16th Bradford International Film Festival

18-28 March 2010

Bradford has changed since my last visit two years ago. The city centre resembles a building site. Thread your way among the excavations and you reach the National Media Museum which is the hub of the film festival. This year’s event had also changed. What it lost in length, it gained in breadth: it was a week shorter, but satellite venues were used. Though any attempt to reach new audiences is to be applauded, this innovation caused frustration when the sole screening of a film was at a venue fifteen miles away. Nor were directions for reaching the venues included in the brochure. For all I know potential audience members are still wandering among the warehouses of Little Germany in the hope of finding the Bradford Playhouse

The Cinefile strand of films about the cinema always contains some gems. Reel Injun (Neil Diamond, Catherine Bainbridge and Jeremiah Hayes, US, 2009) examines how the American Indian has been portrayed on screen from the noble savage of the early days to the stereotypical enemy, a shift which occurred with the Depression of the 1930s. Rehabilitation had to wait for forty years until equal rights came on the agenda. Reel Injun yields offbeat facts – headbands were used by actors playing Indians to keep their wigs in place during action sequences – but the film’s chief interest lies in the opinions of American Indians who have become activists and film critics. You look at Westerns with new eyes.

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Inferno (Serge Bromberg and Ruxandra Medrea Annonier, France, 2009) follows Clouzot’s attempts in 1964 to write, produce and direct a tale of obsessional jealousy. After eighteen weeks on location and with no sign of a coherent film emerging, Clouzot had a heart attack and Columbia took the opportunity to close down the shoot. This is the cautionary tale of an auteur who tried to control everything and lost touch with reality. The surviving fragments reveal that Clouzot became obsessed with psychedelic imagery, which was fashionable at the time, but would have made the film look dated within a decade. This documentary seems more interesting that the film Clouzot never made.

Aside from Cinefile, Bradford has no distinct documentary strand and it is notable this year that fact and fiction can be difficult to disentangle. Three films have anthropological interest, the first being the documentary Constantin and Elena (Andrei Dascalescu, Romania, 2009), which received its UK premiere. The camera follows the director’s grandparents who live in rural Romania. We see them storing food for the winter and joining in the village celebrations. These activities seem timeless, yet change is coming: mobile phones are taken for granted, though Constantin has to grapple with a Pepsi can. The Orthodox Church holds sway in this world, while Elena is busy making rugs for the couple’s funerals (the only thing they agree on is that fifty-two rugs are not enough). My reservations are that some scenes seem played for the camera and there is a lack of dramatic shape: even a documentary should lead somewhere.

There is more humour in Home from Home (Sung Hyung Cho, Germany, 2009). South Korean girls migrated to Germany during the 1960s to work as nurses and some married Germans. We follow three such couples who retired to a ‘German village’ in Korea. The men negotiate the two cultures with tolerance and varying degrees of wholeheartedness. This is a sympathetic portrait of a community which the indigenous population treats as a tourist attraction, to the annoyance of residents. Sometimes we laugh at the men’s stereotyped German attitudes, but mostly we are on their side. The oldest man is a genuine character who connives with the camera. We are happy to follow him anywhere.

Fish Eyes (Wei Zhang, China/South Korea, 2009) is a debut feature which had its UK premiere. It is an austere piece with minimal dialogue and no music. In an isolated desert region an old man grows sunflowers, while his son shows more interest in joining the local motorcycle gang. Their life changes when the old man takes home a young woman he encounters while fishing. Accept the slow rhythm and the images become hypnotic. Part of the appeal as in many Chinese films lies in the presentation of a society so different from ours. It seems timeless, but intimations of change are there. Even the people who came expecting to see Fish Tank seemed won over.

Two documentaries focus on individuals. The Woman with the 5 Elephants (Vadim Jendreyko, Switzerland, 2009) has proved popular on the festival circuit, and was given its first UK screening. It profiles Swetlana Geier, an octogenarian academic who specialises in translating Dostoyevsky into German (his five mammoth novels are the five elephants referred to in the title). The film proves fascinating for three reasons. Firstly there is Geier’s eventful life. Born in the Ukraine, she worked for the Germans when her country was invaded and subsequently settled in Germany. Second, she attempts the difficult moral balancing act of distinguishing the German people whose culture she admires from the Nazi regime, while acknowledging what she gained from the latter. Third, she talks eloquently of the process of translation, which becomes a collaborative effort. Equally revealing is what she doesn’t say: there is little about life in Germany during the immediate post-war years and how she distanced herself from her collaboration with the Nazis. Despite this reticence, Geier wins you over.

