17th Bradford International Film Festival, 16-28 March 2011

Woody Allen’s You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (US/Spain, 2010) was the opening film of this year’s festival. Allen is old enough to take an Olympian view of human foibles and there are echoes of A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy in his playful treatment of the characters. Like the underrated Match Point this is one of his London films, which means that it is about people who work in art galleries, go to the opera and have private means. Has Allen never seen a Mike Leigh film? When Alfie (Anthony Hopkins) runs off with a prostitute, his wife Helena (Gemma Jones) turns to a fortune-teller (in New York she would visit her psychiatrist). Her daughter Sally (Naomi Watts) is married to Roy (Josh Brolin), a writer whose novel is never quite finished. Sally is tempted into a relationship with her boss, while Roy becomes besotted with a girl who lives in the flat opposite and whom he watches through the window. She plays the guitar in what appears to be a sitting room. This strikes a false note given that anyone with a passing knowledge of British outside plumbing would identify the room as a bathroom. The detail points up my difficulty with the film: though foreign directors can provide a fresh perspective on a society, Allen seems stalled in a transatlantic world, never getting to grips with Britishness. Every scene is bathed in Californian sun – even in the rain – while Watts fails to emulate her British colleagues in anglicising Allen’s dialogue, which is a weakness given that she is a central character. The older generation lead the way in ensemble acting, so that Alfie, Helena and their friends are more convincing and more interesting. Allen’s work is always worth watching, but on the evidence of this film, travelling has failed to jolt him from his comfort zone.

An old performer befriends a young dancer in an Americanised version of London and regales her with epigrams. They fall in love. Not Woody Allen this time, but Charles Chaplin in Limelight (US, 1952). This launched a retrospective of Claire Bloom’s work which preceded an interview with the actress. Limelight was old fashioned on its first release and compares unfavourably with The Red Shoes (1948), with which it has thematic similarities. Chaplin is at his best performing in the music hall acts at the end of the film. Elsewhere as writer/director he wallows in pathos, but you still brush away a tear at the end. Islands in the Stream (Franklin J. Schaffner, US, 1977) is a rarity which Bloom asked to be screened at the festival. Adapted from Hemingway’s final and unfinished work, the film begins like Jaws and develops into The African Queen, the latter section being the more successful. The print has that rosy glow of a fading colour film, which should remind us of the fragility of our cinematic heritage. When money is short, saving films might be a low priority, but wait until the good times return and the films may be beyond economic restoration.

