looks condescendingly down on a landscape from a vantage point on high, is denied these would-be conquerors. Instead, they survey a rugged terrain that remains inscrutable and ominous. Though the Valley’s Afghani natives suffer losses just as the foreigners do, they seem more protected as we see them sheltered in their tiny enclosures. Most of all, the village elders, with their leathery faces and cautious eyes, convey a hard-won familiarity with this forbidding countryside—in stark opposition to the naïveté of the American newcomers.

Restrepo

Such contrasts coupled with the fascination of the land itself go a long way toward compensating for ??Restrepo??’s lack of narrative build-up. No climactic event rounds out the action; in the end, the soldiers just leave this forbidding region. Interviews the men submitted to afterwards are scattered through Hethrington and Junger’s film, rounding out the characters of the young soldiers and making them figures of empathy. But Afghanistan itself, enigmatic and forbidding, remains the star of the film.

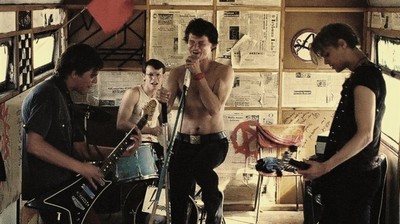

With an eye to avoiding controversy and attracting a broad audience, Hethrington and Junger have insisted that Restrepo is not political. A similar motive undoubtedly led Jacek Boruch, the young writer-director of All That I Love (Wszystko, co kocham, Jacek Boruch, 2009), to claim that his film was a-political. A charming, modestly conceived Polish entry in the Sundance lineup, All That I Love is set in 1981, just as Solidarity took hold in the country. The action occurs in Hel, an attractive town in the Baltic Sea at the tip of the breakwater that creates a safe harbor for Gdansk, whose shipyards formed the epicenter of the Solidarity movement.

All That I Love chronicles the social upheaval that defined this historical moment from a perspective that is clearly anti-Communist. But Boruch is much more interested in the personal than the political. An offhand allusion to Pope John Paul, who was such a decisive force in Solidarity’s ultimate triumph, is framed as a joke. And while the town is roiled by protest and martial law, it’s the romantic travails of the movie’s teenage hero Janek (Mateusz Kościukiewitz) which take center stage. If Janek’s punk rock band incites the incendiary passions at a high-school dance, the cause has more to do with the angry rhythms of the music than with any social agenda in the lyrics. The Czech-born playwright Tom Stoppard similarly used rock music as a major motif in Rock ‘n Roll, his chronicle of the Czech Spring that took place a decade earlier, but Stoppard is a more ambitious artist than Boruch. Though set in a seminal time and place, All That I Love backs away from confronting the full implications of its milieu, content to focus instead on a deft rendering of one young man’s coming-of-age story

All That I Love

A more cosmopolitan setting was on display in Twelve (Joel Schumacher, 2009), Sundance’s closing night offering, which takes place in Manhattan. The story sets over-privileged teenagers from the Upper East Side against ruthless Harlem drug dealers, concocting an unsavory melting pot that eventually boils over into a blood-soaked climax. Many commentators found the story’s trajectory, which begins as a slick satire of the idle rich and morphs into an action-melodrama, ill-conceived. But if Twelve works at all, it’s because it reveals Manhattan as an urban hothouse where such extremes can readily co-exist and, on occasion, clash. In one early scene a group of spoiled rich kids walks by a fast food chicken joint where Black patrons are eating: Though we may initially respond to this shot as a vision of polar opposites captured in a single image, we soon come to understand that these cultures are not diametrically opposed but rather joined at the hip.

The glue that cements them is drugs, and the movie’s central character (played by “Gossip Girl’s” Chase Crawford) is a dealer. Significantly, the dealer is called “White Mike,” a nickname that allows his rich clients to repress his connection to the Black underworld they are thoughtlessly supporting. If White Mike’s sometime girlfriend repeatedly brings up Albert Camus’ novel The Plague, it’s because the filmmakers (like Nick McDonnell, the seventeen-year-old who wrote the novel on which the story is based) believe that drugs are the epidemic that holds sway in today’s New York. Pretentious? Maybe; but true just the same.

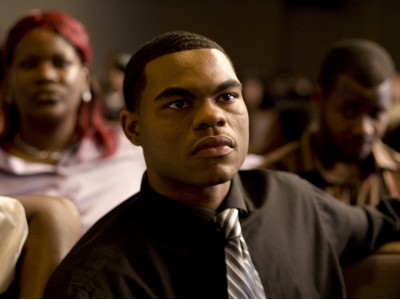

The Detroit of Bilal’s Stand (Sultan Sharrief, 2009) lacks both the elegant townhouses and dangerous street life that energize the hyped up Manhattan presented in Twelve. In their place Sharrief and his cadre of community-based helpers focus on a family-owned taxi stand in a shabby neighborhood in Detroit. The benign denizens of this marginal business may be scraping by economically, but they bring spunk and humor to every endeavor. If the film’s story about a young man struggling to escape from poverty is a familiar one, we can buy into it here in large part thanks to Julian Grant’s ingratiating turn as the title character. Bilal may be torn between his loyalty to his family and his desire to get ahead, but as soon as he has a chance to compare his decrepit surroundings in the inner city to the swank suburban campus of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, his mind is made up. “I had no idea there could be such a beautiful place so close to where I live,” he says.