Jendreyko’s work contrasts with Toto (Peter Schreiner, Austria, 2009), which follows Antonio Cotroneo from his home in Vienna to his birthplace in Calabria. Cotroneo is by no means as interesting or as articulate as Geier and overstays his welcome at 128mins. Profundity remains at the level of whether he prefers cannabis to cigarettes. It is possible to construct a hypnotic film around a life of quiet desperation, but Schreiner fails to achieve this. The consolation is some luminous black and white photography.

Park Shanghai

There comes a point for most people when we realise how far we have strayed from our youthful aspirations. This moment is captured in Park Shanghai (Kai Kevin Huang, China, 2008), which was selected for the festival by film-maker Ying Liang and was another debut work having a UK premiere. A high-school reunion takes place in a Shanghai hotel. The former friends are in their twenties. Earning a living has become a priority even for the poet. We are left to decide whether this represents an inevitable process of growing up or an abandonment of ideals. Park Shanghai is a low budget film which takes place almost in real time. It is shot on location, largely on the hotel roof, with the Shanghai skyline as a backdrop. Audiences who dislike heights might feel queasy. We discover the friends’ dreams and share their regret at relationships which never came to fruition. This is a young man’s film, which is a statement of fact rather than a criticism. It is intelligent, moving and well made – and deserves a wide showing.

In Greenberg (Noah Baumbach, US, 2010), Roger Greenberg (Ben Stiller) is having the same problem of accommodating to the realities of life, the difference being that he has reached middle age. After being discharged from a mental hospital, he looks after his brother’s house while the family are away. He strikes up a relationship with the family’s personal assistant, Florence (Greta Gerwig), but his erratic behaviour dooms this to failure. As a portrait of someone struggling with depression, this film has the ring of authenticity. Stiller and Gerwig give understated performances and we can appreciate the humour of Greenberg’s complaining letters to corporate bodies, even if Greenberg is unaware of it. As a bonus Gerwig sings a Judee Sill song and not many films offer you that. If you aren’t a Stiller fan, don’t let that deter you from seeing Greenberg.

Vortex

Family life is a fertile subject for film-makers. Vortex (Gytis Lukšas, Lithuania, 2009) is an adaptation of the 2003 novel by Romualdas Granauskas and was another UK premiere. This is the story of Juzik, from boyhood to finding work in a quarry. There he has an affair with Klara and marries her friend Maska, who urges him to leave her when she cannot give him a child. The Lithuanian selection panel for the foreign language Oscar described this as ‘the first telling of the story of how the Soviet times affected a human soul and body,’ but for me it is a personal tragedy with politics kept in the background. Shot in monochrome, this is a work of unremitting bleakness which could have been made in the Soviet era. It is long (142 minutes), but persevere and let the human drama unfold. It gains power as it goes along.

Donkey (Antonio Nuic, Croatia/Bosnia-Herzegovina/GB/Serbia, 2009), a UK premiere, also takes place in a specific political context, this time the end of the Balkan war, but like Vortex the drama is domestic. Boro takes his wife and son Luka on holiday to his childhood home in rural Herzegovina. His family still live there, including his brother who was paralysed on fleeing Sarajevo. Family tensions sour the holiday mood, while the donkey Luka befriends becomes the focus of family conflicts when it is sold. The breakup of Yugoslavia has cast a long shadow over Balkan cinema, though judging by Donkey this stage is coming to a close. This is a leisurely film which draws you into its world, though the bleached colour is disconcerting. Whether the donkey symbolises redemption as the programme notes suggest is another matter. The drama could stand without it.

Whip It (Drew Barrymore, US, 2009) was programmed as a crowd-pleaser to close the festival and is the third of this trio about families. Bliss (Ellen Page) becomes bored with life in small-town Texas. She has a pushy mum and a dad who is mad on football. Unknown to them she joins a team taking part in an all-female roller derby. This is a feel-good movie and Page (star of Juno) looks too fragile for the rough and tumble of competitive skating. Despite these reservations, this is a film which was enjoyed by the audience and is a promising debut for Barrymore as a director.