Although not a documentary festival, Bradford always has a strong documentary strand. This year’s offerings ran the gamut of how factual events should be presented, the most successful examples being documentaries which present material in a straightforward fashion. Two in the Wave (Emmanuel Laurent, France, 2010) charts the emergence of the French New Wave and the subsequent split between Godard and Truffaut. With hindsight their differing personalities and ideologies made a falling out inevitable. There is always a tension between money and principles and given the budgets involved, film-making can become a battleground for the competing elements. Godard kept to his left-wing ideals; Truffaut was more willing to flirt with Hollywood in the quest for a wider audience. There is plenty of footage to draw on and Laurent uses it intelligently, with enough commentary to put the visual material in context. A model documentary. Deforce (Daniel Falconer, US, 2010) charts the decline of Detroit from a rich and integrated city to one which is poor and divided. The paradox is that a black population was attracted there by the high standard of living, but this increased tensions as the city’s fortunes declined. Employing interviews and statistics, Falconer looks at the drug culture, political corruption and institutionalised racism within the police. Economic factors are central to the decline, but these are less cinematic and are covered in less detail. Falconer offers no solutions, but neither can politicians. Outside the Law: Stories from Guantanamo (Polly Nash and Andy Worthington, GB, 2009) is more polemical in revealing how Guantanamo came into being and the issues which it raises. The film relies on interviews with British detainees and such legal luminaries as Clive Stafford Smith and Tom Wilner. There are questions to be answered, but the only interviewee from the official side appearing in the film is a Guantanamo chaplain. Given that President Obama has had to go back on his pledge to close Guantanamo, notwithstanding his credentials as a Democrat and a lawyer, the situation is more complex than a legalistic approach allows. This is a powerful but one-sided documentary. Greenwashers (Bret Malley, US, 2010) is equally polemical in exposing how companies can massage their green image for marketing purposes. This is documentary-making of the Michael Moore school. The sections of straight exposition work better than those showing the activities of the gimmicky Greenwashers, pretend public relations consultancy devoted to helping companies give their activities a cloak of environmental concern. How many of the encounters are staged is not made clear and the joke soon wears thin. Congo in Four Acts (Congo/South Africa, 2010) is one of several recent films from the Democratic Republic of Congo and is a compilation from three directors. In the two segments which work most successfully, we follow officials going about their work. Divita Wa Lusala and Dieudo Hamadi’s Ladies in Waiting shows the dilemma facing maternity ward patients. They are not allowed to leave hospital until they pay, but as they cannot afford to pay they remain there, blocking the ward to new patients. Hamadi’s second segment “Zero Tolerance” reveals the arbitrary legal process accorded to rape cases. Kiripi Katembo Siku’s two segments show indignation, but less sense of direction. Dance to the Spirits (Ricardo Iscar, Cameroon/Spain, 2010) follows the work of a traditional healer in the jungle of Cameroon. For anthropologists this is of interest, but for other audiences it lacks context. We need things put in Western terms. What are the diseases being treated? Do the treatments work? The claim is made that Western medicine does not recognise some of the diseases, but could this be because the healer gains his power by ‘treating’ non-existent diseases – a sleight of hand not confined to the jungle? A more critical approach is needed which examines the pervasive belief in witchcraft as central to ill health. A similar need for more analysis occurs in Hollywood on the Tiber (Marco Spagnoli, Italy, 2010), which charts the rise and fall of the Cinecittà studios as a centre for international productions in the 1950s. The film offers endless clips of stars and starlets, usually getting out of cars. You try to recall their names, but before you can place them, the parade moves on. Eventually Hollywood grew bored with Italy and moved on. Why it came, why it left and how the influx of talent and money affected the local economy and Italian film-making are not pursued. A wasted opportunity.

I missed the Aesthetica Short Film Competition and the Shine Short Film Award, but most programmes included a short with the main feature. There were fewer gritty urban crime dramas on offer this year, with comedy coming to the fore. I enjoyed The Filmmaker (Marcello Fabrizi, Australia, 2010), which introduces us to Mark, whose love life interweaves with his film-making which spans every genre. You applaud his optimism. In Bad Night for the Blues (Chris Shepherd, GB, 2010), a nephew takes his irascible aunt to a party at the local Conservative club. Alcohol and jealousy get the better of her pretensions of grandeur. The result is deliciously grim. Among more serious works I was taken by Satoru Sugita’s Kiyumi’s Poetry and Sayuru’s Embroidery (Japan, 2006). The friendship between two schoolgirls founders when Sayuru’s bicycle seat is stolen. There is an artist’s concern with colour. Debussy music is an appropriate accompaniment —the piece has the elusive quality of Debussy’s Jeux. Sugita has created a mood piece with an erotic undertow which needs to be seen more than once.