As part of fest director John Cooper’s “Next” series, Bilal’s Stand was made on a shoestring and looks it. But what it lacks in budget, it makes up for in offbeat charm. The funky animations that Sharrief has drawn over some of the images get repetitious at times, but they mostly add to the humor. And Sharrief has drawn winning performances out of a mostly amateur cast and has successfully captured the rhythms of a neighborhood that rarely finds a place in today’s media landscape. From the evidence of this small gem of a film, Sharrief seems destined for bigger things. Hollywood agents, take note.

Bilal’s Stand

As sociologist Robert Park observed almost a century ago, identities in today’s cities are defined by occupation. Among the working class characters in Bilal’s Stand such job-based identities are universally shared. Women work along with men, and all participate equally in family life. By contrast, in the upscale Boston environment on display in The Company Men (John Wells, 2009), occupation defines identity only for males. The lone company woman (played by Maria Bello) has a life shown as woefully incomplete. She lacks family ties; her only intimate relationship is with a married man. Her male colleagues, by contrast, draw sustenance for their daily forays into the corporate bullpen from their place at the helm of domestic enterprises, taking pride in their ability to support their families without having to resort to sending their wives out to collect second paychecks. These families are housed in suburban mansions well away from the headquarters of GTX, the mammoth shipping firm at the center of the story. For these men to lose their jobs is to lose their masculinity, and they handle this psychic wound poorly. Similar scenarios drive recent films from Asia (Tokyo Sonata, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2008) and Europe (Time Out L’emploi du temps), Laurent Cantet, 2001), suggesting that men’s roles as breadwinners still form a cornerstone of their sense of themselves as male in most parts of the developed world.

A first foray into film directing by TV heavyweight John Wells (who also wrote the screenplay), The Company Men features a preoccupation with labor issues that is not surprising coming from a man who has intermittently headed up the Writers Guild of America since 1999 and has spearheaded the group’s battles with management over compensation issues. Though the three main characters in The Company Men are executives, the film has no sympathy for the corporate culture of GTX. The company’s CEO James Salinger (Craig T. Nelson) harbors grandiose ambitions which include a lavish new corporate headquarters to be adorned with multi-million dollar paintings. To achieve these goals he fecklessly amputates major corporate assets—some of which also happen to be human beings. The first to go is the firm’s young marketing chief Bobby Walker (Ben Affleck), next up-from-the-ranks veteran Phil Woodward (Chris Cooper), and finally the company’s second-in-command (and Salinger’s former college roommate) Gene McClary (Tommy Lee Jones).

In chronicling the travails of these three casualties of corporate downsizing Wells offers a few toned-down pitches for a Marxian vision of unalienated labor. Giving Bobby a tour of the abandoned company shipyard, Gene laments the loss of a business model based on “building something you could see.” Later, Bobby, who has been forced by necessity into accepting a construction job offered by his working class brother-in-law Jack Dolan (Kevin Costner), pleads with Jack to keep him on, resisting the prospect of returning to a corporate environment he now sees as abstract and soulless.

The Company of Men

Ultimately, Gene decides to put into practice his utopian vision of a business culture based on making tangible things. But the movie hedges about whether we should take this project as anything more than a nostalgic gesture towards the past made by an aging executive who is too used up to envision a better future. Yet Wells can’t offer an alternate vision. Instead he opts to end on a note of studied ambiguity that allows viewers to decide for themselves how realistic Gene’s project may be. As for me, I didn’t buy it: America, for better or for worse, will never again be a center of manufacturing in an increasingly globalized world of technological marvels, whatever we might wish.

Wells is not only a labor leader but also a television innovator. His most famous shows, “ER” and “The West Wing,” were notable for their “walk and talk” style of filming dialogue, which responded to the new opportunities made possible by the increasing size of television sets. Wells’s programs eased up on the relentless close-ups that had dominated TV visuals up to then, combining these with kinetic interludes that mingled talk with action and demanded greater audience involvement. With the able support of cinematographer Roger Deakins, Wells largely abandons the walk-and-talk style in The Company Men, focusing instead on a classical cinematic look in which the camera doesn’t move incessantly, settling in for close views of interactions among the story’s many characters and balancing these with expansive long shots of leafy suburban streets, sterile corporate offices, and the skeletal remnants of abandoned factories. In one especially telling image the camera watches from above as Gene McClary enters the palatial dwelling he shares with his cold, haughty wife just after he has been fired. We see Gene, a tiny figure below us, walk into the empty entry hall, pause, look around, and walk right out again. No words are needed to describe his decision or why he made it. Here is a moment that could only be savored on the big screen.

Until televisions become gigantic and houses massive enough to accommodate them, cinema’s oversized images will remain the preferred mode for transporting images of distinctive places to every part of the globe. But why travel far to see them? Given the movies’ ability to make the local global, do you really have to bother schlepping your pre-modern body to a film festival? Why not just see movies at your neighborhood arthouse? The answer to this question lies not in the physical space in which a festival like Sundance occurs but in the communal space it cultivates. Even if you don’t go to the parties, don’t gossip with others in the lines outside of the theaters, and don’t engage in celebrity sightings, a festival like Sundance fosters an auspicious mood of anticipation and receptivity that is part and parcel of what is now called cinephilia. Directors and other production personnel appear after many screenings to answer often-acute questions from the audience. And there exists at all these events an atmosphere of expectation and respect for what filmmakers have attempted—even if it is not always achieved. A good film festival puts you in a good mood to see movies. And that is a gift to be valued no matter where you are.