This was not a strong year for comedies judging by three which received their UK premieres at Bradford. Perrier’s Bounty (Ian Fitzgibbon, Ireland/GB, 2010) was the festival’s opening film. Michael (Cillian Murphy) crosses crime baron Perrier (Brendan Gleeson). Perrier sets out to exact his revenge, while the hapless Michael escapes accompanied by his neighbour (Jodie Whittaker) and his father (the most interesting character and a star turn by Jim Broadbent). The need for a narrator signals that all is not well in the script department. The dialogue is crisp and often funny, but this feels like a variation on In Bruges which was seen at Bradford a couple of years ago, also with Gleeson as the heavy. Wrapping up the plot takes priority over developing the characters and doesn’t make Perrier’s Bounty stand out from other Irish gangster films.

In Fluke (Keményffy Tamás, Hungary, 2008), an oil pipeline to Austria is tapped where it passes through a village and the residents take full advantage of the opportunity to make money. This film inhabits the anarchic world beloved of Emir Kusturica and looks back to Whisky Galore! There’s a lot going on, but as with Perrier’s Bounty we’ve been here before. More original is The Last Action (Michael Rogalski, Poland, 2009), which follows a group of veterans from the 1944 Warsaw Uprising who come out of retirement to work a scam on gangsters. It feels like an episode of a television series, but at least it’s fun.

There were two contrasting feminist films. Run Lola Run was a hit some years ago. A lesbian take on the same theme, And Then Came Lola (Ellen Seidler and Megan Siler, US, 2009), a UK premiere, is set in San Francisco. We follow photographer Lola on a dash across town with photographs for a client. Three scenarios for her journey are offered. This is a light-hearted film presenting a city populated almost entirely by gay characters. So far, so unusual. My qualm is that if this were a straight film, it would resemble the sexploitation movies of the seventies and hardly merit a screening. Should a lesbian film be judged by different criteria?

More to my taste was Modern Love is Automatic (Zach Clark, US, 2009). Bored, taciturn nurse Lorraine (Melodie Sisk) loses her boyfriend and takes a new flatmate, the ever-chattering Adrian (Maggie Ross) who assures her that they will be ‘the best flatmates ever’. Melodie develops a new pastime as a dominatrix, while Adrian’s nascent modelling career dwindles to a working in a mattress shop where scantily-clad assistants share the mattresses with male customers (a marketing concept yet to reach Bradford). Meanwhile Adrian’s boyfriend develops an obsession with Lorraine in a classic triangular relationship which leads to tragedy. The characters discover like those in Shanghai Park that real life never quite matches their ambitions. In Clark’s words, ‘It’s a movie about feeling stuck in a rut, and trying to get out of it, and finding yourself in a new rut.’ Characters who initially seem facile elicit our sympathy. This is an appealing and amusing film, deftly shaped by Zach Clark who edited Aaron Katz’s Dance Party, USA screened at Bradford three years ago.

Among films with a political theme were two sobering documentaries. Presumed Guilty (Roberto Hernández and Geoffrey Smith, Mexico 2008) is an attack on the Mexican legal system in which the defence has to argue against presumed guilt – assuming the case ever reaches court. It is an approach which ensures high conviction rates rather than justice. Though the flaws are obvious, the case being followed is overturned on appeal, suggesting that part of the problem lies in the system being overloaded and under-resourced, while the accused requires a tenacious defence team to break through bureaucratic inertia. We can criticise the police and judiciary. My qualm is that though the ideals of those behind the film are worthy, in a society contending with gangs and drugs, justice becomes arbitrary. Reforming the legal system alone is not enough and with a crackdown on terrorism, other countries are sleepwalking towards the Mexican model.

The Unworthy (Renate Gűenther-Greene, Germany, 2009), another UK premiere, offers an example of what happens when a political system becomes corrupt. Children in Nazi Germany could be taken from their parents because they were retarded, disruptive, or because they displayed a liking for proscribed music such as jazz. No justice here. Once the children were in concentration camps, they could be used as slave labour or killed at the whim of the authorities. Survivors tell their stories in this harrowing film which will provide (a) valuable source material for future historians, along with those meticulous and damning written records detailing the fate of every child.