As befits a festival in Bradford, a new strand showcased films made in the North of England. What distinguished the five films on display was that they were made with no official support and on budgets ranging from £1,000 to £50,000. All were worth watching and at least three have soundtracks which could have a separate life on CD. Home-grown film-making of this quality deserves encouragement, so I hope the strand will become a regular feature of the festival. The problem is not so much making a film on a shoestring budget, but reaching an audience – a point touched on later. British indies are apt to be horror films, zombie films, gritty urban crime dramas or comedy crime capers. Two of the five manage to subvert their genres. Another sets itself against these well-trodden paths. This is the stylish Innocent Crimes (Jonathan Green, GB, 2010). Made with a budget of £10,000, this moody noir is the result of a collaboration between the director and George Telfer, one of the lead actors. The inspiration for his character was Harry Lime in The Third Man, though I was reminded of the suave villain in the lesser known Holiday Camp (1947) and the power play of Joe Losey’s The Servant (1963). A put-upon accounts clerk Farley (Michael Longhi) comes under the influence of the charismatic Charles Wells (Telfer). Fuelled by alcohol and jazz, the couple embark on a crime spree, but things turn darker when a girl intrudes into their relationship. The weak point is Farley’s mother, who seems too naïve for a domestic abuse officer.

Thomas Arslan visited the festival to introduce a short retrospective of his works. Three years ago the festival screened a retrospective of Christian Petzold’s films. Arslan is a fellow member of the Berlin School, but I found his work less accessible. There is a chilliness which distances me from his characters. This is apparent in A Fine Day (Germany, 2001), where a young actress (Serpil Turhan) leaves her boyfriend and encounters another young man on a train. She seems so devoid of emotion that any relationship comes as a surprise. Arslan’s latest feature In the Shadows (Germany, 2010) marks a change of direction from his earlier, less plot-driven pieces. Newly-released prisoner Trojan (Mišel Maticevic) looks to his former criminal boss to help him, though his wariness proves well founded when the boss tries to have him beaten up. A corrupt policeman is also keen to use him, but Trojan prefers to go his own way, staging a heist on a security van. This is a downbeat and efficient thriller, but is it anything more? It could be seen as a homage to Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samourai, or – in an echo of the Godard-Truffaut split – a play for greater box-office success. Take your pick.

New features make up the core of the festival and thrillers like In the Shadows seemed popular this year. Point Blank (Fred Cavayé, 2010) is the French entry. The wife of student nurse Samuel (Gilles Lellouche) is kidnapped to force him to deliver the injured criminal Sartet (Roschdy Zem) to rival gang members. When the plan goes awry, Samuel is on the run from both the gang and a corrupt policeman. He finds an unlikely ally in the injured but violent Sartet. Chases through Paris have become routine, from Frantic in 1988 to Tell No One in 2006. The frenetic pace distinguishes Point Blank, but for me the noise and urgency signify little. The characters remain ciphers. The Christening (Marcin Wrona, 2010) is one of a clutch of Polish films at the festival and was based on a true story. As we know from The Godfather, christenings can be dangerous occasions. Michal (Wojciech Zielinski) runs his own business and invites newly demobbed soldier Janek (Tomasz Schuchardt) to be godfather to his child. Michael is in debt to a criminal gang who allow no defaults. He wants to get the christening over before facing his problems, but the gang boss has other ideas. This is a well-paced and brutal film. According to the director who attended the screening, he had in mind the story of Cain and Abel. The problem is that adopting Janek’s point of view leads us in a different direction from the demands of the plot, so that he becomes an inconsistent character. This makes the final scene unsatisfying as well as unexpected.

Less formulaic films were more rewarding. One of only two features from the Far East, Seesaw (Keihiro Kanyama, Japan, 2010) developed from screenwriting workshops. Kanyama plays Shinji, who is co-habiting with Makoto (the wonderful Maki Murakami in her first lead role). Shinji wants them to marry, but Makoto wants to leave things as they are. This is the first sign of friction. When Shinji brings a dog to the flat, Makoto insists that he takes it to a dogs’ home. Shinji leaves with the dog, but never returns. We watch the change in Makoto. This is a slight story which gains its power from Murakami’s performance. Makoto’s final cry of pain seems over-extended, though it has been called audacious. My other niggle is that Kanyama adopts this year’s cliché, which is to start the film by previewing a later scene. It adds nothing to the drama.

In The Last Report on Anna (Márta Mészáros, Hungary, 2009), Péter (Ernõ Ferkete) is a young academic in 1970s Hungary. He is asked to persuade the dissident Anna (Enikö Eszeyi) to return home while he is at a conference in Brussels. Mészáros shows their developing relationship, which is complicated when Péter’s wife is allowed to join him and decides to stay in the West. This film complements The Lives of Others in showing an individual’s response to communism, though Péter is kept in line more by carrots than sticks. Mészáros offers a satisfying character study with political overtones.

Elsewhere (Frederic Pelle, France, 2010) opens with a croupier in a casino boasting of his plans for a long holiday in exotic places. A scam worthy of Melville seems in the offing, but Pelle takes us in another direction. Patrick (Nicholas Abraham) prepares for his journey of a lifetime, but preparations seem sufficient and he grows older without bothering to travel. Excitement comes into his life when he has an affair with a waitress from a Thai restaurant, an event which has unexpected consequences. This is an unassuming film about an unassuming man, which presents difficulties for its makers in holding an audience’s attention. Elsewhere takes its place alongside The Diary of a Country Priest (1950) and About Schmidt (2002) in meeting the challenge. It touches the Walter Mitty in us all: the journey never made, the garden which remains unplanted, or the book left unwritten. By its very understatement this film could slip under the radar, which would be a pity.

How I Ended This Summer (Aleksei Popogrebsky, Russia, 2010) deposits us on the edge of the Arctic Circle, where Sergei (Sergei Puskepalis) and the younger, bored Pavel (Grigoriy Dobrygin) man a remote weather station. When Sergei’s family is killed in an accident, Pavel delays passing on the news and eventually flees, fearing his colleague’s response. There is a slow build-up of tension and the oppressive grimness of the environment is well captured. The trouble is that Pavel’s reason for holding back the news and his extreme response to Sergei’s anger are hard to understand. If you are to enter into the lives of the characters, you have to believe in their motivations.

America and Canada produce a stream of well-made indie films which do well on the festival circuit, even if their commercial potential is less assured. In Fanny, Annie & Danny (Chris Brown, US, 2010), Fanny (Jill Pixley) has learning difficulties and loses her job and her place in a hostel. Her sister Annie (Carlye Pollack) is obsessed by her forthcoming wedding when she isn’t worrying about being ousted from her job, while her music promoter brother Danny (Jonathan Leveck) is in debt after some dubious business deals. This ill-assorted trio come together at their parents’ house, where their mother (Collette Keen) is intent on having a traditional Christmas while their father prefers to escape to his shed. You know things will go wrong. There’s plenty of black comedy along the way, though an early close-up gives away the ending. Aside from this blemish, Brown gives us drama pared down to its essentials and none the worse for that. What you cannot forget is the mother’s corncrake voice as she dragoons her family into having a good time. Who can blame them for wanting to escape?

A Marine Story (Ned Farr, US, 2010) was billed as having its world premiere at the festival, though it won an award at Outfest in Los Angeles. Alex (Dreya Weber) is honourably discharged from the marines and returns to her home town, where she has to fit in with a macho culture. She is asked to help a wayward teenager join the military as an alternative to going to prison. A bond forms between the two women, but when the reasons for Alex’s discharge become clear, her life becomes more complicated and more dangerous. Weber achieves a balance between Alex’s femininity and her need to prove herself in a masculine world. Unusually the female characters are fleshed out more than the men. Small town life can be dull, but Farr introduces enough incident to avoid dullness, but not so much that the action becomes melodramatic. This is a work which comments on a social issue without becoming didactic.

The Red Machine (Stephanie Argy and Alec Boehm, US, 2009) makes no pretence to be a profound film, but is a good one with echoes of The Counterfeiters (2007). It is 1935. Safe-cracker Eddie (Donal Thoms-Capello) is caught, but his salvation comes in the unlikely form of a naval lieutenant F. Ellis Coburn (Lee Perkins), who is as deadpan as Buster Keaton. Eddie is co-opted to steal details of an encryption device used by the Japanese, the red machine of the title. The film follows the intricacies of their task and its Machiavellian aftermath, but at its heart is the relationship between two men who appear so mismatched. The film looks impressive notwithstanding its small budget.