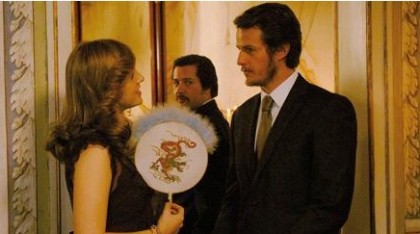

Based on a true story, L’Affaire Farewell (Christian Carion, France, 2009) follows a reluctant French go-between who passes on secrets from a disaffected KGB officer. This is a world of cross and double cross, where hidden microphones mean that conversations have to take place to the accompaniment of blaring music. Most takes on the Cold War are American or British, so a French perspective is refreshing. If anything it is the American characters who strike a false note. Emir Kusturica is better known as a director, but he proves his worth as an actor, revealing the complexity of the Russian officer’s position and his recklessness. This is an efficient spy drama which becomes nail-biting in its final stages.

No One Knows about Persian Cats (Bahman Ghobadi, Iran, 2009) is shot in semi-documentary style. An indie rock band from Tehran searches for new members and seeks permission to perform in London. They have to run the gauntlet of a repressive regime and corrupt officials, as well as contending with the silver tongue of their fixer who talks his way out of every situation and tries to turn it to his advantage. This should not be dismissed as a music film. It offers a portrait of life in Iran as seen through the eyes of young people and offers another example of contemporary values clashing with tradition. The consequences are tragic. Here is an engrossing film of great humanity which works as a political statement.

Vincere

Vincere (Marco Bellocchio, Italy/France, 2009) is the story of Ida Dalser, who claimed to be Mussolini’s first wife. Both Dalser and her son whom Mussolini might have fathered were incarcerated in mental hospitals. Whether Dalser’s claims were true is left open. The film has a sweep which makes it visually reminiscent of The Conformist and an operatic score. It can’t fail to overwhelm you. My reservations came later. Firstly, Filippo Timi looks nothing like Il Duce, which can be disconcerting when studio action morphs into archive clips and back again. Second, the film’s emphasis is on Mussolini’s rise to power, so that the Second World War and the revolt against him are treated cursorily. It might have been better to leave them out altogether as this part of the story is well known and both Dalser and her son were dead by then, so Mussolini’s fate does not affect their story. The most serious problem is that the sumptuousness can overwhelm the subject matter: the images stay in the mind rather than the inhumanity.

Eccentricities of a Blonde Haired Girl

Bellocchio is 70, but he is a stripling compared with Manoel de Oliveira who made Eccentricities of a Blonde Haired Girl (Portugal/Spain/France, 2009) when he was 100 (his first film dates from 1931). This is a work which fits into no particular category. Macario is an accountant in his father’s business. He becomes obsessed by a blonde living opposite his office, gets to know her and proposes to her. When his father objects to the marriage, Macario leaves the business and becomes penniless. Eventually his father relents and takes him back, but this is when Macario makes a discovery about the blonde which changes everything. The film aroused conflicting opinions at Bradford. Some people found it old fashioned and contrived; I liked its simplicity. There are echoes of Buñuel in the wry, elegant detachment with which bourgeois society is dissected, but de Oliveira is his own man. My only qualm is that the device of having the older Macario recounting the story to a stranger in a train seems unnecessary and contrived.

Aside from the opportunity to see new films which might not otherwise reach the big screen, festivals offer an opportunity to become reacquainted with old favourites and to discover films which were previously overlooked. A glory of the Bradford festival is its ability to attract distinguished guests whose appearances can be accompanied by retrospectives of their films. To launch a digital restoration of The Railway Children there was a reunion of those involved in making the film. Sadly its director Lionel Jeffries died a month earlier. Fernando Meirelles and Imelda Staunton were other guests who gave screentalks. Work commitments kept Nicholas Roeg away, but most of the films he directed were screened. John Hurt proved to be a popular guest. His filmography runs to 125 items, so not all are masterpieces and only a few could be shown at the festival. My pick was Shooting Dogs (Michael Caton-Jones, GB, 2005), which proved as powerful as ever.