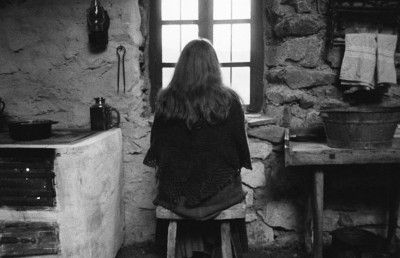

Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy was a favourite of mine at Bradford a few years ago. Her latest work is Meek’s Cutoff (US, 2010), set on the Oregon Trail of the 1840s. Reichardt makes a nod to B-movie Westerns by eschewing the widescreen format, but her approach to her subject is markedly different from that of old-time directors. Meek (Bruce Greenwood) guides a small band of settlers to a new land, but they become disillusioned with him as their water supply dwindles and there is no sign of their destination. They capture a native American and as Meek becomes increasingly at odds with the party, they put their faith in the prisoner to lead them to water. We never discover whether their faith is justified. This film looks impressive despite its limited budget. Admirers of Reichardt will be accustomed to the leisurely pace. Dialogue is sparse, but there is enough to hold the attention visually, with mundane tasks such as sewing taking on a sacramental quality. The most intriguing scenes show the settlers’ reaction to their prisoner. Their incomprehension as he speaks his own language is tangible. Meek wants to kill him, but the women are more sympathetic. When the prisoner scratches marks on rocks, Meek suspects him of leaving messages for his compatriots, but the God-fearing settlers intuit that the symbols have religious significance. The cast is impeccable, though as in A Marine Story the male settlers have fewer opportunities to show their individuality. The film recalls Malick’s The New World (2005) in its acceptance of nature’s dominance. You could read a lot into the story. Is it about environmental degradation? Are the settlers the Children of Israel? Does Meek represent Bush? Reichardt leaves that open. The film consolidates her reputation and deserves a wide showing.

Aaron Katz is another film-maker whose work has been screened at previous Bradford festivals. His third film is Cold Weather (US, 2010). Doug (Cris Lankenau) has moved to Portland and stays with his sister Gail (Trieste Kelly Dunn). When he meets his former girlfriend Rachel (Robyn Rikoon), he introduces her to Carlos (Raul Castillo), a budding DJ he works with at an ice-packing depot. Doug fancies himself as a detective and when Rachael disappears, he and Gail search for her after some prompting from Carlos. This is a thriller, but on a more domestic scale and with more humour than than In the Shadows et al. Katz relies more on plot than in his earlier work, but it is subordinate to the relationship before the four leads. This becomes apparent when the films ends abruptly with the plot only partly resolved. What we have seen is that the bond between brother and sister is reasserted. Portland is hardly photogenic, but Katz uses his regular cinematographer Andrew Reed to give the film a documentary feel and to make us look anew at the ordinary. The percussive score by Keegan DeWitt is atmospheric. Despite that abrupt finish, this is a more satisfying film than Point Blank, which ties up the loose ends. It is about real people.

Two films experiment by combining documentary techniques with feature film. Putty Hill (Matthew Porterfield, US, 2010) takes place after a suicide. Friends and family answer questions put by an unseen interviewer, the actors improvising their answers. You settle into the rhythm and the karaoke memorial service at the end makes an affecting finale when it would be easy to sneer at these people. The problem is that Porterfield seems determined to drown stretches of dialogue beneath a background of noise which includes not only music, but a car engine and a strimmer. This is mumblecore with a vengeance. The other film is Modra (Ingrid Veninger, Canada, 2010). Veninger took her daughter Hallie Switzer to meet her family in Modra, Slovakia, and used them as the cast for this teenage romance. Lina (Switzer) breaks up with her boyfriend before their holiday in Modra. On the spur of the moment she invites a classmate Leco (Alexander Gammal) to accompany her. They discover that they have little in common, but after emotional ups and downs they end the film in a good-natured friendship. The setting is unusual and the amateur leads give winning performances using improvised dialogue. There is a freshness about the enterprise which makes a familiar story come up newly minted. Not being one to waste an opportunity, Veninger photographed the audience at the festival for a scene which will be incorporated into her next film.