Rita Tushingham introduced a screening of A Taste of Honey (Tony Richardson, GB, 1961), her first film. Background on the film came from Keith Withall, who led a discussion after the screening. More sessions like this would be welcome. Despite such advocacy, my reservations about the film remain. Walter Lassally’s photography captures Manchester of fifty years ago in forensic detail, but it overwhelms the domestic drama which has a far greater emotional impact on stage. And does black and white photography perpetuate the myth of the grim North? Social realism is as stylised as every other movement.

Bradford’s Media Museum houses an extensive television archive, with a selection of works being screened throughout the festival, albeit to tiny audiences. Two works made as strong an impression on me as anything in the festival. Looks and Smiles (ATV, 1981) is an early work of Ken Loach. This story of unemployed school leavers in Sheffield avoids the polemical edge which intrudes into some of his later work. Loach seems to me at his best in domestic dramas. Stronger than the Sun (Michael Apted, BBC, 1977) originally appeared in the ‘Play for Today’ series and features committed performances by Tom Bell and Francesca Annis as workers in a nuclear facility who want to publicise lax safety standards. These plays made me believe in a golden age of British television which has slipped away.

Short films have always been included in the Bradford programmes, despite the myriad of formats which cause headaches for the projectionists. I missed the finalists in the Shine short film competition, but a programme of international shorts proved a depressing experience. Conversely the short films preceding the features were stronger than usual. My favourites included Alienadas (Andrew Barchilon, Argentina/US, 2009). A collection of preserved human heads is discovered in a decaying mental hospital. This is an unpromising subject, but the film touches on the links between consciousness and neurobiology in a magical way. Hammered (Collette Chambers, GB, 2009) is a black comedy in which a burglar calls the police when he encounters more than he bargained for. Uerra (War) (Paulo Sassanelli, Italy, 2009) is set at the end of the Second World War and dramatises a neighbourhood brawl which is broken up by American military police. This is a sophisticated piece of film-making, bursting with energy. Scent (Darren Bolton, GB, 2009) is the tale of a pensioner who cannot accept that his wife is dead. It is a harrowing work which was omitted from the brochure. It deserves better.

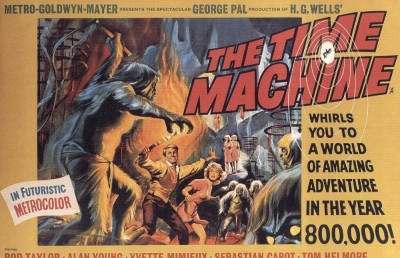

The widescreen weekend takes place during the festival. This popular event draws enthusiasts from around the world to glory in the joys of Cinerama, VistaVision, et al. From the viewpoint of a festival-goer this puts one screen out of action for two days, while widescreen devotees rarely sample the festival’s esoteric offerings. Is it time to separate the two events? As a consolation it provided me with the rare opportunity to see Woody Allen’s Manhattan on the big screen.

Bradford has a lot to live up to as the world’s first UNESCO City of Film. Taking the festival as a whole, the view of one regular festival-goer was that the new films were well crafted, but there was a dearth of outstanding works. This seems a fair summary, with a high standard of cinematography being noticeable – and often an absence of concision. The works which linger in my mind reveal an apparent simplicity: Eccentricities of a Blonde Haired Girl, No One Knows about Persian Cats, Modern Love is Automatic and Park Shanghai. None is likely to get a wide cinema release, which says something about my taste, the fossilised system of film distribution or the paucity of film education. Audience numbers were down this year. This may be a sign of economic stringency, but the perennial problem of how to boost audience numbers needs addressing if the festival is to thrive. There is a need to target particular groups. Bradford has a university, but few students were in evidence. Nor were members of the sizeable Polish community which was catered for in previous years. Given the large sector of the local population originating from the Indian subcontinent, the paucity of Asian faces in the audience (and on screen) was the most glaring omission. Sometimes being at the festival felt like being in a cultural bubble, cut off from the city lying on the other side of that building site. Bradford is changing, even if buying a meal on a Sunday still presents a challenge. The festival is innovating in its expansion into alternative venues and it presents a large number of UK premieres, but it cannot afford to rest on its laurels.