Which was to be my top film of the festival? I was torn between Meek’s Cutoff and The Last Report on Anna. Then came the final film on the final day which went to the top of my list. Based on real events, As If I’m Not There (Juanita Wilson, Ireland/Macedonia/Sweden, 2010) tells the story of ethnic cleansing in Bosnia and is adapted from the novel of the same name by the Croatian journalist Slavena Drakulic. Samira (Natasha Petrovic) leaves her home in Sarajevo to teach in a village school in Bosnia. There she is rounded up with the other villagers by Serbian soldiers. The men are shot and the woman interned, the younger ones including Samira being repeatedly raped by the soldiers. Samira asserts her identity by wearing make-up and by not hiding from her abusers, yet in doing this and by forming a relationship with the captain, she risks becoming alienated from the other women. Looking like a young Ingrid Bergman, Petrovic has little to say, but her face conveys her spectrum of emotions. This is a first feature for Petrovic and the director. It conveys the moral ambiguities of Samira’s position without shirking the violence or sensationalising the horrors. My niggles are some portentous and often unnecessary music, the uneven photography and that cliché of beginning with a preview of the ending. Generally I am wary of fictionalising real events: it becomes difficult to disentangle speculation and dramatic licence from fact, so that myths are perpetuated. By concentrating on the fate of one individual and not straying into political and religious issues, this film manages to address the inhumanity of war uncompromisingly.

Film as a Subversive Art: Amos Vogel and Cinema 16 (Paul Cronin, GB, 2003) was screened as a celebration of Vogel’s 90th birthday, According to historian Scott MacDonald. Vogel’s aims in setting up the New York film society Cinema 16 were to expand audiences and to show them other worlds. I am not sure that the Bradford festival achieved Vogel’s first aim: many Bradford residents seemed unaware that it was taking place. The largest attendances were for events involving celebrities such as Terry Gilliam and Timothy Spall, for films in English and for films in the Northern Showcase strand, where audiences often had a personal involvement in the filming. Subtitled films attracted a smaller but dedicated following. As to Vogel’s second aim, festivals provide a range of cinematic experiences, but this is of limited value unless the first aim is satisfied. How can we encourage cinema literacy? Perhaps we need more competitions, more film societies, more festivals or more foreign films on television. A few films achieve a limited release, which amounts to a short run in university cities. Others appear on DVD, but this can mean being made available in one region for a few months. A television screening gives wider exposure, but most subtitled films are scheduled for the dead hours. The potential of the Internet has yet to be fully exploited. Whichever medium is used, the problem remains the same: to create a demand for a film. For the film-maker, a festival screening offers exposure, publicity and, with luck, interest from a distributor. The depressing fact is that many of the films I have enjoyed at Bradford and Leeds over the years are destined to be little seen beyond the festival circuit. Once they have toured the festivals, they enter a state of limbo. A quick search of the Internet reveals that La Pivellina (2009), Fish Eyes (2009), Park Shanghai (2008), Modern Love Is Automatic (2009), Mermaid (2009) and Laundry (2002) are unavailable in Britain on DVD. Nor have they appeared on television. The Leeds Film Festival is hoping to screen films which proved popular at earlier festivals, but failed to find a distributor in Britain, La Pivellina being an example. This is a promising development. Film distribution remains sclerotic. Nor will new technologies bring about change so long as a handful companies maintain a stranglehold over film production and exhibition. The worldwide success of The King’s Speech might be a harbinger of things to come, but I would not bet on it.